Cornell University

| |

| Latin: Universitas Cornelliana[1] | |

| Motto | “I would found an institution where any person can find instruction in any study”[2][3] |

|---|---|

| Type | Private[4] land-grant research university |

| Established | April 28, 1864 |

| Founder | |

| Accreditation | MSCHE |

Academic affiliations | |

| Endowment | $10.7 billion (2024)[5] |

| Budget | $5.4 billion (2023)[6] |

| President | Michael Kotlikoff |

| Provost | John Siliciano |

Academic staff | 1,639 in Ithaca, New York 1,235 in New York City 34 in Doha, Qatar |

| Students | 26,284 (fall 2023)[7] |

| Undergraduates | 16,071 (fall 2023)[7] |

| Postgraduates | 10,207 (fall 2023)[7] |

| Location | , , United States 42°27′13″N 76°28′26″W / 42.45361°N 76.47389°W |

| Campus | Small city[8], 745 acres (301 ha)[citation needed] |

| Other campuses[9] | |

| Newspaper | |

| Colors | Carnelian red and white[10] |

| Nickname | Big Red |

Sporting affiliations | |

| Mascot | Touchdown the Bear (unofficial)[11] |

| Website | cornell |

Cornell University is a private Ivy League land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York, United States. The university was founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White. Since its founding, Cornell has been a co-educational and nonsectarian institution. As of fall 2023, the student body included over 16,000 undergraduate and 10,000 graduate students from all 50 U.S. states and 130 countries.[7]

The university is organized into eight undergraduate colleges and seven graduate divisions on its main Ithaca campus.[12] Each college and academic division has near autonomy in defining its respective admission standards and academic curriculum. In addition to its primary campus in Ithaca, the university administers three satellite campuses, including two in New York City, the medical school and Cornell Tech, and one in Education City in Al Rayyan, Qatar.[12]

Cornell is one of three private land-grant universities in the United States.[a] Among the university's eight undergraduate colleges, four are state-supported statutory or contract colleges through the State University of New York system, including the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, the College of Human Ecology, the Industrial and Labor Relations School, and the Jeb E. Brooks School of Public Policy. Among Cornell's graduate schools, only the Veterinary Medicine College is supported by New York state. The main campus of Cornell University in Ithaca spans 745 acres (301 ha).

As of October 2024,[update] 64 Nobel laureates, 4 Turing Award winners, and 1 Fields Medalist have been affiliated with Cornell. Cornell counts more than 250,000 living alumni, which include 34 Marshall Scholars,[13] 33 Rhodes Scholars, 29 Truman Scholars, 63 Olympic Medalists, 10 current Fortune 500 CEOs, and 35 billionaires.[14][15][16][17][18]

History

[edit]19th century

[edit]Cornell University was founded on April 27, 1865, by Ezra Cornell, an entrepreneur and New York State Senator, and Andrew Dickson White, an educator and also a New York State Senator, after the New York State legislature authorized the university as the state's land grant institution.[19] Ezra Cornell offered his farm in Ithaca, New York as a preliminary site for the university, and granted $500,000 of his personal fortune as an initial endowment (equivalent to $12,373,000 in 2023) to the university. White agreed to be Cornell University's first president.

White spent the first three years at Cornell University overseeing construction of the university's first two buildings, and he traveled to recruit promising students and faculty.[20] On October 7, 1868, Cornell University was inaugurated, and 412 male students were enrolled the following day.[21]

Cornell developed as a technologically innovative institution, applying its academic research to its own campus and to outreach efforts. In 1883, it was one of the first university campuses to utilize electricity developed from a water-powered dynamo to light its campus.[22] Since 1894, Cornell has included colleges that are state-funded and fulfill state statutory requirements;[23] it has also administered research and extension activities that have been jointly funded by New York state and U.S. federal government matching funds.[24]

Beginning with its first classes, Cornell University has had active and engaged alumni. In 1872, the university became one of the first universities in the nation to include alumni-elected representatives on its board of trustees.[b]

Cornell University is home to Cornell University Press, founded in 1869. Cornell was first home to the Cornell Era, a weekly campus publication founded in 1868. In 1880, it was replaced with the founding of The Cornell Daily Sun, an independent student-run newspaper, which is now one of the nation's longest continuously published student newspapers in the nation.

From the 19th to early 20th centuries, Cornell had several literary societies that were founded to encourage writing, reading, and oration skills. The U.S. Bureau of Education described three of them as a "purely literary society" following the "traditions of the old literary societies of Eastern universities.

20th century

[edit]

In 1967, Cornell experienced a fire in the Residential Club dormitory that killed eight students and one professor. In the late 1960s, Cornell was among the Ivy League universities that experienced heightened student activism related to cultural issues, civil rights, and opposition to U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. In 1969, armed anti-Vietnam War protesters occupied Willard Straight Hall, an incident that led to a restructuring of the university's governance and forced the resignation of then Cornell president James Alfred Perkins.[28]

Since the 20th century, rankings of universities and colleges, Cornell University and its academic programs have routinely ranked among the best in the world. In 1995, the National Research Council ranked Cornell's Ph.D. programs as sixth-best in the nation. It also ranked the academic quality of 18 individual Cornell Ph.D. programs among the top ten in the nation, which included astrophysics (ninth-best), chemistry (sixth-best), civil engineering (sixth-best), comparative literature (sixth-best), computer science (fifth-best), ecology (fourth-best), electrical engineering (seventh-best), English (seventh-best), French (eighth-best), geosciences (tenth-best), German (third-best), linguistics (ninth-best), materials science (third-best), mechanical engineering (seventh-best), philosophy (ninth-best), physics (sixth-best), Spanish (eighth-best), and statistics/biostatistics (fourth-best). The council ranked Cornell's College of Arts and Humanities faculty as fifth-best in the nation, its Mathematics and Physical Sciences faculty as sixth-best, and its College of Engineering as fifth-best.[29][30]

21st century

[edit]

In 2000, Cornell began expanding its international programs. In 2004, the university opened Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar in Education City in Al Rayyan, Qatar.[31] The university also developed partnerships with academic institutions in India, the People's Republic of China, and Singapore.[32][33][34]

In August 2002, a graduate student group, At What Cost?, was formed at Cornell to oppose a graduate student unionization drive run by CASE/UAW, an affiliate of the United Auto Workers. The vote to unionize, held in October 2002, was rejected, and At What Cost? was considered instrumental in the unusually large 90% turnout for the vote and in the 2-to-1 defeat of the unionization proposal, the first instance in history in which a U.S. graduate school vote on unionization was defeated in a vote.[35][36][37]

In March 2004, Cornell and Stanford University laid the cornerstone for the building and operation of "Bridging the Rift Center", located on the border between Israel and Jordan, and used for education.[38] In 2005, Jeffrey S. Lehman, a former president of Cornell, described the university and its high international profile as a "transnational university".[39]

In 2017, Cornell opened Cornell Tech, a graduate campus and research center on Roosevelt Island in New York City, which won a competition bid initiated by former Mayor Michael Bloomberg, and is designed to spur technology entrepreneurship in New York City.

Campuses

[edit]Ithaca campus

[edit]

Cornell University's main campus is located in Ithaca, New York, on East Hill, offering views of the city and Cayuga Lake. The campus has expanded to approximately 745 acres (301 ha) since its founding, now including multiple academic buildings, laboratories, administrative facilities, athletic centers, auditoriums, museums, and residential areas.[40][41] In 2011, Travel + Leisure recognized Cornell's campus in Ithaca as one of the most beautiful in the United States, praising its unique blend of architectural styles, historic landmarks, and picturesque surroundings.[42]

The Ithaca campus is characterized by an irregular layout and a mix of architectural styles, which have developed over time and are attributed to the university's ever-changing master plans for the campus. The more ornate buildings generally predate World War II. Since then, more recent buildings on the campus are characterized by modernist architectural styles.[43]

Several Cornell University buildings have been named National Historic Landmarks,[44] and ten have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places: Andrew Dickson White House, Bailey Hall, Caldwell Hall, the Computing and Communications Center, Morrill Hall, Rice Hall, Fernow Hall, Wing Hall, Llenroc, and Deke House.[45] Three other listed historic buildings, the original Roberts Hall, East Robert Hall, and Stone Hall, were demolished in the 1980s to make way for new campus buildings and development.[46]

Central, North, and West campuses

[edit]The majority of Cornell University's academic and administrative facilities are located on its main campus in Ithaca. The architectural styles on the campus range from ornate Collegiate Gothic, Victorian, and Neoclassical buildings to more spare international and modernist structures. Frederick Law Olmsted, designer of Central Park, proposed a "grand terrace" overlooking Cayuga Lake in one of the earliest plans for the development of the campus.[47]

North Campus features primarily residential buildings, including ten residence halls designed to accommodate first and second-year students, and transfer students in the Townhouse Community.[48] The architectural styles of North Campus are more modern, reflecting the growth of the university and need for expanded student housing during the 20th century.

The West Campus House System showcases a blend of architectural styles, including Gothic-style buildings and residential halls collectively known as "the Gothics."[49]

In Collegetown, located near the campus in Ithaca, the architectural styles are diverse, reflecting the area's mixed-use nature. The Schwartz Performing Arts Center and two upper-level residence halls[50][51] are surrounded by a variety of apartment buildings, eateries, and businesses.[52]

Natural surroundings

[edit]Cornell University's main campus in Ithaca is located in the Finger Lakes region in upstate New York and features views of the city, Cayuga Lake, and surrounding valleys. The campus is bordered by two gorges, Fall Creek Gorge and Cascadilla Gorge. The gorges are popular swimming spots during warmer months, but their use is discouraged by the university and city code due to potential safety hazards.[53] Adjacent to the main campus, Cornell owns the 2,800-acre (1,100 ha) Cornell Botanic Gardens, which features various plants, trees, and ponds.[54]

Sustainability

[edit]Cornell University has implemented several green initiatives, designed to promote sustainability and reduce environmental impact, including a gas-fired combined heat and power facility,[55] an on-campus hydroelectric plant,[56] and a lake source cooling system.[57] In 2007, Cornell established a Center for a Sustainable Future[58] The same year, following a multiyear, cross-campus discussion about energy and sustainability, Cornell's Atkinson Center for Sustainability was established, funded by an $80 million gift from alumnus David R. Atkinson ('60) and his wife Patricia, the largest gift ever received by Cornell from an individual at the time. A subsequent $30 million commitment in 2021 will name a new multidisciplinary building on campus.[59]

As of 2020, the university, which has committed to achieving net carbon neutrality by 2035[60] is powered by six solar farms, which provide 28 megawatts of power.[61] Cornell is developing an enhanced geothermal system, known as Earth Source Heating, designed to meet campus heating needs.[62]

In 2023, Cornell was the first university in the nation to commit to Kyoto Protocol emission reductions.[63] The same year, a concert held at Barton Hall by Dead & Company raised $3.1 million for MusiCares and the Cornell 2030 Project, two organizations which have contributed to the establishment of the Climate Solutions Fund and aims to catalyze large-scale, impactful climate research across the university, which will be administered by the Atkinson Center.[64][65]

New York City campuses

[edit]Weill Cornell

[edit]

Cornell's medical campus in New York City, also called Weill Cornell, is on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. It is home to two Cornell divisions, Weill Cornell Medicine, the university's medical school, and Weill Cornell Graduate School of Medical Sciences. Since 1927, Weill Cornell has been affiliated with NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, one of the nation's largest hospitals.[66] While Cornell's medical school maintains its own faculty and academic divisions, it shares administrative and teaching hospital functions with Columbia University Medical Center.[67] In addition to NewYork-Presbyterian, Cornell's teaching hospitals include Payne Whitney Clinic in Manhattan and its Westchester Division in White Plains, New York.[68] Weill Cornell Medical College is affiliated with neighboring Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, one of the nation's leading cancer centers, Rockefeller University, and the Hospital for Special Surgery. Many faculty members have joint appointments at these institutions. Weill Cornell, Rockefeller, and Memorial Sloan–Kettering offer the Tri-Institutional MD–PhD Program, which is available to selected entering Cornell medical students.[69] From 1942 to 1979, the Weill Cornell Medical campus also housed the Cornell School of Nursing.[70]

Cornell Tech

[edit]

On December 19, 2011, Cornell and Technion – Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa won a competition for rights to claim free city land and $100 million in subsidies to build an engineering campus in New York City. The competition, established by former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, was designed to increase entrepreneurship and job growth in New York City's technology sector. The winning bid consisted of a 2.1 million square foot state-of-the-art tech campus to be built on Roosevelt Island, on the site of the former Coler Specialty Hospital. The following year, in fall 2012, instruction began at a temporary location at space donated by Google, located at 111 Eighth Avenue in Manhattan.[71] In 2014, construction began on the Cornell Tech campus, and the first phase was completed in September 2017. Thom Mayne of Morphosis Architects was selected to design Cornell Tech's first building.[72]

Other New York City programs

[edit]

In addition to the tech campus and medical center, Cornell maintains local offices in New York City for some of its service programs. The Cornell Urban Scholars Program encourages students to pursue public service careers, arranging assignments with organizations working with New York City's poorest children, families, and communities.[74] The College of Human Ecology and College of Agriculture and Life Sciences enable students to reach out to local communities by gardening and building with the Cornell Cooperative Extension.[75] Students om the School of Industrial and Labor Relations' Extension and Outreach Program make workplace expertise available to organizations, union members, policymakers, and working adults.[76] The College of Engineering's Operations Research Manhattan, located in the city's Financial District, brings together business optimization research and decision support services used in financial applications and public health logistics planning.[77] In 2015, the College of Architecture, Art, and Planning opened an 11,000 square foot, Gensler-designed facility at 26 Broadway in Manhattan's Financial District.[78] The General Electric Building at 570 Lexington Avenue serves as the New York City location for over a dozen additional Cornell University programs, including the New York City headquarters of the School of Industrial and Labor Relations and the New York City branch of the Cornell Cooperative Extension.[73]

Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar

[edit]In September 2004, Cornell opened the Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar in Education City, near Doha, which is the first U.S. medical school established outside of the United States. The college, which is a joint initiative with the Qatar government, is part of Cornell's efforts to increase its international influence.[31] The college, a full four-year MD program, mirrors the medical school curriculum taught at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City. The college also offers a two-year undergraduate pre-medical program, which has a separate admissions process and was established as an undergraduate program in September 2002 as the first coeducational institute of higher education in Qatar.[79]

The college is partially funded by the Qatar government through the Qatar Foundation, a Qatar state-led non-profit organization, which contributed $750 million for its construction.[80] The medical center is housed in a large two-story structure designed by Arata Isozaki, a Japanese architect.[81] In 2004, the Qatar Foundation, announced the construction of a 350-bed Specialty Teaching Hospital near the medical college in Education City, which was to be completed in a few years.[31]

Other facilities

[edit]Cornell University owns and operates a variety of off-campus research facilities and offers study abroad and scholarship programs.[82] These facilities and programs contribute to the university's research endeavors and provide students with unique learning opportunities.

Research facilities

[edit]

Cornell's off-campus research facilities include Shoals Marine Laboratory, a seasonal marine field station on Appledore Island off the Maine–New Hampshire coast, which is operated in conjunction with the University of New Hampshire and focuses on undergraduate education and research.[83] Until 2011, Cornell operated Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico, which was the site of the world's largest single-dish radio telescope.[84]

The university maintains several facilities dedicated to conservation and ecology, including the New York State Agricultural Experiment Station in Geneva, New York, which operates three substations, the Cornell Lake Erie Research and Extension Laboratory in Portland,[85] the Hudson Valley Laboratory in Highland,[86] and the Long Island Horticultural Research Laboratory in Riverhead on Long Island.[87] The Cornell Lab of Ornithology in Ithaca conducts research on biological diversity in birds.[88]

Additional research facilities include the Animal Science Teaching and Research Center, the Duck Research Laboratory, the Cornell Biological Field Station, the Freeville Organic Research Farm, the Homer C. Thompson Vegetable Research Farm, and biodiversity laboratories in Punta Cana in the Dominican Republic and the Peruvian Amazonia in Peru.[89][90][91][92][93][16]

Study abroad and scholarship programs

[edit]Cornell offers various study abroad and scholarship programs, which allow students to gain experience and earn credit towards their degrees. The "Capital Semester" program offers students the opportunity to intern in the New York State Legislature in Albany, the state capital. The Cornell in Washington program enables students to spend a semester in Washington, D.C., participating in research or internships.[94] The Cornell in Rome program allows students to study architecture, urban studies, and the arts in Rome, Italy.[95] The university is also a member of the Laidlaw Scholars program, which provides funding to undergraduates to conduct internationally focused research and foster leadership skills.[96]

Cooperative extension service

[edit]As New York state's land-grant university, Cornell operates a cooperative extension service, which includes 56 offices across the state. These offices provide programs in agriculture and food systems, children, youth and families, community and economic vitality, environment and natural resources, and nutrition and health.[97] The university operates New York's Animal Health Diagnostic Center, which conducts animal disease control and husbandry.[98]

Organization and administration

[edit]Cornell University is a nonprofit organization with a decentralized structure in which its 16 colleges, including 12 privately endowed colleges and four publicly supported statutory colleges, exercise significant autonomy to define and manage their respective academic programs, admissions, advising, and confer degrees. Cornell also operates eCornell, which provides online professional development and certificate programs[99] and participates in New York's land-grant, sea-grant, and space-grant programs.[100][101]

| Cornell University colleges and schools | |

|---|---|

| College or school | Year founded |

| Agriculture and Life Sciences | 1874 |

| Architecture, Art, and Planning | 1871 |

| Arts and Sciences | 1865 |

| Business | 1946 |

| Computing and Information Science | 2020 |

| Engineering | 1870 |

| Graduate School | 1909 |

| Hotel Administration | 1922 |

| Human Ecology | 1925 |

| Industrial and Labor Relations | 1945 |

| Law | 1887 |

| Medical Sciences | 1952 |

| Medicine | 1898 |

| Public Administration | 2021 |

| Tech | 2011 |

| Veterinary Medicine | 1894 |

Governance and administration

[edit]Cornell University is governed by a 64-member board of trustees, which includes both privately and publicly appointed trustees appointed by the Governor of New York, alumni-elected trustees, faculty-elected trustees, student-elected trustees,[102] and non-academic staff-elected trustees. The Governor, Temporary President of the Senate, Speaker of the Assembly, and president of the university serve in ex officio voting capacities. The board is responsible for electing a President to serve as the university's chief executive and educational officer.[103][104] From 2014 to 2022, Robert Harrison served as chairman of the board. He was succeeded by Kraig Kayser.[105] The Board of Trustees holds four regular meetings annually, which are subject to the New York State Open Meetings Law.[106]

On July 1, 2024, Michael Kotlikoff, who served as Cornell's 16th provost, began a two-year term as interim president,[107] succeeding Martha E. Pollack, Cornell's fourteenth president, who announced her retirement in May 2024.[108]

Colleges and academic structure

[edit]Cornell's colleges and schools offer a wide range of undergraduate, graduate, and professional programs, including seven undergraduate colleges and seven schools offering graduate and professional programs. All academic departments at Cornell are affiliated with at least one college. Several inter-school academic departments offer courses in more than one college. Students pursuing graduate degrees in these schools are enrolled in Cornell University Graduate School. The School of Continuing Education and Summer Sessions provides additional programs for college and high school students, professionals, and other adults.[109]

Cornell's four statutory colleges include the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, College of Human Ecology, School of Industrial and Labor Relations, and College of Veterinary Medicine. In the 2010-2011 fiscal year, these four colleges received $131.9 million in State University of New York (SUNY) appropriations to support teaching, research, and service missions, making them accountable to SUNY trustees and state agencies.[110][111][112] New York residents enrolled in these colleges qualify for discounted tuition; however, their academic activities are considered by New York state to be private and non-state entities.[113]:1

Cornell's nine privately endowed, non-statutory colleges include the College of Arts and Sciences, College of Architecture, Art, and Planning, College of Engineering, and College of Hotel Administration, each of which operate independently of state funding and oversight, which grants them greater autonomy in determining their academic programs, admissions, and advising. They also do not offer discounted tuition for New York residents.

As of 2023, among Cornell's 15,182 undergraduate students, 4,602 (30.3%) are affiliated with the College of Arts and Sciences, which is the largest college by enrollment, followed by 3,203 (21.1%) in Engineering, and 3,101 (20.4%) in Agriculture and Life Sciences. The smallest of the seven undergraduate colleges is Architecture, Art, and Planning, with 503 (3.3%) students.[7] Academic requirements for graduation are developed and managed by the respective colleges, and university-wide requirements for a baccalaureate degree include passing a swimming test, completing two physical education courses, and satisfying a writing requirement.

Fundraising and financial support

[edit]As of 2024, Cornell University has an endowment of $10.7 billion,[5] the 14th-largest among all U.S. universities and colleges. In 2018, Cornell ranked third among all U.S. universities behind Harvard University and Stanford University in private fundraising, collecting $743 million.[114] In addition to the university development program in Ithaca and New York City, each college and program has its own staffed fundraising programs. Cornell University has a robust fundraising program, and it has been the recipient of several sizable private donations, which have enabled the university to expand its reach, create new programs, and drive advancements in education and research.

In 1998, Weill Cornell Medicine was renamed in recognition of 1955 Cornell alumnus Sanford I. Weill, former chairman and CEO of Citibank, and his wife, following their $100 million donation to the university. As of 2013, the Weills have provided over $600 million in total donations to the university.[115]

In 2010, the Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future was established following an $80 million donation from David Atkinson and his wife, Patricia.[116]

In 2011, Chuck Feeney, a 1956 alumnus and founder of Hong Kong-based DFS Group, became the university's largest private donor in the university's history, giving $1 billion to the university to fund Cornell Tech, a technology-focused campus on Roosevelt Island in New York City, and other initiatives.[117]

In 2015, Joan and Irwin M. Jacobs, a 1956 alumnus and founder of Qualcomm, donated $133 million to fund the Jacobs Technion-Cornell Institute at Cornell Tech.[118]

In 2017, the university received a $150 million donation from Herbert Fisk Johnson III, an alumnus with five Cornell degrees and chairman and CEO of S. C. Johnson & Son, to create the Samuel Curtis Johnson Graduate School of Management, representing the second-largest gift in history to a business school.[119]

Academics

[edit]Cornell is a large and primarily residential research university, and a majority of its students are enrolled in undergraduate programs.[120] Since 1921, the university has been accredited by the Middle States Commission on Higher Education and its predecessor.[121] Cornell operates on a 4–1–4 academic calendar with the fall term beginning in late August and ending in early December, a three-week winter session in January, and the spring term beginning in late January and ending in early May.[122]

Along with Oregon State University, Pennsylvania State University, University of Georgia, and University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Cornell is one of only five U.S. land-grant universities that are also members of the other three grant programs, sea grant, space grant, and sun grant. Among the five, Cornell is the only private university to be members of all three grant programs.

Admissions

[edit]| Undergraduate admissions statistics | |

|---|---|

2022 entering class[123] | |

| Admit rate | 6.9% |

| Yield rate | 69% |

| Test scores middle 50% | |

| SAT EBRW | 700–760 |

| SAT Math | 750–800 |

| ACT Composite | 33–35 |

| High school GPA[i] | |

| Top 10% | 83.7% |

| Top 25% | 97.7% |

| Top 50% | 99.9% |

| |

Admission to Cornell University is highly competitive. In fall 2022, Cornell's undergraduate programs for its Class of 2026 included 71,164 applications from which only 5,168, or 6.9% applicants, were accepted.[124] For enrolling freshmen, the middle 50% range of SAT scores were 700–760 for evidence-based reading and writing and 750–800 for mathematics, and the middle 50% range of the ACT composite score was 33–35.[123]

The university attract a diverse and inclusive student body. In 2022, the proportion of admitted students who self-identify as underrepresented minorities increased to 34.2%, up from 33.7% in 2021, and 59.3% self-identify as students of color, an increase from 52.5% in 2017 and 57.2% in 2020. Among the 5,168 admitted in 2022, 1,163 were first-generation college students, up from 844 in 2020.[125] The university practices need-blind admission for U.S. applicants.[126]

Financial aid

[edit]

Cornell University, under Section 9 of its original charter, ensures equal access to education by admitting students without distinction based on rank, class, occupation, or locality.[127] The charter also mandates free instruction for one student from each Assembly district in New York state.[127]

From the 1950s to the 1980s, Cornell collaborated with other Ivy League institutions to establish a uniform financial aid system.[128] Although a 1989 consent decree ended this collaboration due to an antitrust investigation, all Ivy League schools still offer need-based financial aid without athletic scholarships.[129] In December 2010, Cornell pledged to match any grant component of financial aid offers from the seven other Ivy League schools and MIT and Stanford for accepted applicants considering these institutions.[130]

In 2008, Cornell introduced a financial aid initiative, which incrementally replaced need-based loans with scholarships for undergraduate students from lower-income families.[131] Despite a 27% drop in the university's endowment in 2008, attributable partly to the 2007–2008 financial crisis, Cornell president David J. Skorton allocated additional funds to continue the initiative, and sought to raise $125 million in donations for its support.[132] Two years later, in 2010, Cornell was able to successfully meet the full financial aid needs of 40% of full-time freshmen with financial need. The average undergraduate student debt upon graduation, as of 2010, was $21,549.[133]

International programs

[edit]

Cornell University is actively involved in fostering international cooperation and engagement through various academic programs, research collaborations, and global partnerships. The university is a member of United Nations Academic Impact, aligns itself with United Nations' goals, and promotes international collaboration among institutions of higher education.

Academic programs and study abroad opportunities

[edit]

Cornell offers a wide range of undergraduate majors with an international focus, including African Studies, Asian-Pacific American Studies, French Studies, German Studies, Jewish Studies, Latino Studies, Near Eastern Studies, Romance Studies, and Russian Literature.[16] Students have the opportunity to study abroad on any of the six continents through various programs.[134]

The Asian Studies major, the Southeast Asia Program, and the China and Asia-Pacific Studies (CAPS) major provide opportunities for students and researchers focusing on Asia. Cornell has an agreement with Peking University, which allows CAPS students to spend a semester in Beijing.[135] The College of Engineering exchanges faculty and graduate students with Tsinghua University in Beijing, and the School of Hotel Administration has a joint master's program with Nanyang Technological University in Singapore.

In the Middle East, Cornell's efforts are centered on biology and medicine. The Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar trains new doctors to improve health services in the region.[136] The university is also involved in developing the Bridging the Rift Center, a "Library of Life", a database of all living systems, based on the Israel-Jordan forder, in collaboration with those two countries and Stanford University.[137]

The university has agreements with several institutions around the world for student and faculty exchange programs, including Bocconi University, the University of Warwick, Japan's National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences,[138] the University of the Philippines Los Baños,[139] and the Indian Council of Agricultural Research.[140]

Joint degree programs

[edit]Cornell offers several joint degree programs with international universities. The university is the only U.S. member school of the Global Alliance in Management Education, and its Master's in International Management program offers the Global Alliance's Master's in International Management (CEMS MIM) as a double degree option, which enables students to study at one of 34 Global Alliance partner universities. Cornell has partnered with Queen's University in Ontario to offer a joint Executive MBA program,[141] which affords its graduates MBA degrees from both universities. Cornell also offers an international consulting course in association with the Indian Institute of Management Bangalore.[142]

Rankings

[edit]| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Forbes[143] | 10 |

| U.S. News & World Report[144] | 11 (tie) |

| Washington Monthly[145] | 8 |

| WSJ/College Pulse[146] | 27 |

| Global | |

| QS[147] | 16 |

| THE[148] | 20 |

| U.S. News & World Report[149] | 19 (tie) |

Cornell University has been routinely ranked among the top academic institutions in the nation and world by independent academic ranking asssessments. In 2024, Cornell was ranked 10th-best in the U.S. and 12th-best in the world by QS World University Rankings and 20th-best in the world by Times Higher Education World University Rankings.[150][151] The university has garnered praise for its contributions to research, community service, social mobility, and sustainability, evidenced by its placement in The Washington Monthly and The Princeton Review's rankings.[152]

In its annual edition of "America's Best Architecture & Design Schools," the journal Design Intelligence ranked Cornell's Bachelor of Architecture program best in the nation for most of the 21st century, including from 2000 to 2002, 2005 to 2007, 2009 to 2013, and 2015 to 2016. In its 2011 survey, the program ranked first and the Master of Architecture program ranked sixth-best in the nation.[153] In 2017, Design Intelligence ranked Cornell's Master of Landscape Architecture program fourth-best in the nation and its Bachelor of Science in Landscape Architecture program fifth-best nationally.[154][155]

Among business schools in the U.S., Forbes ranked Cornell's Johnson School of Management the ninth-best business school in the nation in 2019.[156] In 2020, The Washington Post ranked the School of Management eighth-best for salary potential, and Poets and Quants ranked it the 13th-best business school in the nation,[157] fourth-best in the nation for investment banking,[158] and sixth-best globally for salary.[159] The Johnson School of Management was ranked 11th-best nationally by Bloomberg Businessweek in 2019,[160] and 11th-best nationally and 14th-best globally by The Economist.[161] In 2013, the Johnson school was ranked second-best for sustainability by Bloomberg Businessweek.[162]

Cornell's international relations program is ranked among the best in the world by Foreign Policy magazine's Inside the Ivory Tower survey, which ranked Cornell's undergraduate program 12th-best in the world and its doctorate program 11th-best in the world in 2012.[163][164] In 2015, Cornell was ranked third-best among all New York colleges and universities for professor salaries.[165]

Library

[edit]

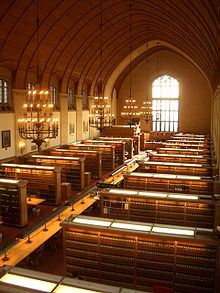

As of 2020, Cornell University Library, with over 10 million holdings, is the 13th-largest academic library in the United States.[166] As of 2005, the library is organized into 20 divisions, which hold 7.5 million printed volumes in open stacks, 8.2 million microfilms and microfiches, a total of 440,000 maps, motion pictures, DVDs, sound recordings, and computer files in its collections, and extensive digital resources and the University Archives.[167] It was the first among all U.S. colleges and universities to allow undergraduates to borrow books from its libraries.[16] In 2006, The Princeton Review ranked it the 11th-best college library.[168] Three years later, in 2009, it climbed to sixth-best.[169] The library plays an active role in furthering online archiving of scientific and historical documents. arXiv, an e-print archive created at Los Alamos National Laboratory by Paul Ginsparg, is operated and primarily funded by Cornell as part of the library's services. The archive has changed the way many physicists and mathematicians communicate, making the e-print a viable and popular means of announcing new research.[170]

Cornell University Press

[edit]Cornell University Press, established in 1869 but inactive from 1884 to 1930, was the first university publishing enterprise in the United States.[171][172] As of 2024, it is one of the country's largest university presses,[16] publishing approximately 150 nonfiction titles annually in various disciplines, including anthropology, Asian studies, biological sciences, classics, history, industrial relations, literary criticism and theory, natural history, politics and international relations, veterinary science, and women's studies.[172][173]

Academic publications

[edit]Cornell's academic units and student groups publish multiple scholarly journals, including at least five faculty-led and seven student-led academic publications. Faculty-led publications include the Johnson School's Administrative Science Quarterly,[174] the ILR School's Industrial and Labor Relations Review, the Arts and Sciences Philosophy Department's The Philosophical Review, the College of Architecture, Art, and Planning's Journal of Architecture, and the Law School's Journal of Empirical Legal Studies.[175] Student-led scholarly publications include Cornell Law Review, the Cornell Institute for Public Affairs' Cornell Policy Review, the Cornell International Law Journal, the Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy, and Cornell International Affairs Review. Physical Review, recognized internationally as one of the best and well known journals of physics, was founded at Cornell in 1893 before later being managed by the American Physical Society.

Research

[edit]

Cornell University is a prominent research institution, classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity."[176] The National Science Foundation ranked Cornell 14th among American universities for research and development expenditures in 2021 with $1.18 billion.[177][178] The Department of Health and Human Services and the National Science Foundation are the primary federal investors, accounting for 49.6% and 24.4% of all federal investments, respectively.[179] Cornell is ranked fourth in the world for producing graduates who pursue PhDs in engineering or natural sciences at American institutions and fifth for graduates pursuing PhDs in any field.[180]

Science, technology, and engineering research

[edit]Cornell has a rich history of scientific, technological, and engineering research accomplishments. The university has made significant contributions to the fields of nuclear physics, high-energy physics, space exploration, automotive safety, and computing technology, among others. Cornell consistently ranks among the top U.S. universities for patent acquisition and start-up company formation.[181] In the 2004–05 academic year, the university filed 203 U.S. patent applications, completed 77 commercial license agreements, and distributed royalties of more than $4.1 million to Cornell units and inventors.[16] In 2009 Cornell spent $671 million on science and engineering research and development, the 16th highest in the United States.[182]

Cornell has been involved in uncrewed missions to Mars since 1962[183] and played a vital role in the Mars Exploration Rover Mission in the 21st century.[184] The university's researchers discovered the rings around the planet Uranus[185] and operated the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico until 2011. This observatory housed the world's largest single-dish radio telescope at the time.[186]

The Automotive Crash Injury Research Center, founded in 1952, was a pioneering effort in crash testing and significantly improved vehicle safety standards.[187] It was the first to use corpses instead of dummies for testing, leading to crucial findings about the effectiveness of seat belts, energy-absorbing steering wheels, padded dashboards, and improved door locks.[187]

Cornell has long been at the forefront of advancements in computing technology. In the 1980s, the university deployed the first IBM 3090-400VF and coupled two IBM 3090-600E systems to investigate coarse-grained parallel computing. As part of the National Science Foundation's initiative to establish new supercomputer centers, the Cornell University Center for Advanced Computing was founded. Cornell has continued to innovate in this area, most recently deploying Red Cloud, a cloud computing service designed specifically for research. The Red Cloud service is now part of the NSF's Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE) supercomputing program.[188]

In the realm of high-energy physics, Cornell scientists have been researching fundamental particles for over 75 years. The university has played an integral role in the foundations of nuclear physics, with faculty members Hans Bethe and others participating in the Manhattan Project. In the 1930s, Cornell built the second cyclotron in the United States and, in the 1950s, became the first to study synchrotron radiation. The Cornell Electron Storage Ring, located beneath Alumni Field, was once the world's highest-luminosity electron-positron collider.[189][190] Cornell's accelerator and high-energy physics groups are involved in the design of the proposed International Linear Collider, which will complement the Large Hadron Collider and shed light on questions related to dark matter and the existence of extra dimensions.[191]

Philosophical research

[edit]The Sage School of Philosophy at Cornell University was founded in 1891 with philanthropic support from Henry W. Sage, a prominent figure in the lumber industry. In 1891, Sage endowed the establishment of the Sage School.[192] The school's namesake, Susan Linn Sage, died in 1885 in a carriage accident on Slaterville Road. Henry W. Sage, who was President of Cornell's Board of Trustees since 1875, sought to honor his late wife's memory through the establishment of the Sage School. In addition to the school's founding, Sage bestowed the title of Susan Linn Sage Professor of Christian Ethics and Mental Philosophy upon then Cornell president Jacob Gould Schurman.[192]

A cornerstone of the Sage School's early endeavors was the founding of The Philosophical Review in 1891, which was the first genuine philosophical review in the United States and has since been continuously published by the Sage School since its inception.

The Sage School of Philosophy's faculty has included several prominent philosophy scholars:

- Max Black, a leading figure in analytic philosophy, made significant contributions during his tenure at Cornell, where he remained from 1946 to 1977.

- Edwin A. Burtt, as the Susan Linn Sage Professor, challenged prevailing positivist and scientific views with his book, The Metaphysical Foundations of Modern Physical Science, published in 1924.

- Norman Malcolm, known for his engagement with Ludwig Wittgenstein's later thought, left a lasting impact on philosophy of mind, free will, determinism, and philosophy of religion during his time at the Sage School from 1947 to 1978.

- John Rawls, widely regarded as one of the greatest American political philosophers, spent a year of his graduate studies at the Sage School prior to joining the department as faculty, where he served from 1953 to the early 1960s.

- George Holland Sabine, known for his seminal work A History of Political Theory, published in 1937, provided a comprehensive account of political theory from ancient times to the rise of Nazism and fascism.

- Gregory Vlastos, a distinguished scholar, joined Cornell in 1948 as the Susan Linn Sage Professor of Philosophy. His work synthesized ancient philosophy and analytic philosophy, marking a decisive change to the study of Greek philosophy in the English-speaking world.

In a 2024 ranking published by the Philosophical Gourmet, Sage School is ranked among the best programs at 19, and top five in the world in the fields of value theory,[193] that is their focus on moral psychology, metaethics, applied ethics, philosophy of law, social philosophy and history of philosophy[194] ranging from ancient philosophy to modern philosophy. As of 2024, Sage School is home to several notable philosophers, including Tad Brennan, John Doris, Rachana Kamtekar, Kate Manne, Julia Markovits, Andrei Marmor, Shaun Nichols, Derk Pereboom, and others.

Student life

[edit]| Race and ethnicity[195] | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 35% | ||

| Asian | 21% | ||

| Hispanic | 15% | ||

| Other[c] | 13% | ||

| Foreign national | 10% | ||

| Black | 7% | ||

| Economic diversity | |||

| Low-income[d] | 16% | ||

| Affluent[e] | 84% | ||

Activities

[edit]

As of the 2016–2017 academic year, Cornell had over 1,000 registered student organizations. These clubs and organizations run the gamut from kayaking to full-armor jousting, from varsity and club sports and a cappella groups to improvisational theatre, from political clubs and publications to chess and video game clubs.[196] The Cornell International Affairs Society sends over 100 Cornellians to collegiate Model United Nations conferences across North America and hosts the Cornell Model United Nations Conference each spring for over 500 high school students. The Cornell University Mock Trial Association regularly sends teams to the national championship and is ranked fifth in the nation.[197] The Cornell International Affairs Society's traveling Model United Nations team was ranked 16th in the nation as of 2010.[198] Cornell United Religious Work is a collaboration among many diverse religious traditions, helping to provide spiritual resources throughout a student's time at college. The Cornell Catholic Community is the largest Catholic student organization on campus. Student organizations also include a myriad of groups including a symphony orchestra,[199] concert bands,[200] formal and informal choral groups,[201] including the Glee Club, the Chordials[202] and other musical groups that play everything from classical, jazz, to ethnic styles in addition to the Big Red Marching Band, which performs regularly at football games and other campus events.[203]

Organized in 1868, the oldest Cornell student organization is the Cornell University Glee Club.[204] Cornell also has an active outdoor community, including Cornell Outdoor Education and Outdoor Odyssey, a student-run group that runs pre-orientation trips for first-year and transfer students. A Cornell student organization, The Cornell Astronomical Society, runs public observing nights every Friday evening at the Fuertes Observatory. The university is home to the Telluride House, an intellectual residential society. The university is also home to three secret honor societies, Sphinx Head,[205] Der Hexenkreis, and Quill and Dagger[206][207] that have maintained a campus presence for over 120 years.

Cornell's clubs are primarily subsidized financially by the Student Assembly and the Graduate and Professional Student Assembly, two student-run organizations with a collective budget of $3.0 million per year.[208][209] The assemblies also finance other student life programs including a concert commission and an on-campus theater.

Greek life, professional, and honor societies

[edit]Cornell hosts a large[210][211][212][213][214] fraternity and sorority system, with 70 chapters involving 33% of male and 24% of female undergraduates.[215][216][217] Cornell's Greek Life has an extensive history on the campus with the first fraternity, Zeta Psi, being chartered by the end of the university's first year.[218] Alpha Phi Alpha, the first intercollegiate Greek organization established for African Americans, was founded at Cornell in 1906.[219][220] Alpha Zeta fraternity, the first Greek-lettered organization established for Latin Americans in the United States, was also founded at Cornell on January 1, 1890. Alpha Zeta served the wealthy international Latin American students that came to the United States to study. This organization led a movement of fraternities that catered to international Latin American students that was active from 1890 to 1975.[221] On 19 February 1982, La Unidad Latina, Lambda Upsilon Lambda fraternity was established;[222] it would eventually become the only Latino based fraternity in the nation with chapters at every Ivy League institution.[223] Latinas Promoviendo Comunidad/Lambda Pi Chi sorority was established on 16 April 1988, making the organization the first Latina-Based, and not Latina-exclusive, sorority founded at an ivy-league institution.[224]

Cornell's connection to national Greek life is strong and longstanding. Many chapters are among the oldest of their respective national organizations, as evidenced by the proliferation of Alpha-series chapters. The chapter house of Alpha Delta Phi constructed in 1877 is believed to be the first house built in America solely for fraternity use, and the chapter's current home was designed by John Russell Pope.[225] Philanthropy opportunities are used to encourage community relations, for example, during the 2004–05 academic year, the Greek system contributed 21,668 community service and advocacy hours and raised $176,547 in charitable contributions from its philanthropic efforts.[216] Generally, discipline is managed internally by the inter-Greek governing boards. As with all student, faculty or staff misconduct, more serious cases are reviewed by the Judicial Administrator, who administers Cornell's justice system.[216]

Press and radio

[edit]The Cornell student body produces several works by way of print and radio. Student-run newspapers include The Cornell Daily Sun, an independent daily, and The Cornell Review, a conservative newspaper published fortnightly.

Other press outlets include The Cornell Lunatic, a campus humor magazine, the Cornell Chronicle, the university's newspaper of record, and Kitsch Magazine, a feature magazine co-published with Ithaca College. The Cornellian is an independent student organization that organizes, arranges, produces, edits, and publishes the yearbook of the same name; it is composed of artistic photos of the campus, student life, and athletics, and the standard senior portraits. It carries the Silver Crown Award for Journalism and a Benjamin Franklin Award for Print Design, the only Ivy League yearbook with such a distinction.[226] Cornellians are represented over the radio waves on WVBR-FM, an independent commercial FM radio station owned and operated by Cornell students. Other student groups also operate internet streaming audio sites.[227]

Housing

[edit]

University housing is broadly divided into three sections: North Campus, West Campus, and Collegetown. Beginning in 1971, Cornell began experiments with co-ed dormitories and continued the tradition of residential advisors (RAs) within the campus system. Beginning in the 1990s, new students were largely assigned to the historic Baker and Boldt Hall complexes on West Campus. Since a 1997 residential initiative, West Campus houses transfer and returning students, and North Campus is mostly populated by freshmen, sophomores, and sorority and fraternity houses.[228] Prior to 2022, North Campus residents were overwhelmingly freshman, but the completion of the North Campus Residential Expansion provided housing for 800 sophomores in Toni Morrison Hall and Ganędagǫ Hall.[229]

Options for living on North Campus for upperclassmen include program houses and co-op houses. Program houses include Risley Residential College, Just About Music, the Ecology House, Holland International Living Center, the Multicultural Living Learning Unit, the Latino Living Center, Akwe:kon, and Ujamaa. The co-op houses on North are The Prospect of Whitby, Triphammer Cooperative, Wait Avenue Cooperative, Wari Cooperative, and Wait Terrace.[230] On West Campus, there are three university-affiliated cooperatives, 660 Stewart Cooperative, Von Cramm Hall, Watermargin, and one independent cooperative, Cayuga Lodge. In an attempt to create a sense of community and an atmosphere of education outside the classroom and continue Andrew Dickson White's vision, a $250 million reconstruction of West Campus created residential colleges there for undergraduates.[231] The idea of building a house system can be attributed in part to the success of Risley Residential College, the oldest continually operating residential college at Cornell.[232] In 2018, Cornell announced its North Campus Residential Expansion project, which was completed in Fall 2022. The university added 2,000 beds on North Campus through five new dorms and a dining hall. Ruth Bader Ginsburg Hall, Hu Shih Hall, and Barbara McClintock Hall are located on the east end of North Campus and are exclusively for freshmen. Sophomores have the option to live in Toni Morrison Hall or Ganędagǫ Hall, which are located on the west end of North Campus.[233]

Schuyler House, which was formerly a part of Sage Infirmary,[234] has a dorm layout. Maplewood Apartments, Hasbrouck Apartments, and Thurston Court Apartments are apartment-style, some even allowing for family living. Off campus, many single-family houses in the East Hill neighborhoods adjacent to the university have been converted to apartments. Private developers have also built several multi-story apartment complexes in the Collegetown neighborhood. Nine percent of undergraduate students reside in fraternity and sorority houses, although first semester freshmen are not permitted to join them.[235] Cornell's Greek system has 67 chapters and over 54 Greek residences that house approximately 1,500 students. About 42% of Greek members live in their houses.[236] Housing cooperatives or other independent living units exist, including Telluride House, the Center for Jewish Living, Phillips House (located on North Campus, 1975 all women; 2016, all men), and Center for World Community (international community, off campus, formed by Annabel Taylor Hall, 1972, mixed gender).[237] The cooperative houses on North include The Prospect of Whitby, Triphammer Cooperative, Wait Avenue Cooperative, Wari Cooperative, and Wait Terrace.[230] There also are cooperative housing options not owned by Cornell, including Gamma Alpha and Stewart Little.

As of 2023[update], Cornell's dining system was ranked second in the nation by The Princeton Review.[238] The university has 29 on-campus dining locations, including 10 "All You Care to Eat" cafeterias.[239] North Campus is home to three of these dining halls: Morrison Dining by Morrison Hall, North Star Dining Room in the Appel Commons, and Risley Dining in Risley Hall.[239] West Campus houses 6 dining halls, 5 of which accompany the West Campus residential houses: Cook House Dining Room, Becker House Dining Room, Rose House Dining Room, Jansen's Dining Room at Hans Bethe House, and Keeton House Dining Room.[239] Also located on West Campus is 104West!, a kosher/multicultural dining room.[239] Central Campus has Okenshields, a dining hall in Willard Straight Hall.[239]

Athletics

[edit]

Cornell University's 35 varsity intercollegiate athletic teams are known as the Cornell Big Red.[240] Cornell is an NCAA Division I institution and competes as a member of the Ivy League and the Eastern College Athletic Conference (ECAC), the largest athletic conference in North America.[241] Cornell's varsity athletic teams consistently challenge for NCAA Division I titles in a number of sports, including men's wrestling, men's lacrosse, men's ice hockey, and rowing. As an Ivy League member, Cornell is prohibited from offering athletic scholarships.[242]

Cornell's football team had at least a share of the national championship four times before 1940[243][244] and has won the Ivy League championship three times, last in 1990.[245]

In 2010, the men's basketball team appeared for the first time in the NCAA tournament's East Regional semifinals, known as the "Sweet 16." Cornell was the first Ivy League basketball team to make the semifinals since 1979.[246]

Cornell Outdoor Education

[edit]Cornell runs one of the largest collegiate outdoor education programs in the country, serving over 20,000 people every year. The program runs over 130 different courses including but not limited to: Backpacking and Camping, Mountain Biking, Bike Touring, Caving, Hiking, Rock and Ice Climbing, Wilderness First Aid, and tree climbing.[247] COE also oversees one of the largest student-run pre-freshman summer programs, known as Outdoor Odyssey.[248] Most classes are often entirely taught by paid student instructors and courses count toward Cornell's physical education graduation requirement.[249]

Cornell Outdoor Education includes the Lindseth Climbing Wall, which was renovated in 2016 and now includes 8,000 square feet of climbing surface up from 4,800 square feet previously.[250]

Cornelliana

[edit]

Cornelliana is a term for Cornell's traditions, legends, and lore. Cornellian traditions include Slope Day, a celebration held on the last day of classes of the spring semester, and Dragon Day, which includes the parading of a dragon built by architecture students. Dragon Day is one of the school's oldest traditions and has been celebrated annually since 1901, historically on or near St. Patrick's Day. The dragon is built by the first-year architecture students in the week preceding the start of Spring Break. Taunting messages are left for the engineering students during the week leading into Dragon Day, with pranks, a "nerd walk," and even "green streak" (in which the students paint themselves green) often targeting engineers and their classes. On Dragon Day, the dragon is paraded around central campus by the first-year students, starting behind Rand Hall and moving through Cornell until eventually returning towards the Arts Quad. During the parade, the upper-year architecture students walk behind the dragon in various costumes, typically constructed by themselves for the event. Throughout much of its history, the dragon was then set afire upon its arrival to the arts quad, but that has since been discontinued due to environmental regulations.[251][252][253]

According to legend, if a virgin crosses the Arts Quad at midnight, the statues of Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White will walk off their pedestals, meet in the center of the Quad, and shake hands, congratulating themselves on the chastity of students. There is also another myth that if a couple crosses the suspension bridge on North Campus, and the young woman does not accept a kiss from her partner, the bridge will fall. If the kiss is accepted, the couple is assured a long future together.[254]

The university is also host to various student pranks. On at least two different occasions, the university has awoken to find something odd atop the 173-foot (52.7 m) tall McGraw clock tower, once a 60-pound (27 kg) pumpkin and another time a disco ball. Because there is no access to the spire atop the tower, how the items were put in place remains a mystery.[255] The colors of the lights on McGraw tower change to orange for Halloween and green for St. Patrick's Day.[256] The clock tower also plays music.

The school colors are carnelian (a shade of red) and white, a play on "Cornellian" and Andrew Dickson White. A bear is commonly used as the unofficial mascot, which dates back to the introduction of the mascot "Touchdown" in 1915, a live bear who was brought onto the field during football games.[11] The university's alma mater is "Far Above Cayuga's Waters," and its fight song is "Give My Regards to Davy." People associated with the university are called "Cornellians."

Health

[edit]Cornell offers a variety of professional and peer counseling services to students.[257] Formerly called Gannett Health Services until its name change in 2016, Cornell Health offers on-campus outpatient health services with emergency services and residential treatment provided by Cayuga Medical Center.[258] For most of its history, Cornell provided residential medical care for sick students, including at the historic Sage Infirmary.[259] Cornell offers specialized reproductive health and family planning services.[260] The university also has a student-run Emergency Medical Service (EMS) agency. The squad provides emergency response to medical emergencies on the campus at Cornell and surrounding university-owned properties. Cornell EMS also provides stand-by service for university events and provides CPR, First Aid and other training seminars to the Cornell community.[261]

The university received attention for a series of six student suicides by jumping into a gorge that occurred during the 2009–10 school year, and after the incidents added temporary fences to the bridges which span area gorges.[262] In May 2013, Cornell indicated that it planned to set up nets, which will extend out 15 feet, on five of the university's bridges.[263] Installation of the nets began in May 2013 and were completed over the summer of that year.[262] There were cases of gorge-jumping in the 1970s and 1990s.[264] Before this abnormal cluster of suicides, the suicide rate at Cornell had been similar to or below the suicide rates of other American universities, including a period between 2005 and 2008 in which no suicides occurred.[265][266]

Campus police

[edit]Cornell University Police protect the campus and are classified as peace officers and have the same authority as the Ithaca city police. They are similar to the campus police at Ithaca College, Syracuse University, and University of Rochester because those campus police are classified as armed peace officers. The Cornell University Police are on campus and on-call 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Their duties include: patrolling the university around the clock, responding to emergencies and non-emergency calls for service, crime prevention services, active investigation of crimes on campus, enforcement of state criminal and motor vehicle laws, and campus regulations.[267]

Notable people

[edit]Cornell University has numerous notable faculty and alumni who have gone on to do noteworthy things. As of October 2024, Cornell faculty members, researchers, and alumni include 62 Nobel laureates.[17]

Faculty

[edit]

As of 2023[update], Cornell University had 1,637 full-and part-time professional faculty members affiliated with its main campus, excluding faculty affiliated with Weill Cornell Medical Center, the university's medical school.[16] Since its 1865 founding, many Cornell University's faculty have received global and national recognition across nearly all academic disciplines.

As of the 2005–06 academic year, Cornell faculty included three Nobel laureates, a Crafoord Prize winner, two Turing Award winners, a Fields Medal winner, two Legion of Honor recipients, a World Food Prize winner, an Andrei Sakharov Prize winner, three National Medal of Science winners, two Wolf Prize winners, five MacArthur award winners, four Pulitzer Prize winners, a Carter G. Woodson Scholars Medallion recipient, 20 National Science Foundation career grant holders, a recipient of the National Academy of Sciences Award, a recipient of the American Mathematical Society's Steele Prize for Lifetime Achievement, a recipient of the Heineman Prize for Mathematical Physics, and three Packard Foundation grant holders.[16]

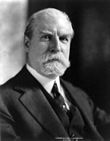

Notable Cornell faculty have included Kurt Lewin, known as the "father of social psychology", who was a Cornell professor from 1933 to 1935.[268] Norman Borlaug, considered the "father of the Green Revolution", taught at the university from 1982 to 1988,[269] and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Congressional Gold Medal, and 49 honorary doctorates.[270] Frances Perkins joined the Cornell faculty in 1952, where she served until her death in 1965, after serving as the first female member of the Cabinet of the United States, where she served as the U.S. Secretary of Labor; Perkins was a witness to the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in her adolescence and, as Secretary of Labor, went on to champion the National Labor Relations Act, the Fair Labor Standards Act, and the Social Security Act. Buckminster Fuller was a visiting professor at Cornell in 1952,[271] and Henry Louis Gates, African American Studies scholar and subject of an arrest controversy and White House "Beer Summit," taught at Cornell from 1985 to 1989.[272] Plant genetics pioneer Ray Wu invented the first method for sequencing DNA, considered a major breakthrough in genetics, since it enabled researchers to more closely understand how genes work.[273][274] Emmy Award-winning actor John Cleese, known for his roles in Monty Python, James Bond, Harry Potter, and Shrek, has taught at Cornell since 1999.[275] Charles Evans Hughes taught in the law school from 1893 to 1895 before becoming Governor of New York, United States Secretary of State, and Chief Justice of the United States.[276] Georgios Papanikolaou, who taught at Cornell's medical school from 1913 to 1961, invented the Pap smear test for cervical cancer.[277] Robert C. Baker ('43), widely credited for inventing the chicken nugget, taught at Cornell from 1957 to 1989. Carl Sagan, who narrated and co-wrote the Emmy and Peabody Award-winning PBS series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage and won a Pulitzer Prize for his book, The Dragons of Eden, was a professor at the university from 1968 to 1996.[278] M. H. Abrams, founding editor of The Norton Anthology of English Literature, was a professor emeritus of English at Cornell.[279] James L. Hoard, a scientist who worked on the Manhattan Project and an expert in crystallography, was a professor emeritus of chemistry and taught from 1936 to 1971.[280] Vladimir Nabokov taught Russian and European literature at Cornell between 1948 and 1959.[281]

(A&S, 1934–2005),

theoretical physicist, Manhattan Project scientist, and 1967 Nobel Prize in Physics recipient

(A&S, 1945–52),

theoretical physicist, Manhattan Project scientist, and 1965 Nobel Prize in Physics recipient

(Law, 1893–95),

44th U.S. Secretary of State, and 11th Supreme Court Chief Justice

(A&S, 1968–96),

co-writer and narrator, Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, and 1978 Pulitzer Prize recipient

Alumni

[edit]

As of 2024, Cornell University had over 250,000 living alumni,[282] including 34 Marshall Scholars and 31 Rhodes Scholars.[16][18] Cornell is the only university or college in the world with four female alumni, Pearl S. Buck, Barbara McClintock, Toni Morrison, and Claudia Goldin, who have won unshared Nobel Prizes.[17][283] Many alumni maintain university ties through the annual homecoming reunion weekend each fall, through Cornell Magazine distributed to alumni,[284] and through the Cornell Club of New York in Manhattan. In 2015, Cornell ranked fifth nationally among U.S. universities and colleges for gifts and bequests from alumni.[285]

Cornell University alumni are noted for their accomplishments in public, professional, and corporate life.[16][286] Cornell alumni include four heads of state, Lee Teng-hui, President of Taiwan from 1988 to 2000,[287] Tsai Ing-wen, the first female president of Taiwan from 2016 to 2024,[288] Mario García Menocal, the President of Cuba from 1913 to 1921,[289] and Jamshid Amuzegar ('50), Prime Minister of Iran from 1977 to 1978.[290]

Among senior U.S. government officials, Cornell alumni include Janet Reno ('60), the first female U.S. Attorney General,[291] and Ruth Bader Ginsburg ('54), a former U.S. Supreme Court associate justice.[292] Among foreign governments, Hu Shih (1914) was a Chinese reformer and ambassador of China to the U.S. and United Nations.[293]

In academia, alumnus David Starr Jordan (1872) was founding president of Stanford University,[294] and M. Carey Thomas (1877) was the second president and first female president of Bryn Mawr College.[295]

In military service, Matt Urban ('41), a Medal of Honor recipient, holds the distinction as one of the most decorated soldiers in World War II.[296]

In business, Cornellians include Citigroup CEO Sanford Weill ('55),[297](p42) Goldman Sachs Group chairman Stephen Friedman ('59),[298] Kraft Foods CEO Irene Rosenfeld ('75, '77, '80),[299] Autodesk CEO Carl Bass ('83),[300] Aetna CEO Mark Bertolini ('84),[301] S.C. Johnson & Son CEO Fisk Johnson ('79, '80, '82, '84, '86),[302] Chevron Chairman Kenneth T. Derr ('59),[303] Sprint Nextel CEO Dan Hesse ('77),[304] Verizon CEO Lowell McAdam ('76),[305] MasterCard CEO Robert Selander ('72),[306] Coors Brewing Company CEO Adolph Coors III ('37),[307] Loews Corporation Chairman Andrew Tisch ('71),[308] Burger King founder James McLamore ('47),[309] Hotels.com founder David Litman ('79),[310] PeopleSoft founder David Duffield ('62),[311] Priceline.com founder Jay Walker ('77),[312] Staples founder Myra Hart ('62),[313] Qualcomm founder Irwin M. Jacobs ('56),[314] Tata Group CEO Ratan Tata ('62),[315]Nintendo of America President and COO Reggie Fils-Aimé,[316] Johnson & Johnson worldwide chairman Sandi Peterson,[317] Pawan Kumar Goenka, MD of Mahindra & Mahindra, and Y Combinator founder Paul Graham ('86).

In medicine, alumnus Robert Atkins ('55) developed the Atkins Diet,[318] Henry Heimlich ('47) developed the Heimlich maneuver,[319] Wilson Greatbatch ('50) invented the pacemaker,[320] James Maas ('66; also a faculty member) coined the term power nap,[321] C. Everett Koop ('41) served as Surgeon General of the United States,[322] and Anthony Fauci served as Chief Medical Advisor to the President during the COVID-19 pandemic.[323][324][325]

Among inventors, Cornellians include Thomas Midgley Jr. ('11), who invented Freon,[326] Jon Rubinstein ('78), who is credited with the development of the iPod,[327] and Robert Tappan Morris, who developed the first computer worm on the Internet.

In science, Bill Nye ('77) is known as "The Science Guy."[328] Clarence W. Spicer invented the 'universal joint' for automobiles while a student in 1903.

Eight Cornellians have served as NASA astronauts. Steve Squyres ('81) is the principal investigator on the Mars Exploration Rover Mission.[329] In aerospace, Otto Glasser ('40) directed the U.S. Air Force program that developed the SM-65 Atlas, the world's first operational Intercontinental ballistic missile. Yolanda Shea is a research scientist in the Science Directorate at the Langley Research Center.[330]

In literature, Toni Morrison (M.A.'50; Nobel laureate) authored the novel Beloved, Pearl S. Buck (M.A.'25; Nobel laureate) authored The Good Earth,[331] and Thomas Pynchon ('59) wrote canonical works of post-World War II fiction, including Gravity's Rainbow and The Crying of Lot 49. Junot Díaz ('95) wrote The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao for which he won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction,[332] and E. B. White (1921) authored Charlotte's Web and Stuart Little.[333] Kurt Vonnegut, who attended but did not graduate, wrote extensively for The Cornell Daily Sun during his studies at Cornell and went on to author Slaughterhouse-Five and Cat's Cradle. Lauren Weisberger ('99) wrote The Devil Wears Prada, which was later adapted into a 2006 film of the same name starring Meryl Streep and Anne Hathaway.

In media, Cornell alumni include liberal commentators Bill Maher ('78) and Keith Olbermann ('79)[334] and conservative author Ann Coulter ('84).[297](p41)

In theatre and entertainment, Cornell alumni include actor Christopher Reeve ('74), who played Superman,[297](p42) Frank Morgan, who played the title role of The Wizard in the MGM movie The Wizard of Oz, and Peter Yarrow ('59) of the folk band Peter, Paul and Mary, who wrote the song Puff, the Magic Dragon, and other classic songs. Howard Hawks ('18) directed classic films, including Bringing Up Baby (1938), His Girl Friday (1940), and Rio Bravo (1959).

In architecture, alumnus Richmond Shreve (1902) designed the Empire State Building,[335] and Raymond M. Kennedy ('15) designed Hollywood's famous Grauman's Chinese Theatre.[336] In the arts, Arthur Garfield Dove (1903) is often considered the first American abstract painter. Louise Lawler ('69) is a pioneering feminist artist, photographer, and member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

In athletics, Cornell graduates include football legend Pop Warner (1894),[337] head coach of the U.S. men's national soccer team Bruce Arena ('73),[338] Major League Baseball commissioner Rob Manfred ('80)[339] National Hockey League commissioner Gary Bettman ('74),[340] six-time Stanley Cup winning hockey goalie Ken Dryden ('69),[341] tennis singles world # 2 Dick Savitt,[342] seven-time US Tennis championships winner William Larned, Toronto Raptors president Bryan Colangelo ('87),[343] and Kyle Dake, four-time NCAA division I college wrestling national champion.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The others are the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Tuskegee University.

- ^ The university's charter was amended on 24 April 1867, to specify alumni-elected trustees;[25] however, that provision was not implemented until there were at least 100 alumni[26] in 1872.[27] Also in 1865, the election of the Harvard University Board of Overseers was shifted to alumni voting.

- ^ Other consists of Multiracial Americans & those who prefer to not say.

- ^ The percentage of students who received an income-based federal Pell grant intended for low-income students.

- ^ The percentage of students who are a part of the American middle class at the bare minimum.

References

[edit]- ^ The Celebration of the Two Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary of the Royal Society of London, July 15-19, 1912. Royal Society. 1913. p. 74.

- ^ Altschuler, Glenn C.; Kramnick, Isaac (2014). Cornell: a history, 1940-2015. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 355. ISBN 9780801471889.

- ^ Berg, Alex (21 August 2007). "C.U. Motto Earns Top Rank". The Cornell Daily Sun. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ "Cornell University Mission". Cornell University. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ^ a b "University endowment posts 'strong' gain in FY 2024" (Press release). Cornell University News Service. 15 October 2024. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- ^ "Consolidated Financial Statements: June 30, 2023 and 2022" (PDF). cornell.edu (Press release). Cornell University.

- ^ a b c d e "Student Enrollment". University Factbook. Cornell University. 1 November 2023. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ "Cornell University". IPEDS. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ "Cornell University". Middle States Commission on Higher Education.

- ^ "Colors". Cornell University Brand Center. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ a b Holmes, Casey (30 April 2006). "Wild Cornell Mascot Wreaks Havoc". The Cornell Daily Sun. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- ^ a b "Colleges and Schools". cornell.edu. Cornell University. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ "Statistics". marshallscholarship.org. Marshall Scholarship. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ "Wealth-X Applied Wealth Intelligence" (PDF).

- ^ Hess, Abigail (29 November 2018). "University of Wisconsin produced the most current Fortune 500 CEOs — here's how 29 other schools stack up". CNBC. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Factbook" (PDF). Cornell University. October 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2006. Retrieved 27 December 2009.

- ^ a b c "Nobel laureates affiliated with Cornell University". Cornell Chronicle (Press release). Cornell News Service. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Uncle Ezra". Cornell University. Archived from the original on 2 January 2007. Retrieved 10 January 2007.

- ^ "Chapter 585: An act to establish the Cornell University ...". Laws of New York. Laws of the State of New York Passed at the Sessions of the Legislature (Report). Vol. 88th sess. 1865. pp. 1188–1194. hdl:2027/nyp.33433090742218. ISSN 0892-287X. enacted 27 April 1865.

- ^ Becker, Carl L. (1943). Cornell University: Founders and the founding. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9058-3. Retrieved 17 June 2006.

- ^ "How old is Cornell?". cornell.edu. Facts about Cornell. Cornell University. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ "The Early History of District Energy at Cornell University". Cornell University. Archived from the original on 4 July 2007. Retrieved 24 November 2009.

- ^ Gelber, Sidney (2001). Politics and Public Higher Education in New York State: Stony Brook: A case history. New York, NY: P. Lang. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-8204-4919-7.