Sandy Spring, Maryland

Sandy Spring | |

|---|---|

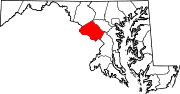

Location in the U.S. state of Maryland | |

| Coordinates: 39°08′58.3″N 77°01′34.42″W / 39.149528°N 77.0262278°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| Settled | ca. 1715[1] |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 20860 |

| Area codes | 301, 240 |

Sandy Spring is an unincorporated community in Montgomery County, Maryland, United States.[2]

Geography

[edit]Sandy Spring's boundaries are roughly defined as Brooke Road and Dr. Bird Road to the north and west, Ednor Road to the south, and New Hampshire Avenue to the east.[3]

The United States Census Bureau combines Sandy Spring with the nearby community of Ashton to form the census-designated place of Ashton-Sandy Spring,[3] and all census data are tabulated for this combined entity.

History

[edit]

The community was founded by Quakers who arrived in the early 18th century[3] searching for land where they could grow tobacco and corn.

One of the very early land owners in the Sandy Spring area was Richard Snowden, who patented (purchased) the 1,000 acres (4 km2) "Snowden's Manor" in 1715.[1] Snowden gradually enlarged his property with additional land purchases over the next few decades until it was surveyed at over 9,000 acres (36 km2) as "Snowden's Manor Enlarged" in 1743.

Another important early landowner, Major John Bradford, had patented over 2,000 acres (8 km2) in the Sandy Spring area, including "Charley Forest" in 1716,[1] "Charley Forest Enlarged", "Higham", and "Discovery." Bradford sold off large parts of these properties, but Snowden's son-in-law, James Brooke, later bought up the original Charley Forest land as well as other land in the area, eventually owning over 22,000 acres (90 km2) by the 1760s.[4]

The Quakers built their current brick meeting house in 1817, replacing a 1770 frame meeting house. Quakers first began worshiping in the area circa 1753.[1][5][6] The site is near a fresh-water spring that gave its name to the community.[3] The location of this meeting house in the village of Sandy Spring helped to define the geographic extent of the greater Sandy Spring neighborhood of the time, comprising those areas from which members of the Meeting could travel to and from the meeting house by horse or carriage in one day, arriving home before sunset. The greater Sandy Spring neighborhood thus includes the current communities of Brookeville, Olney, Norbeck, Ednor, Brighton, and other communities within a six-mile radius of the meeting house.[7]

In the late 19th century the community started a local school called the Sherwood Academy. This school was turned over to the Government of Montgomery County in 1906 to become Sherwood High School, the county's third public high school. A Quaker school, Sandy Spring Friends School, was established in 1961. In 1967 a Quaker retirement community, Friends House, was founded next to the school. The Sandy Spring Library opened behind the Sandy Spring Store in 1842.[1] The Farmer's Club of Sandy Spring was established in 1844 to discuss preferable methods of farming.[1]

A 1901 Department of Labor study documented hundreds of residents who trace their lineage 125 years to free black families.[8]

Benjamin Hallowell

[edit]Benjamin Hallowell (educator) (1799–1887) was a prominent Quaker in 19th century Sandy Spring. As an educator, he taught at Fair Hill in Olney, then taught in Virginia. He lived at Rockland in Olney. His farm is now the Hallowell housing development. He briefly served as the first president of the Maryland Agricultural College (later to become the University of Maryland.) He was integral in forming the Sandy Spring Farmer's Club and the Mutual Fire Insurance Company.[9]

Dr. Bird

[edit]Dr Jacob Wheeler Bird was born in Anne Arundel County in 1885.[10] He attended St. John's College in Annapolis, and he earned his medical degree from the University of Maryland, Baltimore in 1907.[10]

In 1909, Dr. Bird moved to Sandy Spring to set up his medical practice on the road now named for him, Dr. Bird Road.[10] He also established the first hospital located in Montgomery County, now called Montgomery General Hospital.[10]

During his fifty-year medical career, Dr. Bird made house calls to his patients, at first in a horse-drawn buggy and later an automobile.[10] He founded Montgomery General Hospital in February 1920.

Dr. Bird and his wife died in an automobile accident in Alabama on October 25, 1959.[10]

Sandy Spring Museum

[edit]

An insurance salesman and auctioneer named Delmas Wood started the Sandy Spring Museum in 1980 because he thought Sandy Spring's history was gradually being lost as older residents died.[11] Wood wanted a place to preserve antique furniture, farm equipment, photographs, paintings, and documents of the Sandy Spring area.[12] Florence Virginia Barrett Lehman also helped found the museum.[13]

The museum was originally located in the basement of a Sandy Spring National Bank branch in Olney.[14] In October 1986,[15] it moved to Tall Timbers, a brick four-story Colonial house that had been the home of Gladys Brooke Tumbleson, who had died earlier that year.[11] Tumbleson descended from the Brooke family, for which nearby Brookeville was named.[11] Tumbleson sold the building to the museum for less than market value.[11]

Helen Bentley donated 7.5 acres (30,000 m2) of land on Bentley Road in Sandy Spring to the museum in 1994.[12] The museum's new building on opened in 1997, providing more room for the museum's exhibits.[14]

In 2007, an addition opened, providing a research library and a collections storage facility for the museum.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Thruston, Lucy Meacham (December 24, 1905). "Notable Neighborhood: The History And Traditions Of Sandy Spring". The Baltimore Sun. p. 8. ProQuest 537095830.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Sandy Spring, Maryland

- ^ a b c d Glaros, Tony (October 4, 2014). "Where We Live: Sandy Spring, Md., is where FDR and Herbert Hoover played". The Washington Post. p. RE3.

- ^ Eldon, Hiebert Ray; MacMaster, Richard K. (1976). A Grateful Remembrance: The Story of Montgomery County, Maryland. Rockville, Maryland: Montgomery County Government and the Montgomery County Historical Society.

- ^ Moore, Brook. "Sandy Spring Friends Meeting House National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form". National Archives Catalog. United States Department of the Interior National Park Service. p. 2. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ^ Trieschmann, Laura. "Sandy Spring Historic District Determination of Eligibility Form" (PDF). Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties. Maryland Historical Trust. p. 2. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ^ Canby, Thomas Y. and Elie S. Rogers (1979). Sandy Spring Legacy. Sandy Spring: Sandy Spring Museum.

- ^ "THE Negroes of Sandy Spring". The Baltimore Sun. February 15, 1901. p. 4. ProQuest 536271700.

- ^ Canby, Thomas Y. and Elie S. Rogers (1979). Sandy Spring Legacy. Sandy Spring: Sandy Spring Museum.

- ^ a b c d e f Andersen, Patricia Abelard (Winter 2011), "Automobiles in Early Twentieth Century Montgomery County", The Montgomery County Story, vol. 54, no. 2, p. 18

- ^ a b c d Meyer, Eugene L. (October 10, 1985). "Museum and Residents Bear Witness To Quaker Tradition of Sandy Spring". The Washington Post. p. MD1.

- ^ a b Bernstein, Adam (August 24, 2000). "A Window Into Town's Past". The Washington Post. p. M21.

- ^ "Florence Lehman, a former Herald reporter, at 84" (obituary). Boston Herald. March 4, 1996.

- ^ a b Ruben, Barbara (September 8, 2001). "Town's Quaker Roots A Calming Influence". The Washington Post. p. J1.

- ^ Kessler, Pamela (June 6, 1986). "Maryland Museum Guide". The Washington Post. p. M14.

- ^ "Our Story". Sandy Spring Museum. Retrieved October 28, 2015.

External links

[edit] Media related to Sandy Spring, Maryland at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sandy Spring, Maryland at Wikimedia Commons- Brooke Family papers at the University of Maryland Libraries. The Brooke family was a large Quaker family living in Sandy Spring, Maryland. The collection contains the diaries of several women in the family