Milledgeville, Georgia

Milledgeville, Georgia | |

|---|---|

| City of Milledgeville | |

| |

| Motto(s): "Capitols, Columns and Culture" | |

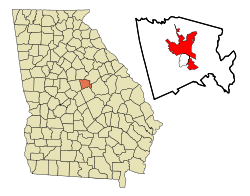

Location in Baldwin County and the state of Georgia | |

| Coordinates: 33°5′16″N 83°14′0″W / 33.08778°N 83.23333°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Baldwin |

| Incorporated | December 12, 1804 |

| Named for | John Milledge |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–Manager |

| • Mayor | Mary Parham-Copelan |

| • Manager | Barry Jarrett |

| • Council | Members

|

| Area | |

• Total | 20.48 sq mi (53.05 km2) |

| • Land | 20.32 sq mi (52.63 km2) |

| • Water | 0.16 sq mi (0.42 km2) |

| Elevation | 330 ft (100 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 17,070 |

| • Density | 839.98/sq mi (324.31/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Code | 31061 |

| Area code | 478 |

| FIPS code | 13-51492[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0332390[4] |

| Website | milledgevillega |

Milledgeville is a city in and the county seat of Baldwin County in the U.S. state of Georgia.[5] It is northeast of Macon, bordered on the east by the Oconee River. The rapid current of the river here made this an attractive location to build a city. It was the capital of Georgia from 1804 to 1868, including during the American Civil War. Milledgeville was preceded as the capital city by Louisville and was succeeded by Atlanta, the current capital. Today U.S. Highway 441 connects Milledgeville to Madison, Athens, and Dublin.

As of April 1, 2020, the population of Milledgeville was 17,070, down from 17,715 at the 2010 U.S. census.[6]

Milledgeville is along the route of the Fall Line Freeway, which is under construction to link Milledgeville with Augusta, Macon, Columbus, and other Fall Line cities. They have long histories from the colonial era of Georgia.

Milledgeville is the principal city of the Milledgeville micropolitan statistical area, a micropolitan area that includes Baldwin and formerly Hancock county until 2023.[7] It had a population of 43,799 at the 2020 census.[3] The Old State Capitol is located here; it was added to the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). Much of the original city is contained within the boundaries of the Milledgeville Historic District, which was also added to the NRHP.

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2018) |

Milledgeville, named after Georgia governor John Milledge (1802–1806), was founded by European Americans at the start of the 19th century as the new centrally located capital of the state of Georgia. It served as the state capital from 1804 to 1868.

In 1803 an act of the Georgia legislature called for the establishment and survey of a town to be named in honor of the current governor, John Milledge. The Treaty of Fort Wilkinson (1802) had recently forced Native American tribes to cede territory immediately west of the Oconee River. The white population of Georgia continued to press west and south in search of new farmland. The town of Milledgeville was developed in an area that had long been occupied by indigenous peoples.

In December 1804 the state legislature declared Milledgeville the new capital of Georgia. The new planned town, modeled after Savannah and Washington, D.C., stood on the edge of the frontier at the Atlantic fall line, where the Upper Coastal Plain meets the foothills and plateau of the Piedmont. The area was surveyed, and a town plat of 500 acres (2.0 km2) was divided into 84 4-acre (16,000 m2) squares. The survey also included four public squares of 20 acres (81,000 m2) each.

Life in the antebellum capital

[edit]

After 1815 Milledgeville became increasingly prosperous and more respectable. Wealth and power gravitated toward the capital. Much of the surrounding countryside was developed by slave labor for cotton plantations, which was the major commodity crop of the South. Cotton bales regularly were set up to line the roads, waiting to be shipped downriver to Darien.

Public-spirited citizens such as Mayor Tomlinson Fort (1847–1848) promoted better newspapers, learning academies, and banks. In 1842 Central State Hospital) was built here. Oglethorpe University, where the poet Sidney Lanier was later educated, opened its doors in 1838. (The college, forced to close in 1862 during the war, was rechartered in 1913. It moved its campus to Atlanta.)

The cotton boom in this upland area significantly increased the demand for slave labor. The town market, where slave auctions took place, was located on Capital Square, next to the Presbyterian church. Skilled black carpenters, masons, and laborers were forced to construct most of the handsome antebellum structures in Milledgeville.[8]

Two events epitomized Milledgeville's status as the political and social center of Georgia in this period:

- In 1825 the capital was visited by American Revolutionary War hero and aristocrat, the Marquis de Lafayette. The receptions, barbecue, formal dinner, and grand ball for the veteran apostle of liberty seemed to mark Milledgeville's coming of age.

- The Governor's Mansion was constructed (1836-38/39); it was one of the most important examples of Greek revival architecture in America.

By 1854 Baldwin County had a total population of 8,148, of whom 3,566 were free (mostly white), and 4,602 were African American slaves.

American Civil War and its aftermath

[edit]

On January 19, 1861, Georgia convention delegates passed the Ordinance of Secession, and on February 4, 1861, the "Republic of Georgia" joined the Confederate States of America. In November 1864, Union General William T. Sherman and 30,000 Union troops marched into Milledgeville during his March to the Sea. Governor Joseph E. Brown had already packed up the rugs and curtains from the Governor's Mansion, and fled town with other political and military leaders, leaving the public unprotected.[10] Sherman largely spared the town destruction, though burned some buildings with military uses.[11] Sherman's troops are claimed to have poured sorghum and molasses down the pipes of the organ at St. Stephen's Episcopal Church;[12] the organ was replaced by New York Life Insurance Company.[13]

In 1868, during Reconstruction, the state legislature moved the capital to Atlanta—a city emerging as the symbol of the New South as surely as Milledgeville symbolized the Old South.

Milledgeville struggled to survive as a city after losing the business of the capital. The energetic efforts of local leaders established the Middle Georgia Military and Agricultural College (later Georgia Military College) in 1879 on Statehouse Square. Where the crumbling remains of the old penitentiary stood, Georgia Normal and Industrial College (later Georgia College & State University) was founded in 1889. In part because of these institutions, as well as Central State Hospital, Milledgeville developed as a less provincial town than many of its neighbors.

Twentieth century to present

[edit]In the 1950s the Georgia Power Company completed a dam at Furman Shoals on the Oconee River, about 5 miles (8 km) north of town, creating a huge reservoir called Lake Sinclair. The lake community became an increasingly important part of the town's social and economic identity.

In the 1980s and 1990s Milledgeville began to capitalize on its heritage by revitalizing the downtown and historic district. It encouraged restoration of historic buildings and an urban design scheme on Main Street to emphasize its character.

By 2000 the population of Milledgeville and Baldwin County combined had grown to 44,700. Community leaders have made concerted efforts to create a more diversified economic base, striving to wean the old capital from its dependence on government institutions such as Central State Hospital and state prisons. The state has recently[when?] closed some prisons and reduced jobs at Central State, due to tightening state budgets.

Geography

[edit]Milledgeville is located at 33°5′16″N 83°14′0″W / 33.08778°N 83.23333°W (33.087755, -83.233401)[14] and is 330 feet (100 m) above sea level.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 20.6 square miles (53.3 km2), of which 20.4 square miles (52.9 km2) is land and 0.15 square miles (0.4 km2), or 0.74%, is water.[15]

U.S. Route 441 is the main route through the city, leading north 21 mi (34 km) to Eatonton and south 22 mi (35 km) to Irwinton. Georgia State Routes 22, 24, and 49 also run through the city as well. GA-22 leads northeast 24 mi (39 km) to Sparta and southwest 20 mi (32 km) to Gray. GA-24 leads east 29 mi (47 km) to Sandersville and north to Eatonton with U.S. 441. GA-49 leads southwest 30 mi (48 km) to Macon.

Milledgeville is located on the Atlantic Seaboard fall line of the United States. The Oconee River flows a half mile east of downtown on its way south to the Altamaha River and then south to the Atlantic Ocean. Lake Sinclair, a man-made lake, is about 5 miles (8 km) northeast of Milledgeville on the border of Baldwin, Putnam and Hancock counties.

Milledgeville is composed of two main districts: a heavily commercialized area along the highway known to locals simply as "441," extending from a few blocks north of Georgia College & State University to 4 miles (6 km) north of Milledgeville, and the "Downtown" area, encompassing the college, buildings housing city government agencies, various bars and restaurants. This historic area was laid out in 1803, with streets named after other counties in Georgia.

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Milledgeville, Georgia, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1891–2017 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 83 (28) |

86 (30) |

94 (34) |

98 (37) |

101 (38) |

109 (43) |

110 (43) |

110 (43) |

108 (42) |

99 (37) |

90 (32) |

83 (28) |

110 (43) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 74.1 (23.4) |

77.9 (25.5) |

84.3 (29.1) |

88.6 (31.4) |

93.3 (34.1) |

98.9 (37.2) |

100.1 (37.8) |

100.0 (37.8) |

95.2 (35.1) |

88.6 (31.4) |

82.2 (27.9) |

75.5 (24.2) |

102.1 (38.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 58.0 (14.4) |

61.9 (16.6) |

69.4 (20.8) |

76.7 (24.8) |

84.1 (28.9) |

89.7 (32.1) |

93.2 (34.0) |

91.4 (33.0) |

86.3 (30.2) |

77.5 (25.3) |

67.8 (19.9) |

60.3 (15.7) |

76.4 (24.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 45.5 (7.5) |

49.0 (9.4) |

55.6 (13.1) |

62.7 (17.1) |

71.0 (21.7) |

78.2 (25.7) |

81.8 (27.7) |

80.6 (27.0) |

75.1 (23.9) |

64.7 (18.2) |

54.2 (12.3) |

48.1 (8.9) |

63.9 (17.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 33.0 (0.6) |

36.1 (2.3) |

41.9 (5.5) |

48.8 (9.3) |

57.9 (14.4) |

66.8 (19.3) |

70.3 (21.3) |

69.8 (21.0) |

63.9 (17.7) |

52.0 (11.1) |

40.5 (4.7) |

35.9 (2.2) |

51.4 (10.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 16.6 (−8.6) |

20.2 (−6.6) |

25.7 (−3.5) |

32.8 (0.4) |

43.6 (6.4) |

56.0 (13.3) |

62.4 (16.9) |

61.0 (16.1) |

48.9 (9.4) |

34.8 (1.6) |

26.3 (−3.2) |

19.0 (−7.2) |

13.3 (−10.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −3 (−19) |

8 (−13) |

13 (−11) |

25 (−4) |

37 (3) |

45 (7) |

54 (12) |

53 (12) |

36 (2) |

24 (−4) |

10 (−12) |

1 (−17) |

−3 (−19) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.23 (107) |

4.06 (103) |

4.75 (121) |

3.90 (99) |

3.16 (80) |

4.30 (109) |

4.16 (106) |

4.73 (120) |

4.22 (107) |

2.83 (72) |

3.36 (85) |

4.49 (114) |

48.19 (1,223) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.3 (0.76) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.6 (1.52) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.4 | 8.9 | 9.2 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 10.6 | 11.0 | 11.1 | 7.9 | 6.9 | 7.7 | 9.5 | 108.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| Source 1: NOAA[16] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service (mean maxima/minima 1981–2010)[17] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1810 | 1,256 | — | |

| 1820 | 2,069 | 64.7% | |

| 1840 | 2,095 | — | |

| 1850 | 2,216 | 5.8% | |

| 1860 | 2,480 | 11.9% | |

| 1870 | 2,750 | 10.9% | |

| 1880 | 3,800 | 38.2% | |

| 1890 | 3,322 | −12.6% | |

| 1900 | 4,219 | 27.0% | |

| 1910 | 4,385 | 3.9% | |

| 1920 | 4,619 | 5.3% | |

| 1930 | 5,534 | 19.8% | |

| 1940 | 6,778 | 22.5% | |

| 1950 | 8,835 | 30.3% | |

| 1960 | 11,117 | 25.8% | |

| 1970 | 11,601 | 4.4% | |

| 1980 | 12,176 | 5.0% | |

| 1990 | 17,727 | 45.6% | |

| 2000 | 18,757 | 5.8% | |

| 2010 | 17,715 | −5.6% | |

| 2020 | 17,070 | −3.6% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[18] | |||

| Race | Num. | Perc. |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 8,055 | 47.19% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 7,685 | 45.02% |

| Native American | 23 | 0.13% |

| Asian | 280 | 1.64% |

| Pacific Islander | 16 | 0.09% |

| Other/Mixed | 456 | 2.67% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 555 | 3.25% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 17,070 people, 5,895 households, and 2,852 families residing in the city.

Government

[edit]The Milledgeville City Council is the city's legislative body, with the power to enact all ordinances and resolutions and controls the funding of all designated programs. Six council members are elected to represent their district, while the mayor is elected at-large, by city voters, for a four-year term.

City Council meetings are held on the second and fourth Tuesday of the month. Meetings are open to the public and televised locally on MBC TV-4 Milledgeville/Baldwin County Governmental/Educational Access Cable Channel on local Charter Communications.

In the November 2017 general election, incumbent Mayor Gary Thrower was defeated by Mary Parham-Copelan. She was sworn in as the city's first African American female mayor on December 29, 2017.[20]

Elected officials as of October 2023[update]:[21]

- Mayor: Mary Parham-Copelan[22]

- Council District 1: Dr. Collinda Lee

- Council District 2: Jeanette Walden

- Council District 3: Denese Shinholster

- Council District 4: Walter Reynolds

- Council District 5: Shonya Mapp

- Council District 6: Stephen Chambers – Council President Pro-Tem

Education

[edit]Milledgeville's public school system is governed by the Baldwin County School District.

Public elementary schools

[edit]- Lakeview Academy

- Lakeview Primary

- Midway Hills Academy

- Midway Hills Primary

Public middle school

[edit]Public high school

[edit]Private schools

[edit]- Georgia Military College prep school (grades K–12)

- John Milledge Academy (grades K–12)

Schools for higher education

[edit]

- Central Georgia Technical College

- Georgia College & State University (commonly known as Georgia College)

- Georgia Military College

Libraries

[edit]Milledgeville's public library system is part of the Middle Georgia Regional Library System. Mary Vinson Memorial Library is located downtown. Georgia College & State University also has a library.

Historic schools

[edit]The school system building facilities were revamped during the 1990s and first decade of the 21st century, with all new buildings, including a new Board of Education office. This required relocation and merging of older schools. The concept of a middle school was introduced, whereas previously 6th through 9th grades were housed in separate schools. Closed older schools include:

- Northside Elementary School (now a shopping center)

- Southside Elementary School (now a church)

- West End Elementary School (torn down)

- Harrisburg Elementary School (torn down)

- Baldwin Middle School (was located in old Baldwin High School) no

- Boddie Junior High School (8th and 9th grades)

- Baldwin High School (old location)

- Carver Elementary School (5th and 6th grades / now an alternate school)

- Sallie Davis Middle School (7th grade)

Transportation

[edit]Major roads

[edit] U.S. Route 441

U.S. Route 441

- U.S. Route 441 Business

State Route 22

State Route 22 State Route 49

State Route 49

Pedestrians and cycling

[edit]Notable people

[edit]- Melvin Adams, Jr, better known as Fish Scales from the band Nappy Roots

- Andrew J. Allen, concert saxophonist

- Nathan Crawford Barnett, Georgia Secretary of State for more than 30 years

- Ella Barksdale Brown, journalist, educator

- Kevin Brown, professional baseball player

- Javon Bullard, college football player for the University of Georgia

- Tasha Butts, basketball player and coach

- Wally Butts, college football coach

- Earnest Byner, professional football player

- Lisa D. Cook, American economist[23]

- Pete Dexter, novelist, journalist and screenwriter

- George Doles, Confederate Brigadier General

- Henry Derek Elis, vocalist for heavy metal supergroup Act of Defiance

- Tillie K. Fowler, politician

- Joel Godard, television announcer

- Marjorie Taylor Greene, United States Representative

- Willie Greene, professional baseball player

- Floyd Griffin, mayor of Milledgeville, state representative, state senator[24]

- Oliver Hardy, motion picture comedian

- Nick Harper, professional football player

- Charles Holmes Herty, academic, scientist, businessman and first football coach at the University of Georgia

- Leroy Hill, professional football player

- Maurice Hurt, professional football player

- Edwin Francis Jemison, Civil War soldier who died in battle

- Sherrilyn Kenyon, author[25]

- Grace Lumpkin, writer

- William Gibbs McAdoo, US Secretary of the Treasury

- David Brydie Mitchell, the only Governor of Georgia buried in Milledgeville

- Celena Mondie-Milner, professional track and field player

- Powell A. Moore, politician and public servant

- Otis Murphy, international saxophone soloist and professor at Indiana University Jacobs School of Music

- Flannery O'Connor, author, winner of the 1972 U.S. National Book Award for Fiction

- Ulrich Bonnell Phillips, historian

- Barry Reese, writer

- Lucius Sanford, professional football player

- Carrie Bell Sinclair, poet

- Tut Taylor, bluegrass musician

- Ellis Paul Torrance, psychologist

- Larry Turner, professional basketball player

- William Usery Jr., labor union activist and U.S. Secretary of Labor

- Carl Vinson, congressman

- J. T. Wall, professional football player

- Rico Washington, professional baseball player

- Rondell White, professional baseball player

- Robert McAlpin Williamson, Republic of Texas Supreme Court Justice and Texas Ranger

See also

[edit]- Bartram Educational Forest

- List of municipalities in Georgia

- Lockerly Arboretum

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Baldwin County, Georgia

References

[edit]- ^ "Milledgeville City Hall". 2017. Archived from the original on May 4, 2017. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 18, 2021.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "QuickFacts Milledgeville city, Georgia". United States Census Bureau. n.d. Archived from the original on June 26, 2019. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ^ MICROPOLITAN STATISTICAL AREAS AND COMPONENTS, Office of Management and Budget, 2007-05-11. Accessed 2008-07-27.

- ^ Wilson, Robert J. "Milledgeville". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on September 2, 2019. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ "Georgia Penitentiary at Milledgeville".

- ^ "Sherman's March: 150 years later".

- ^ "A trip through Georgia's Civil War memories, past". May 28, 2017.

- ^ "Civil War Milledgeville FAQ". Ina Dillard Russell Library. Georgia College & State University. Retrieved February 17, 2024.

- ^ "St. Stephen's Episcopal Church, Milledgeville Georgia".

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Milledgeville city, Georgia (Revision published Jan. 25, 2013)". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Milledgeville, GA". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ "NOAA Online Weather Data – NWS Atlanta". National Weather Service. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 17, 2021.

- ^ Hobbs, Billy (November 7, 2017). "Parham-Copelan upsets Thrower in mayor's race". The Union-Recorder. Archived from the original on February 9, 2018. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ "Milledgeville City Hall - City Council". www.milledgevillega.us. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- ^ "Milledgeville City Hall - Mayor's Office". www.milledgevillega.us. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- ^ "Women in Economics: Lisa Cook". Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ Hobbs, Billy (March 2021). "Milledgeville's first Black state senator, mayor honored". The Union-Recorder. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ Staples, Gracie Bonds. "This Life: Author's dark tales an escape from darkness in her own life". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Further reading

[edit]- Strong, Robert Hale (1961). Halsey, Ashley (ed.). A Yankee Private's Civil War. Chicago: Henry Regnery Company. pp. 67–70. LCCN 61-10744. OCLC 1058411.

External links

[edit]- Government

- General information

Geographic data related to Milledgeville, Georgia at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Milledgeville, Georgia at OpenStreetMap- Milledgeville, Georgia at City-Data.com

- Milledgeville, Georgia Archived January 16, 2013, at the Wayback Machine at New Georgia Encyclopedia

- Milledgeville – Baldwin County Convention & Visitors Bureau

- Milledgeville Historic Newspapers Archive at Digital Library of Georgia

- Milledgeville, Georgia

- 1804 establishments in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Cities in Baldwin County, Georgia

- Cities in Georgia (U.S. state)

- County seats in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Former state capitals in the United States

- Milledgeville micropolitan area, Georgia

- Planned communities in the United States

- Populated places established in 1804