Bhutan

Kingdom of Bhutan | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: འབྲུག་ཙན་དན Druk Tsenden "The Thunder Dragon Kingdom" | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Thimphu 27°28.0′N 89°38.5′E / 27.4667°N 89.6417°E |

| Official languages | Dzongkha |

| Religion | |

| Demonym(s) | Bhutanese |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary semi-constitutional monarchy |

| Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck | |

| Tshering Tobgay | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| National Council | |

| National Assembly | |

| Formation | |

• Unification of Bhutan | 1616–1634 |

• Period of Desi administration | 1650–1905 |

• Start of the Wangchuck dynasty | 17 December 1907 |

| 8 August 1949 | |

| 21 September 1971 | |

| 18 July 2008 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 38,394 km2 (14,824 sq mi)[3][4] (133rd) |

• Water (%) | 1.1 |

| Population | |

• 2021 estimate | 777,486[5][6] (159th) |

• 2022 census | 727,145[7] |

• Density | 20.3/km2 (52.6/sq mi) (210th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2022) | low inequality |

| HDI (2022) | medium (125th) |

| Currency | Ngultrum (BTN) |

| Time zone | UTC+06 (BTT) |

| Date format | YYYY-MM-DD |

| Drives on | left[11] |

| Calling code | +975 |

| ISO 3166 code | BT |

| Internet TLD | .bt |

| |

Bhutan,[a] officially the Kingdom of Bhutan,[b][14] is a landlocked country in South Asia situated in the Eastern Himalayas between China in the north and India in the south. With a population of over 727,145[15] and a territory of 38,394 square kilometres (14,824 sq mi), Bhutan ranks 133rd in land area and 160th in population. Bhutan is a constitutional monarchy with a king (Druk Gyalpo) as the head of state and a prime minister as the head of government. The Je Khenpo is the head of the state religion, Vajrayana Buddhism.

The subalpine Himalayan mountains in the north rise from the country's lush subtropical plains in the south.[16] In the Bhutanese Himalayas, there are peaks higher than 7,000 metres (23,000 ft) above sea level. Gangkhar Puensum is Bhutan's highest peak and is the highest unclimbed mountain in the world. The wildlife of Bhutan is notable for its diversity,[17] including the Himalayan takin and golden langur. The capital and largest city is Thimphu, holding close to 15% of the population.

Bhutan and neighbouring Tibet experienced the spread of Buddhism, which originated in the Indian subcontinent during the lifetime of Gautama Buddha. In the first millennium, the Vajrayana school of Buddhism spread to Bhutan from the southern Pala Empire of Bengal. During the 16th century, Ngawang Namgyal unified the valleys of Bhutan into a single state. Namgyal defeated three Tibetan invasions, subjugated rival religious schools, codified the Tsa Yig legal system, and established a government of theocratic and civil administrators. Namgyal became the first Zhabdrung Rinpoche and his successors acted as the spiritual leaders of Bhutan, like the Dalai Lama in Tibet. During the 17th century, Bhutan controlled large parts of northeast India, Sikkim and Nepal; it also wielded significant influence in Cooch Behar State.[18] Bhutan ceded the Bengal Duars to British India during the Bhutan War in the 19th century. The House of Wangchuck emerged as the monarchy and pursued closer ties with Britain in the subcontinent. In 1910, a treaty guaranteed British advice in foreign policy in exchange for internal autonomy in Bhutan. The arrangement continued under a new treaty with India in 1949 (signed at Darjeeling) in which both countries recognised each other's sovereignty. Bhutan joined the United Nations in 1971. It has since expanded relations with 55 countries. While dependent on the Indian military, Bhutan maintains its own military units.

The 2008 Constitution established a parliamentary government with an elected National Assembly and a National Council. Bhutan is a founding member of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC). In 2020, Bhutan ranked third in South Asia after Sri Lanka and the Maldives in the Human Development Index, and 21st on the Global Peace Index as the most peaceful country in South Asia as of 2024, as well as the only South Asian country in the list's first quartile.[19][20] Bhutan is also a member of the Climate Vulnerable Forum, the Non-Aligned Movement, BIMSTEC, the IMF, the World Bank, UNESCO and the World Health Organization (WHO). Bhutan ranked first in SAARC in economic freedom, ease of doing business, peace and lack of corruption in 2016. Bhutan has one of the largest water reserves for hydropower in the world.[21][22] Melting glaciers caused by climate change are a growing concern in Bhutan.[23]

Etymology

[edit]The precise etymology of "Bhutan" is unknown, although it is likely to derive from the Tibetan endonym "Böd" for Tibet. Traditionally, it is taken to be a transcription of the Sanskrit Bhoṭa-anta (भोट-अन्त) "end of Tibet", a reference to Bhutan's position as the southern extremity of the Tibetan plateau and culture.[24][25][26]

Since the 17th century, Bhutan's official name has been Druk yul (literally, "country of the Drukpa Lineage" or "the Land of the Thunder Dragon," a reference to the country's dominant Buddhist sect); "Bhutan" appears only in English-language official correspondence.[26] The terms for the Kings of Bhutan, Druk Gyalpo ("Dragon King"), and the Bhutanese endonym Drukpa, "Dragon people," are similarly derived.[27]

Names similar to Bhutan—including Bohtan, Buhtan, Bottanthis, Bottan and Bottanter—began to appear in Europe around the 1580s. Jean-Baptiste Tavernier's 1676 Six Voyages is the first to record the name Boutan. However, these names seem to have referred not to modern Bhutan but to the Kingdom of Tibet. The modern distinction between the two did not begin until well into the Scottish explorer George Bogle's 1774 expedition. Realising the differences between the two regions, cultures, and states, his final report to the East India Company formally proposed calling the Druk Desi's kingdom "Boutan" and the Panchen Lama's kingdom "Tibet". The EIC's surveyor general James Rennell first anglicised the French name as "Bootan," and then popularised the distinction between it and Greater Tibet.[28]

The first time a separate Kingdom of Bhutan appeared on a western map, it did so under its local name "Broukpa".[28] Others include Lho Mon ("Dark Southland"), Lho Tsendenjong ("Southland of the Cypress"), Lhomen Khazhi ("Southland of the Four Approaches") and Lho Menjong ("Southland of the Herbs").[29][30]

History

[edit]

Stone tools, weapons, elephants, and remnants of large stone structures provide evidence that Bhutan was inhabited as early as 2000 BC, although there are no existing records from that time. Historians have theorised that the state of Lhomon (lit. 'southern darkness'), or Monyul ("Dark Land", a reference to the Monpa, an ethnic group in Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh, India), may have existed between 500 BC and AD 600. The names Lhomon Tsendenjong (Sandalwood Country) and Lhomon Khashi, or Southern Mon (country of four approaches), have been found in ancient Bhutanese and Tibetan chronicles.[31][32]

Buddhism was first introduced to Bhutan in the 7th century AD. The Tibetan king Songtsen Gampo[33] (reigned 627–649), a Buddhist convert, extended the Tibetan Empire into Sikkim and Bhutan.[34] He ordered the construction of two Buddhist temples, Bumthang in central Bhutan and Kyichu (near Paro) in the Paro Valley.[35] Buddhism was propagated in earnest[33] in 746[36] under King Sindhu Rāja (also Künjom;[37] Sendha Gyab; Chakhar Gyalpo), an exiled Indian king who had established a government in Bumthang at Chakhar Gutho Palace.[38]: 35 [39]: 13

Much of early Bhutanese history is unclear because most of the records were destroyed when fire ravaged the ancient capital, Punakha, in 1827. By the 10th century, Bhutan's religious history had a significant impact on its political development. Various subsects of Buddhism emerged that were patronized by the various Mongol warlords.

Bhutan may have been influenced by the Yuan dynasty with which it shares various cultural and religious similarities.

After the decline of the Yuan dynasty in the 14th century, these subsects vied with each other for supremacy in the political and religious landscape, eventually leading to the ascendancy of the Drukpa Lineage by the 16th century.[35][40]

Locally, Bhutan has been known by many names. The earliest Western record of Bhutan, the 1627 Relação of the Portuguese Jesuits Estêvão Cacella and João Cabral,[41] records its name variously as Cambirasi (among the Koch Biharis[42]), Potente, and Mon (an endonym for southern Tibet).[28] Until the early 17th century, Bhutan existed as a patchwork of minor warring fiefdoms, when the area was unified by the Tibetan lama and military leader Ngawang Namgyal, who had fled religious persecution in Tibet. To defend the country against intermittent Tibetan forays, Namgyal built a network of impregnable dzongs or fortresses, and promulgated the Tsa Yig, a code of law that helped to bring local lords under centralised control. Many such dzong still exist and are active centres of religion and district administration. Portuguese Jesuits Estêvão Cacella and João Cabral were the first recorded Europeans to visit Bhutan in 1627,[43] on their way to Tibet. They met Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal, presented him with firearms, gunpowder and a telescope, and offered him their services in the war against Tibet, but the Zhabdrung declined the offer. After a stay of nearly eight months Cacella wrote a long letter from the Chagri Monastery reporting on his travels. This is a rare extant report of the Zhabdrung.[44][45]

When Ngawang Namgyal died in 1651, his passing was kept secret for 54 years. After a period of consolidation, Bhutan lapsed into internal conflict. In 1711, Bhutan went to war against the Raja of the kingdom of Koch Bihar in the south. During the chaos that followed, the Tibetans unsuccessfully attacked Bhutan in 1714.[46]

In the 18th century, the Bhutanese invaded and occupied the kingdom of Koch Bihar. In 1772, the Maharaja of Koch Bihar appealed to the British East India Company which assisted by ousting the Bhutanese and later attacking Bhutan itself in 1774. A peace treaty was signed in which Bhutan agreed to retreat to its pre-1730 borders. However, the peace was tenuous, and border skirmishes with the British were to continue for the next hundred years. The skirmishes eventually led to the Duar War (1864–65), a confrontation to control of the Bengal Duars. After Bhutan lost the war, the Treaty of Sinchula was signed between British India and Bhutan. As part of the war reparations, the Duars were ceded to the United Kingdom in exchange for a rent of ₹50,000. The treaty ended all hostilities between British India and Bhutan.

During the 1870s, power struggles between the rival valleys of Paro and Tongsa led to civil war in Bhutan, eventually leading to the ascendancy of Ugyen Wangchuck, the penlop (governor) of Trongsa. From his power base in central Bhutan, Ugyen Wangchuck defeated his political enemies and united the country following several civil wars and rebellions during 1882–85.[47]

In 1907, an epochal year for the country, Ugyen Wangchuck was unanimously chosen as the hereditary king of the country by the Lhengye Tshog of leading Buddhist monks, government officials, and heads of important families, with the firm petition made by Gongzim Ugyen Dorji. John Claude White, British Political Agent in Bhutan, took photographs of the ceremony.[48] The British government promptly recognized the new monarchy. In 1910, Bhutan signed the Treaty of Punakha, a subsidiary alliance that gave the British control of Bhutan's foreign affairs and meant that Bhutan was treated as an Indian princely state. This had little real effect, given Bhutan's historical reticence, and also did not appear to affect Bhutan's traditional relations with Tibet. After the new Union of India gained independence from the United Kingdom on 15 August 1947, Bhutan became one of the first countries to recognise India's independence. On 8 August 1949, a treaty similar to that of 1910, in which Britain had gained power over Bhutan's foreign relations, was signed with the newly independent India.[31]

In 1953, King Jigme Dorji Wangchuck established the country's legislature—a 130-member National Assembly—to promote a more democratic form of governance. In 1965, he set up a Royal Advisory Council, and in 1968 he formed a Cabinet. In 1971, Bhutan was admitted to the United Nations, having held observer status for three years. In July 1972, Jigme Singye Wangchuck ascended to the throne at the age of sixteen after the death of his father, Dorji Wangchuck.

Bhutan's sixth Five-Year Plan (1987–92) included a policy of 'one nation, one people' and introduced a code of traditional Drukpa dress and etiquette called Driglam Namzhag. The dress element of this code required all citizens to wear the gho (a knee-length robe for men) and the kira (an ankle-length dress for women).[49] A central plank of the Bhutanese government's policy since the late 1960s has been to modernise the use of Dzongkha language. This began with abandoning the use of Hindi, a language that was adopted to help start formal secular education in the country, in 1964.[50] As a result, at the beginning of the school year in March 1990, the teaching of Nepali language (which share similarities with Hindi) spoken by ethnic Lhotshampas in southern Bhutan was discontinued and all Nepali curricular materials were discontinued from Bhutanese schools.[49]

In 1988, Bhutan conducted a census in southern Bhutan to guard against illegal immigration, a constant issue in the south where borders with India are porous.[51] Each family was required to present census workers with a tax receipt from the year 1958—no earlier, no later—or with a certificate of origin, which had to be obtained from one's place of birth, to prove that they were indeed Bhutanese citizens. Previously issued citizenship cards were no longer accepted as proof of citizenship. Alarmed by these measures, many began to protest for civil and cultural rights and demanded a total change to be brought to the political system that existed since 1907. As protests and related violence swept across southern Bhutan, the government in turn increased its resistance. People present at protests were labeled "anti-national terrorists".[52] After the demonstrations, the Bhutanese army and police began the task of identifying participants and supporters engaged in the violence against the state and people. They were arrested and held for months without trial.[49] Soon the Bhutanese government arbitrarily reported that its census operations had detected the presence in southern Bhutan of over 100,000 "illegal immigrants" although this number is often debated. The census operations, thus, were used as a tool for the identification, eviction and banishment of dissidents who were involved in the uprising against the state. Military and other security forces were deployed for forceful deportations of between 80,000 and 100,000 Lhotshampas and were accused of using widespread violence, torture, rape and killing.[53][54][55] The evicted Lhotshampas became refugees in camps in southern Nepal. Since 2008, many Western countries, such as Canada, Norway, the United Kingdom, Australia, and the United States, have allowed resettlement of the majority of the Lhotshampa refugees.[52]

Political reform and modernization

[edit]Bhutan's political system has recently changed from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional monarchy. King Jigme Singye Wangchuck transferred most of his administrative powers to the Council of Cabinet Ministers and allowed for impeachment of the King by a two-thirds majority of the National Assembly.[56]

In 1999, the government lifted a ban on television and internet, making Bhutan one of the last countries to introduce television. In his speech, the King said that television was a critical step to the modernisation of Bhutan as well as a major contributor to the country's gross national happiness,[57] but warned that the "misuse" of this new technology could erode traditional Bhutanese values.[58]

A new constitution was presented in early 2005. In December 2005, Wangchuck announced that he would abdicate the throne in his son's favour in 2008. On 9 December 2006, he announced that he would abdicate immediately. This was followed by the first national parliamentary elections in December 2007 and March 2008.

On 6 November 2008, 28-year-old Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck was crowned king.[59]

In July 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic, Bhutan became the first world-leading nation in its role of vaccinating 470,000 out of 770,000 people with a two-dose shot of AstraZeneca vaccines.

On 13 December 2023, Bhutan was officially delisted as a least developed country.[60]

Geography

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2017) |

Bhutan is on the southern slopes of the eastern Himalayas, landlocked between the Tibet Autonomous Region of China to the north and the Indian states of Sikkim, West Bengal, Assam to the west and south, and the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh to the east. It lies between latitudes 26°N and 29°N, and longitudes 88°E and 93°E. The land consists mostly of steep and high mountains crisscrossed by a network of swift rivers that form deep valleys before draining into the Indian plains. In fact, 98.8% of Bhutan is covered by mountains, which makes it the most mountainous country in the world.[61] Elevation rises from 200 m (660 ft) in the southern foothills to more than 7,000 m (23,000 ft). This great geographical diversity combined with equally diverse climate conditions contributes to Bhutan's outstanding range of biodiversity and ecosystems.[4]

Bhutan's northern region consists of an arc of Eastern Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows reaching up to glaciated mountain peaks with an extremely cold climate at the highest elevations. Most peaks in the north are over 7,000 m (23,000 ft) above sea level; the highest point is 7,570-metre (24,840 ft)-tall Gangkhar Puensum, which has the distinction of being the highest unclimbed mountain in the world.[62] The lowest point, at 98 m (322 ft), is in the valley of Drangme Chhu, where the river crosses the border with India.[62] Watered by snow-fed rivers, alpine valleys in this region provide pasture for livestock, tended by a sparse population of migratory shepherds.

The Black Mountains in Bhutan's central region form a watershed between two major river systems: the Mo Chhu and the Drangme Chhu. Peaks in the Black Mountains range between 1,500 and 4,925 m (4,921 and 16,158 ft) above sea level, and fast-flowing rivers have carved out deep gorges in the lower mountain areas. The forests of the central Bhutan mountains consist of Eastern Himalayan subalpine conifer forests in higher elevations and Eastern Himalayan broadleaf forests in lower elevations. The Woodlands of the central region provide most of Bhutan's forest production. The Torsa, Raidāk, Sankosh, and Manas are Bhutan's main rivers, flowing through this region. Most of the population lives in the central highlands.

In the south, the Sivalik Hills are covered with dense Himalayan subtropical broadleaf forests, alluvial lowland river valleys, and mountains up to around 1,500 m (4,900 ft) above sea level. The foothills descend into the subtropical Duars Plain, which is the eponymous gateway to strategic mountain passes (also known as dwars or dooars; literally, "doors" in Assamese, Bengali, Maithili, Bhojpuri, and Magahi languages).[16][63] Most of the Duars is in India, but a 10 to 15 km (6.2 to 9.3 mi)-wide strip extends into Bhutan. The Bhutan Duars is divided into two parts, the northern and southern Duars.

The northern Duars, which abut the Himalayan foothills, have rugged, sloping terrain and dry, porous soil with dense vegetation and abundant wildlife. The southern Duars have moderately fertile soil, heavy savanna grass, dense, mixed jungle, and freshwater springs. Mountain rivers, fed by melting snow or monsoon rains, empty into the Brahmaputra River in India. Data released by the Ministry of Agriculture showed that the country had a forest cover of 64% as of October 2005.

- Landscape of Bhutan

-

Gangkar Puensum, the highest mountain in Bhutan

-

Sub-alpine Himalayan landscape

-

A Himalayan peak from Bumthang

-

The Haa Valley in Western Bhutan

Climate

[edit]

Bhutan's climate varies with elevation, from subtropical in the south to temperate in the highlands and polar-type climate with year-round snow in the north. Bhutan experiences five distinct seasons: summer, monsoon, autumn, winter and spring. Western Bhutan has the heavier monsoon rains; southern Bhutan has hot humid summers and cool winters; central and eastern Bhutan are temperate and drier than the west with warm summers and cool winters.

Biodiversity

[edit]

Bhutan signed the Rio Convention on Biological Diversity on 11 June 1992, and became a party to the convention on 25 August 1995.[64] It has subsequently produced a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, with two revisions, the most recent of which was received by the convention on 4 February 2010.[65]

Animals

[edit]

Bhutan has a rich primate life, with rare species such as the golden langur.[66][67] A variant Assamese macaque has also been recorded, which is regarded by some authorities as a new species, Macaca munzala.[68]

The Bengal tiger, clouded leopard, hispid hare and the sloth bear live in the tropical lowland and hardwood forests in the south. In the temperate zone, grey langur, tiger, goral and serow are found in mixed conifer, broadleaf and pine forests. Fruit-bearing trees and bamboo provide habitat for the Himalayan black bear, red panda, squirrel, sambar, wild pig and barking deer. The alpine habitats of the great Himalayan range in the north are home to the snow leopard, blue sheep, Himalayan marmot, Tibetan wolf, antelope, Himalayan musk deer and the Bhutan takin, Bhutan's national animal. The endangered wild water buffalo occurs in southern Bhutan, although in small numbers.[69]

More than 770 species of bird have been recorded in Bhutan. The globally endangered white-winged duck has been added recently in 2006 to Bhutan's bird list.[70]

The 2010 BBC documentary Lost Land of the Tiger follows an expedition to Bhutan. The expedition is notable for claiming to obtain the first footage of tigers living at 4,000 metres (13,000 ft) in the high Himalayas. The BBC footage shows a female tiger lactating and scent-marking, followed a few days later by a male tiger responding, suggesting that the cats could be breeding at this elevation. Camera traps also recorded footage of other rarely seen forest creatures, including dhole (or Indian wild dog), Asian elephants, leopards and leopard cats.[71]

Plants

[edit]In Bhutan forest cover is around 71% of the total land area, equivalent to 2,725,080 hectares (ha) of forest in 2020, up from 2,506,720 hectares (ha) in 1990. In 2020, naturally regenerating forest covered 2,704,260 hectares (ha) and planted forest covered 20,820 hectares (ha). Of the naturally regenerating forest 15% was reported to be primary forest (consisting of native tree species with no clearly visible indications of human activity) and around 41% of the forest area was found within protected areas. For the year 2015, 100% of the forest area was reported to be under public ownership.[72][73]

More than 5,400 species of plants are found in Bhutan,[74] including Pedicularis cacuminidenta. Fungi form a key part of Bhutanese ecosystems, with mycorrhizal species providing forest trees with mineral nutrients necessary for growth, and with wood decay and litter decomposing species playing an important role in natural recycling.

Conservation

[edit]The Eastern Himalayas has been identified as a global biodiversity hotspot and counted among the 234 globally outstanding ecoregions of the world in a comprehensive analysis of global biodiversity undertaken by WWF between 1995 and 1997.

According to the Swiss-based International Union for Conservation of Nature, Bhutan is viewed as a model for proactive conservation initiatives. The Kingdom has received international acclaim for its commitment to the maintenance of its biodiversity.[75] This is reflected in the decision to maintain at least sixty per cent of the land area under forest cover, to designate more than 40%[76][77] of its territory as national parks, reserves and other protected areas, and most recently to identify a further nine per cent of land area as biodiversity corridors linking the protected areas. All of Bhutan's protected land is connected to one another through a vast network of biological corridors, allowing animals to migrate freely throughout the country.[78] Environmental conservation has been placed at the core of the nation's development strategy, the middle path. It is not treated as a sector but rather as a set of concerns that must be mainstreamed in Bhutan's overall approach to development planning and to be buttressed by the force of law. The country's constitution mentions environmental standards in multiple sections.[79]

Environmental issues

[edit]

Although Bhutan's natural heritage is still largely intact, the government has said that it cannot be taken for granted and that conservation of the natural environment must be considered one of the challenges that will need to be addressed in the years ahead.[80] Nearly 56.3% of all Bhutanese are involved with agriculture, forestry or conservation.[79] The government aims to promote conservation as part of its plan to target Gross National Happiness. It currently has net negative[78] greenhouse gas emissions because the small amount of pollution it creates is absorbed by the forests that cover most of the country.[81] While the entire country collectively produces 2,200,000 metric tons (2,200,000 long tons; 2,400,000 short tons) of carbon dioxide a year, the immense forest covering 72% of the country acts as a carbon sink, absorbing more than four million tons of carbon dioxide every year.[78] Bhutan had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 8.85/10, ranking it 16th globally out of 172 countries.[82]

Bhutan has a number of progressive environmental policies that have caused the head of the UNFCCC to call it an "inspiration and role model for the world on how economies and different countries can address climate change while at the same time improving the life of the citizen."[83] For example, electric cars have been pushed in the country and as of 2014[update] make up a tenth of all cars. Because the country gets most of its energy from hydroelectric power, it does not emit significant greenhouse gases for energy production.[81]

In practice, the overlap of these extensive protected lands with populated areas has led to mutual habitat encroachment. Protected wildlife has entered agricultural areas, trampling crops and killing livestock. In response, Bhutan has implemented an insurance scheme, begun constructing solar powered alarm fences, watch towers, and search lights, and has provided fodder and salt licks outside human settlement areas to encourage animals to stay away.[84]

The huge market value of the Ophiocordyceps sinensis fungus crop collected from the wild has also resulted in unsustainable exploitation which is proving very difficult to regulate.[85]

Bhutan has enforced a plastic ban rule from 1 April 2019, where plastic bags were replaced by alternative bags made of jute and other biodegradable material.[86]

Government and politics

[edit]

Bhutan is a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary form of government. The reigning monarch is Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck. The current Prime Minister of Bhutan is Tshering Tobgay, leader of the People's Democratic Party. Bhutan's democratic transition in 2008 is seen as an evolution of its social contract with the monarchy since 1907.[87] In 2019, Bhutan was classified in the Democracy Index as a hybrid regime alongside regional neighbours Nepal and Bangladesh. Minorities have been increasingly represented in Bhutan's government since 2008, including in the cabinet, parliament, and local government.[87]

The Druk Gyalpo (Dragon King) is the head of state.[88] The political system grants universal suffrage. It consists of the National Council, an upper house with 25 elected members; and the National Assembly with 47 elected lawmakers from political parties.

Executive power is exercised by the Council of Ministers led by the Prime Minister. Legislative power is vested in both the government and the National Assembly. Judicial power is vested in the courts. The legal system originates from the semi-theocratic Tsa Yig code, and was influenced by English common law during the 20th century. The chief justice is the administrative head of the judiciary.

Political culture

[edit]The first general elections for the National Assembly were held on 24 March 2008. The chief contestants were the Bhutan Peace and Prosperity Party (DPT) led by Jigme Thinley and the People's Democratic Party (PDP) led by Sangay Ngedup. The DPT won the elections, taking 45 out of 47 seats.[89] Jigme Thinley served as Prime Minister from 2008 to 2013.

The People's Democratic Party came to power in the 2013 elections. It won 32 seats and 54.88% of the vote. PDP leader Tshering Tobgay served as Prime Minister from 2013 to 2018.

Druk Nyamrup Tshogpa won the largest number of seats in the 2018 National Assembly election, bringing Lotay Tshering to the premiership and Druk Nyamrup Tshogpa into the government for the first time.[90]

Tshering Tobgay returned to power as Prime Minister after the 2024 election, with the PDP gaining 30 seats; he assumed office on 28 January 2024.[91]

Foreign relations

[edit]

In the early 20th century, Bhutan became a de facto protectorate of the British Empire under the Treaty of Punakha in 1910. British protection guarded Bhutan from Tibet and Qing China. In the aftermath of the Chinese Communist Revolution, Bhutan signed a friendship treaty with the newly independent Dominion of India in 1949. Its concerns were exacerbated after the annexation of Tibet by the People's Republic of China.[93]

Relations with Nepal remained strained due to Bhutanese refugees. Bhutan joined the United Nations in 1971. It was the first country to recognise Bangladesh's independence in 1971. It became a founding member of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) in 1985.[94] The country is a member of 150 international organisations,[93] including the Bay of Bengal Initiative, BBIN, World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the Group of 77.

Bhutan maintains strong economic, strategic, and military relations with India.[95][96] In February 2007, the Indo-Bhutan Friendship Treaty was substantially revised, clarifying Bhutan's full control of its foreign relations, as well as its independence and sovereignty. Whereas the Treaty of 1949, Article 2 stated: "The Government of India undertakes to exercise no interference in the internal administration of Bhutan. On its part the Government of Bhutan agrees to be guided by the advice of the Government of India in regard to its external relations," the revised treaty now states "In keeping with the abiding ties of close friendship and cooperation between Bhutan and India, the Government of the Kingdom of Bhutan and the Government of the Republic of India shall cooperate closely with each other on issues relating to their national interests. Neither government shall allow the use of its territory for activities harmful to the national security and interest of the other." The revised treaty also includes this preamble: "Reaffirming their respect for each other's independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity", an element absent in the earlier version. By long-standing agreement, Indian and Bhutanese citizens may travel to each other's countries without a passport or visa, but must still have their national identity cards. Bhutanese citizens may also work in India without legal restrictions.

Bhutan does not have formal diplomatic ties with China, but exchanges of visits at various levels between them have significantly increased in recent times. The first bilateral agreement between China and Bhutan was signed in 1998 and Bhutan has also set up honorary consulates in the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau.[97]

Bhutan's border with China is not mutually demarcated in some areas because China lays claims to those places. In 2021, after more than 35 years of border negotiations, China signed a memorandum of understanding with Bhutan to expedite those talks.[98] Approximately 269 square kilometres (104 sq mi) remain under discussion between China and Bhutan.[99] On 13 November 2005, Chinese soldiers crossed into the disputed territories between China and Bhutan and began building roads and bridges.[100] Bhutanese Foreign Minister Khandu Wangchuk took up the matter with Chinese authorities after the issue was raised in the Bhutanese parliament. In response, Foreign Ministry spokesman Qin Gang of the People's Republic of China said that the border remains in dispute and that the two sides are continuing to work for a peaceful and cordial resolution of the dispute, denying that the presence of soldiers in the area was an attempt to forcibly occupy it.[101] An Indian intelligence officer said that a Chinese delegation in Bhutan told the Bhutanese they were "overreacting". The Bhutanese newspaper Kuensel said that China might use the roads to further Chinese claims along the border.[100]

Bhutan has very warm relations with Japan, which provides significant development assistance. The Bhutanese royals were hosted by the Japanese imperial family during a state visit in 2011. Japan is also helping Bhutan cope with glacial floods by developing an early warning system. Bhutan enjoys strong political and diplomatic relations with Bangladesh. The Bhutanese king was the guest of honour during celebrations of the 40th anniversary of Bangladesh's independence.[102] A 2014 joint statement by the prime ministers of both countries announced cooperation in areas of hydropower, river management and climate change mitigation.[103] Bangladesh and Bhutan signed a preferential trade agreement in 2020 with provisions for free trade.[104]

Bhutan has diplomatic relations with 53 countries and the European Union and has missions in India, Bangladesh, Thailand, Kuwait, and Belgium. It has two UN missions, one in New York and one in Geneva. Only India, Bangladesh, and Kuwait have residential embassies in Bhutan. Other countries maintain informal diplomatic contact via their embassies in New Delhi and Dhaka. Bhutan maintains formal diplomatic relations with several Asian and European nations, Canada, and Brazil. Other countries, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, have no formal diplomatic relations with Bhutan but maintain informal contact through their respective embassies in New Delhi and with the United States through Bhutan's permanent mission to the United Nations. The United Kingdom has an honorary consul resident in Thimphu. The latest country Bhutan has established diplomatic relations with is Israel, on 12 December 2020.[105][106][107]

Bhutan opposed the Russian annexation of Crimea in United Nations General Assembly Resolution 68/262.

Military

[edit]

The Royal Bhutan Army is Bhutan's military service and is the weakest armed force in the world, in terms of Power Index, according to the Global Firepower survey.[108] It includes the royal bodyguard and the Royal Bhutan Police. Membership is voluntary and the minimum age for recruitment is 18.

The standing army numbers about 16,000 and is trained by the Indian Army.[109] It has an annual budget of about US$13.7 million (1.8 per cent of GDP). As a landlocked country, Bhutan has no navy. It also has no air force or army aviation corps. The Army relies on the Eastern Air Command of the Indian Air Force for air assistance.

Human rights

[edit]

Bhutan is ranked as "Partly Free" by Freedom House.[110] Bhutan's parliament decriminalised homosexuality in 2020.[111]

Women in Bhutan tend to be less active in politics than men due to customs and aspects of Bhutan's culture that dictate a woman's role in the household.[112] This leads to a limitation of their voices in government. Bhutan has made steps toward gender equality by enrolling more girls in school as well as creating the "National Commission for Women and Children" (NCWC) in 2004.[113] This programme was created to promote and protect women's and children's rights. Bhutan also elected its first female Dzongda, equivalent to a District Attorney, in 2012, and its first female minister in 2013.[113] Minister Dorji Choden, chair for the National Commission for Women and Children, believes that the aforementioned programme can be used to "promote women into more leadership roles" which can then lead women to take on more active roles in their society.[112] Overall there has also been a gradual increase in women in power with a 68% increase in women representation from 2011 to 2016.[113]

1990s ethnic cleansing

[edit]Starting in the 1980s, a part of Bhutan's minority population groups of Nepali speakers ("Lhotshampa"), in Southern Bhutan, fell victim to perceived political persecution by the Bhutanese government as part of what the Nepali-speaking population viewed as Bhutanisation (termed One Nation, One People) policy which was aimed to nationalise the country.[114][115] In 1977 followed by in 1985, Bhutan's government enacted legislations which impacted the Lhotshampa ethnic minority. The review of the national citizenship criteria and provisions for denationalisation of illegally present population in the country ensued.[116][117] The government enforced uniformity in dress, culture, tradition, language and literature to create a national identity which was aligned with the majority Drukpa culture of the country.[114][118][119][120] The Lhotshampas started demonstrations in protest of such discriminatory laws, voicing for a change to be brought to the existing political system toward a preferred multi-party democracy and to gain political autonomy for the Nepali Ethnic minority, most probably incited by the similar political uprising against the established monarchy in the neighbouring country of Nepal.[121] These demonstrations turned into violence when some ethnic Nepalese representatives were attacked by the government officials (armed forces) when schools in the southern districts were burned by the demonstrators.[122] Consequently, Bhutanese armed forces were mobilised; the members of Bhutanese police and army forces allegedly imprisoned some Nepali descendant ethnic minority who were suspected to be politically active in these demonstrations, under a command of then king Jigme Singye Wangchuck and home minister Dago Tshering to keep peace and open a line of communication.[123] Bhutan Armed forces were alleged to have targeted the Nepali ethnic southerners by burning down the houses, livestocks, and forced hundreds and thousands to be expelled from the country with their property being confiscated where no compensation were reported to be granted to anyone, however, claims to these were neither proved nor documented.[124]

This escalated up until the early 1990s, and was followed by the forceful expulsion of Nepali ethnic minority citizens from the southern part of Bhutan. The main purpose of this was the fear that revolt mirrored images of the Gorkhaland movement stirring up in the neighbouring state of West Bengal, and fueled fears of a fate similar to the Kingdom of Sikkim where the immigrant Nepalis population had overwhelmed the small native population of the kingdom, leading to its demise as an independent nation.[51] The Bhutanese security forces were accused of human rights violations including torture and rape of political demonstrators, and some Lhotshampas were accused of staging a violent revolt against the state.[117] According to the UNHCR, an estimate of 107,000 Bhutanese refugees living in seven camps in eastern Nepal have been documented as of 2008[update].[120] After many years in refugee camps, many inhabitants moved to other host nations such as Canada, Norway, the UK, Australia, and the US as refugees. The US admitted 60,773 refugees from fiscal years 2008 to 2012.[125]

The Nepalese government refused to assimilate the Bhutanese refugees (Lhotshampas) and did not allow a legal path to citizenship, so they were left stateless.[126] Careful scrutiny has been used to review the status of the refugee's relatives in the country, and citizenship identity cards and voting rights for these reviewed people are restricted.[126] Bhutan does not recognise political parties associated with these refugees and see them as a threat to the well-being of the country.[126] Human rights groups' rhetoric that the government interfered with individual rights by requiring all citizens, including ethnic minority members, to wear the traditional dress of the ethnic majority in public places was used as a political tool for the demonstrations. The Bhutanese government since then enforced the law of national attire to be worn in Buddhist religious buildings, government offices, schools, official functions, and public ceremonies aimed toward preserving and promoting the national identity of Bhutan.[126]

The kingdom has been accused of banning religious proselytising,[127] which critics deem as a violation of freedom of religion[128] and a policy of ethnic cleansing.[129] Starting in the 1980s, Bhutan adopted a policy of "One Nation One People" to create a unified sense of national identity. This was interpreted as cultural (in language, dress and religion) and political dominance of the majority Drukpa people by the Nepali-speaking people.[130] Inspired by the Gorkhaland Movement and fuelled by a sense of injustice, some Lhotshampas began organising demonstrations against the Bhutanese state. Furthermore, the removal of Nepali language in school curriculum to adopt a more centralised language in Dzongkha coupled with the denial of citizenship to those who were not able to prove officially issued land holding title prior to 1950[131] was perceived as specifically targeting Lhotshampa population estimated to be one-third of the population at the time.[132] This resulted in widespread unrest and political demonstrations.[116][133] In response to this threat, in 1988, the Bhutanese authorities carried out a special census[134] in southern Bhutan to review the status of legal residents from illegal immigrants. This region with high Lhotshampa population had to be legally verified, and the following census led to the deportation these Lhotshampas, estimated to be one-sixth of the total population at the time.[135][56][136] People who had been granted citizenship by the Bhutanese 1958 Nationality Law were also stripped of their citizenship. The state intervened after violence was instigated by some Nepali-speaking citizens in radical form of attacking government officials and burning of schools.[137] Members of Bhutanese police and army were accused of burning Lhotshampa houses, land confiscation and other widespread human rights abuses including arrest, torture and rape of Lhotshampas involved in political protests and violence.[117][138] Following forcible deportation from Bhutan, Lhotshampas spent almost two decades in refugee camps in Nepal and were resettled in various western countries such as the United States between 2007 and 2012.[139]

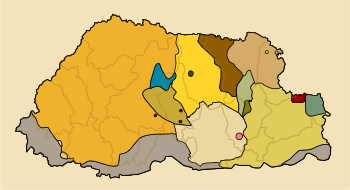

Political divisions

[edit]Bhutan is divided into twenty Dzongkhag (districts), administered by a body called the Dzongkhag Tshogdu. In certain thromdes (urban municipalities), a further municipal administration is directly subordinate to the Dzongkhag administration. In the vast majority of constituencies, rural gewog (village blocks) are administered by bodies called the Gewog Tshogde.[140]

Thromdes (municipalities) elect Thrompons to lead administration, who in turn represent the Thromde in the Dzongkhag Tshogdu. Likewise, geog elect headmen called gups, vice-headmen called mangmis, who also sit on the Dzongkhag Tshogdu, as well as other members of the Gewog Tshogde. The basis of electoral constituencies in Bhutan is the chiwog, a subdivision of gewogs delineated by the Election Commission.[140]

| Dzongkhags of the Kingdom of Bhutan | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| District | Dzongkha name | District | Dzongkha name |

| 1. Bumthang | བུམ་ཐང་རྫོང་ཁག་ | 11. Samdrup Jongkhar | བསམ་གྲུབ་ལྗོངས་མཁར་རྫོང་ཁག་ |

| 2. Chukha | ཆུ་ཁ་རྫོང་ཁག་ | 12. Samtse | བསམ་རྩེ་རྫོང་ཁག་ |

| 3. Dagana | དར་དཀར་ན་རྫོང་ཁག་ | 13. Sarpang | གསར་སྤང་རྫོང་ཁག་ |

| 4. Gasa | མགར་ས་རྫོང་ཁག་ | 14. Thimphu | ཐིམ་ཕུ་རྫོང་ཁག་ |

| 5. Haa | ཧཱ་རྫོང་ཁག་ | 15. Trashigang | བཀྲ་ཤིས་སྒང་རྫོང་ཁག་ |

| 6. Lhuntse | ལྷུན་རྩེ་རྫོང་ཁག་ | 16. Trashiyangtse | བཀྲ་ཤིས་གཡང་རྩེ་རྫོང་ཁག་ |

| 7. Mongar | མོང་སྒར་རྫོང་ཁག་ | 17. Trongsa | ཀྲོང་གསར་རྫོང་ཁག་ |

| 8. Paro | སྤ་རོ་རྫོང་ཁག་ | 18. Tsirang | རྩི་རང་རྫོང་ཁག་ |

| 9. Pemagatshel | པད་མ་དགའ་ཚལ་རྫོང་ཁག་ | 19. Wangdue Phodrang | དབང་འདུས་ཕོ་བྲང་རྫོང་ཁག་ |

| 10. Punakha | སྤུ་ན་ཁ་རྫོང་ཁག་ | 20. Zhemgang | གཞམས་སྒང་རྫོང་ཁག་ |

Economy

[edit]

Bhutan's currency is the ngultrum, whose value is fixed to the Indian rupee. The Indian rupee is also accepted as legal tender in the country. Though Bhutan's economy is one of the world's smallest,[142] it has grown rapidly in recent years, by eight per cent in 2005 and 14 per cent in 2006. In 2007, Bhutan had the second-fastest-growing economy in the world, with an annual economic growth rate of 22.4 per cent. This was mainly due to the commissioning of the gigantic Tala Hydroelectric Power Station. As of 2012[update], Bhutan's per capita income was US$2,420.[143]

Bhutan's economy is based on agriculture, forestry, tourism and the sale of hydroelectric power to India. Agriculture provides the main livelihood for 55.4 per cent of the population.[144] Agrarian practices consist largely of subsistence farming and animal husbandry. Handicrafts, particularly weaving and the manufacture of religious art for home altars, are a small cottage industry. A landscape that varies from hilly to ruggedly mountainous has made the building of roads and other infrastructure difficult and expensive.

This, and a lack of access to the sea, has meant that Bhutan has not been able to benefit from significant trading of its produce. Bhutan has no railways, though Indian Railways plans to link southern Bhutan to its vast network under an agreement signed in January 2005.[145] Bhutan and India signed a 'free trade' accord in 2008, which additionally allowed Bhutanese imports and exports from third markets to transit India without tariffs.[146] Bhutan had trade relations with the Tibet Autonomous Region of China until 1960, when it closed its border with China after an influx of refugees.[147]

Access to biocapacity in Bhutan is much higher than the world average. In 2016, Bhutan had 5.0 global hectares[148] of biocapacity per person within its territory, much more than the world average of 1.6 global hectares per person.[149] In 2016 Bhutan used 4.5 global hectares of biocapacity per person—their ecological footprint of consumption. This means they use less biocapacity than Bhutan contains. As a result, Bhutan is running a biocapacity reserve.[148]

The industrial sector is currently in a nascent stage. Although most production comes from cottage industry, larger industries are being encouraged and some industries such as cement, steel, and ferroalloy have been set up. Most development projects, such as road construction, rely on contract labour from neighbouring India. Agricultural produce includes rice, chilies, dairy (some yak, mostly cow) products, buckwheat, barley, root crops, apples, and citrus and maize at lower elevations. Industries include cement, wood products, processed fruits, alcoholic beverages and calcium carbide.

Bhutan has seen recent growth in the technology sector, in areas such as green tech and consumer Internet/e-commerce.[150] In May 2012, "Thimphu TechPark" was launched in the capital. It incubates startups via the "Bhutan Innovation and Technology Centre" (BITC).[151]

Incomes of over Nu 100,000 per year are taxed, but as Bhutan is currently one of the world's least developed countries, very few wage and salary earners qualify. Bhutan's inflation rate was estimated at three per cent in 2003. Bhutan has a gross domestic product of around US$5.855 billion (adjusted to purchasing power parity), making it the 158th-largest economy in the world. Per capita income (PPP) is around $7,641,[62] ranked 144th. Government revenues total $407.1 million, though expenditures amount to $614 million. Twenty-five per cent of the budget expenditure, however, is financed by India's Ministry of External Affairs.[152]

Bhutan's exports, principally electricity, cardamom, gypsum, timber, handicrafts, cement, fruit, precious stones and spices, total €128 million (2000 est.). Imports, however, amount to €164 million, leading to a trade deficit. Main items imported include fuel and lubricants, grain, machinery, vehicles, fabrics and rice. Bhutan's main export partner is India, accounting for 58.6 per cent of its export goods. Hong Kong (30.1 per cent) and Bangladesh (7.3 per cent) are the other two top export partners.[62] As its border with Tibet Autonomous Region is closed, trade between Bhutan and China is now almost non-existent. Bhutan's import partners include India (74.5 per cent), Japan (7.4 per cent) and Sweden (3.2 per cent).

Agriculture

[edit]

The share of the agricultural sector in GDP declined from approximately 55% in 1985 to 33% in 2003. In 2013 the government announced the aspiration that Bhutan will become the first country in the world with 100 per cent organic farming.[153][154] A decade later however this goal has proved elusive with just 1% of agricultural land having achieved organic status.[155]

Bhutanese red rice is the country's most widely known agricultural export, enjoying a market in North America and Europe. Bangladesh is the largest market of Bhutanese apples and oranges.[156]

Fishing in Bhutan is mainly centred on trout and carp.

Industry

[edit]The industrial sector accounts for 22% of the economy. The key manufacturing sectors in Bhutan include production of ferroalloy, cement, metal poles, iron and nonalloy steel products, processed graphite, copper conductors, alcoholic and carbonated beverages, processed fruits, carpets, wood products and furniture.[157] The production of ferrosilicon was pioneered by Damchae Dem, CEO of Pelden Group.[158]

Mining

[edit]Bhutan has deposits of numerous minerals. Commercial production includes coal, dolomite, gypsum, and limestone. The country has proven reserves of beryl, copper, graphite, lead, mica, pyrite, tin, tungsten, and zinc. However, the country's mineral deposits remain untapped, as it prefers to conserve the environment.[159]

Energy

[edit]

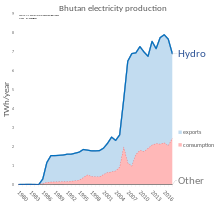

Bhutan's largest export is hydroelectricity. As of 2015[update], it generates about 2,000 MW of hydropower from dams in Himalayan river valleys.[160] The country has a potential to generate 30,000 MW of hydropower.[160] Power is supplied to various states in India. Future projects are being planned with Bangladesh.[160] Hydropower has been the primary focus for the country's five-year plans. As of 2015[update], the Tala Hydroelectric Power Station is its largest power plant, with an installed capacity of 1,020 MW. It has received assistance from India, Austria and the Asian Development Bank in developing hydroelectric projects.

Besides hydropower, it is also endowed with significant renewable energy resources such as solar, wind and bioenergy. Technically viable solar energy generation capacity is around 12,000 MW and wind around 760 MW. More than 70% of its land is under forest cover, which is an immense source of bioenergy in the country.[161]

Financial sector

[edit]

There are five commercial banks in the country and the two largest banks are the Bank of Bhutan and the Bhutan National Bank which are based in Thimphu. Other commercial banks are Bhutan Development Bank, T-Bank and Druk Punjab National Bank. The country's financial sector is also supported by other non-banking Financial Institutions. They are Royal Insurance Corporation of Bhutan (RICB), National Pension and Provident Fund (NPPF), and Bhutan Insurance Limited (BIL). The central bank of the country is the Royal Monetary Authority of Bhutan (RMA). The Royal Securities Exchange of Bhutan is the main stock exchange.

The SAARC Development Fund is based in Thimphu.[162]

Tourism

[edit]In 2014, Bhutan welcomed 133,480 foreign visitors.[163] Bhutan is a high-value destination. It imposes a daily sustainable development fee of US$100 a day on all nationals except Indians, Maldivians, and Bangladeshis.[164][165] Indians can apply for a permit to enter Bhutan which costs 1,200 INR per day (about US$14 in 2024). The industry employs 21,000 people and accounts for 1.8% of GDP.[166]

The country currently has no UNESCO World Heritage Sites, but it has eight declared tentative sites for UNESCO inclusion since 2012. These sites include: Ancient Ruin of Drukgyel Dzong,[167] Bumdelling Wildlife Sanctuary,[168] Dzongs: the centre of temporal and religious authorities (Punakha Dzong, Wangdue Phodrang Dzong, Paro Dzong, Trongsa Dzong and Dagana Dzong),[169] Jigme Dorji National Park (JDNP),[170] Royal Manas National Park (RMNP),[171] Sacred Sites associated with Phajo Drugom Zhigpo and his descendants,[172] Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary (SWS),[173] and Tamzhing Monastery.[174] Bhutan also has numerous tourist sites that are not included in its UNESCO tentative list. Bhutan has one element, the Mask dance of the drums from Drametse, registered in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List.[175]

Transport

[edit]

Air

[edit]Paro Airport is the only international airport in Bhutan. National carrier Drukair operates flights between Paro Airport and Bathpalathang Airport in Jakar (Bumthang Dzongkhag), central Bhutan, Gelephu Airport in Gelephu (Sarpang Dzongkhag) in the south and Yongphulla Airport in the east (Trashigang Dzongkhag) on a weekly basis.[176]

Road

[edit]The Lateral Road is Bhutan's primary east–west corridor, connecting the towns of Phuentsholing in the southwest to Trashigang in the east. Notable settlements that the Lateral Road runs through directly are Wangdue Phodrang and Trongsa. The Lateral Road also has spurs connecting to the capital Thimphu and other population centers such as Paro and Punakha. As with other roads in Bhutan, the Lateral Road presents serious safety concerns due to pavement conditions, sheer drops, hairpin turns, weather, and landslides.[177][178][179]

Since 2014, road widening has been a priority across Bhutan, in particular for the north-east–west highway from Trashigang to Dochula. The widening project is expected to be completed by the end of 2017 and will make road travel across the country substantially faster and more efficient. In addition, it is projected that the improved road conditions will encourage more tourism in the more inaccessible eastern region of Bhutan.[180][181][182] Currently, the road conditions appear to be deterring tourists from visiting Bhutan due to the increased instances of road blocks, landslides, and dust disruption caused by the widening project.[183]

Rail

[edit]Although Bhutan currently has no railways, it has entered into an agreement with India to link southern Bhutan to India's vast network by constructing an 18-kilometre-long (11 mi), 5 ft 6 in (1,676 mm) broad gauge rail link between Hasimara in West Bengal and Gelephu in Bhutan. The construction of the railway via Satali, Bharna Bari and Dalsingpara by Indian Railways will be funded by India.[184] Bhutan's nearest railway station is Hasimara. The planned Gelephu Green city will be linked by railway, connecting Indian state of Assam

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1960 | 224,000 | — |

| 1980 | 413,000 | +84.4% |

| 1990 | 536,000 | +29.8% |

| 1995 | 509,000 | −5.0% |

| 2005 | 650,000 | +27.7% |

| 2017 | 735,553 | +13.2% |

| Source:[185] | ||

Bhutan had a population of 777,486 people in 2021.[5][6] Bhutan has a median age of 24.8 years.[62] There are 1,070 males to every 1,000 females. The literacy rate in Bhutan is around 66%.[186]

Ethnic groups

[edit]

Bhutanese people primarily consist of the Ngalops and Sharchops, called the Western Bhutanese and Eastern Bhutanese respectively. Although the Sharchops are slightly larger in demographic size, the Ngalops dominate the political sphere, as the King and the political elite belong to this group.[187] The Ngalops primarily consist of Bhutanese living in the western part of the country. Their culture is closely related to that of Tibet. Much the same could be said of the Sharchops, the largest group, who traditionally follow the Nyingmapa rather than the official Drukpa Kagyu form of Tibetan Buddhism. In modern times, with improved transportation infrastructure, there has been much intermarriage between these groups.

The Lhotshampa, meaning "southerner Bhutanese", are a heterogeneous group of mostly Nepalese ancestry who have sought political and cultural recognition including equality in right to abode, language, and dress. Unofficial estimates claimed that they constituted 45% of the population in the 1988 census.[188] Starting in the 1980s, Bhutan adopted a policy of "One Nation One People" to exert cultural (in language, dress and religion) and political dominance of the majority Drukpa people.[130] The policy manifested in banning of teaching of Nepali language in schools and denial of citizenship to those who were not able to prove officially issued land holding title prior to 1950[131] specifically targeting ethnic Nepali-speaking minority groups ("Lhotshampa"), representing one-third of the population at the time.[132] This resulted in widespread unrest and political demonstrations.[116][133] In 1988, the Bhutanese authorities carried out a special census[134] in southern Bhutan, region of high Lhotshampa population, resulting in mass denationalisation of Lhotshampas, followed by forcible deportation of 107,000 Lhotshampas, approximately one-sixth of the total population at the time.[135][56][136] Those who had been granted citizenship by the 1958 Nationality Law were stripped of their citizenship. Members of Bhutanese police and army were involved in burning of Lhotshampa houses, land confiscation and other widespread human rights abuses including arrest, torture and rape of Lhotshampas involved in political protests.[117][138] Following forcible deportation from Bhutan, Lhotshampas spent almost two decades in refugee camps in Nepal and were resettled in various western countries such as the United States between 2007 and 2012.[139]

Cities and towns

[edit]- Thimphu, the largest city and capital of Bhutan.

- Damphu, the administrative headquarters of Tsirang District.

- Jakar, the administrative headquarters of Bumthang District and the place where Buddhism entered Bhutan.

- Mongar, the eastern commercial hub of the country.

- Paro, site of the international airport.

- Phuentsholing, Bhutan's commercial hub.

- Punakha, the old capital.

- Samdrup Jongkhar, the southeastern town on the border with India.

- Trashigang, administrative headquarters of Trashigang District, the most populous district in the country.

- Trongsa, in central Bhutan, which has the largest and the most magnificent of all the dzongs in Bhutan.

| Rank | Name | District | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Thimphu  Phuntsholing |

1 | Thimphu | Thimphu | 114,551 |  Paro | ||||

| 2 | Phuntsholing | Chukha | 27,658 | ||||||

| 3 | Paro | Paro | 11,448 | ||||||

| 4 | Gelephu | Sarpang | 9,858 | ||||||

| 5 | Samdrup Jongkhar | Samdrup Jongkhar | 9,325 | ||||||

| 6 | Wangdue Phodrang | Wangdue Phodrang | 8,954 | ||||||

| 7 | Punakha | Punakha | 6,626 | ||||||

| 8 | Jakar | Bumthang | 6,243 | ||||||

| 9 | Nganglam | Pemagatshel | 5,418 | ||||||

| 10 | Samtse | Samtse | 5,396 | ||||||

Religion

[edit]Religion in Bhutan (PewResearch) 2020[190][191]

It is estimated that between two-thirds and three-quarters of the Bhutanese population follow Vajrayana Buddhism, which is also the state religion. Hinduism accounts for less than 12% of the population.[192] The current legal framework in principle guarantees freedom of religion; proselytism, however, is forbidden by a royal government decision[192] and by judicial interpretation of the Constitution.[193]

Buddhism was introduced to Bhutan in 746 AD, when Guru Padmasambhava visited Bumthang District. Tibetan king Songtsän Gampo (reigned 627–649), a convert to Buddhism, ordered the construction of two Buddhist temples, at Bumthang in central Bhutan and at Kyichu Lhakhang (near Paro) in the Paro Valley.[35]

Languages

[edit]The national language is Dzongkha (Bhutanese), one of 53 languages in the Tibetan language family. The script, locally called Chhokey (literally, "Dharma language"), is identical to classical Tibetan. In Bhutan's education system, English is the medium of instruction, while Dzongkha is taught as the national language. Ethnologue lists 24 languages currently spoken in Bhutan, all of them in the Tibeto-Burman family, except Nepali, an Indo-Aryan language.[119]

Until the 1980s, the government sponsored the teaching of Nepali in schools in southern Bhutan. With the adoption of the Driglam Namzhag (Bhutanese code of etiquette) and its expansion into the idea of strengthening the role of Dzongkha, Nepali was dropped from the curriculum. The languages of Bhutan are still not well characterized, and several have yet to be recorded in an in-depth academic grammar. Before the 1980s, the Lhotshampa (Nepali-speaking community), mainly based in southern Bhutan, constituted approximately 30% of the population.[119] However, after a purge of Lhotshampas from 1990 to 1992 this number might not accurately reflect the current population.

Dzongkha is partially intelligible with Sikkimese and spoken natively by 25% of the population. Tshangla, the language of the Sharchop and the principal pre-Tibetan language of Bhutan, is spoken by a greater number of people. It is not easily classified and may constitute an independent branch of Tibeto-Burman. Nepali speakers constituted some 40% of the population as of 2006[update]. The larger minority languages are Dzala (11%), Limbu (10%), Kheng (8%), and Rai (8%). There are no reliable sources for the ethnic or linguistic composition of Bhutan, so these numbers do not add up to 100%.

Health

[edit]Bhutan has a life expectancy of 70.2 years (69.9 for males and 70.5 for females) according to the latest data for 2016 from the World Bank.[194][195]

Basic healthcare in Bhutan is free, as provided by the Constitution of Bhutan.[196]

Education

[edit]

Historically, education in Bhutan was monastic, with secular school education for the general population introduced in the 1960s.[197] The mountainous landscape poses barriers to integrated educational services.[197]

Today, Bhutan has two decentralised universities with eleven constituent colleges spread across the kingdom. These are the Royal University of Bhutan and the Khesar Gyalpo University of Medical Sciences of Bhutan, respectively. The first five-year plan provided for a central education authority—in the form of a director of education appointed in 1961—and an organised, modern school system with free and universal primary education.

Education programmes were given a boost in 1990, when the Asian Development Bank (see Glossary) granted a US$7.13 million loan for staff training and development, specialist services, equipment and furniture purchases, salaries and other recurrent costs, and facility rehabilitation and construction at Royal Bhutan Polytechnic.

Since the beginning of modern education in Bhutan, teachers from India—especially Kerala—have served in some of the most remote villages of Bhutan. Thus, 43 retired teachers who had served for the longest length of time were personally invited to Thimphu, Bhutan during the Teachers' Day celebrations in 2018, where they were honoured and individually thanked by His Majesty Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck. To celebrate 50 years of diplomatic relations between Bhutan and India, Bhutan's Education Minister, Jai Bir Rai, honoured 80 retired teachers who served in Bhutan at a special ceremony organised at Kolkata, India, on 6 January 2019.[198] Currently, there are 121 teachers from India placed in schools across Bhutan.

Culture

[edit]

Bhutan has a rich and unique cultural heritage that has largely remained intact because of its isolation from the rest of the world until the mid-20th century. One of the main attractions for tourists is the country's culture and traditions. Bhutanese tradition is deeply steeped in its Buddhist heritage.[199][200] Hinduism is the second most dominant religion in Bhutan, being most prevalent in the southern regions.[201] The government is increasingly making efforts to preserve and sustain the current culture and traditions of the country. Because of its largely unspoiled natural environment and cultural heritage, Bhutan has been referred to as The Last Shangri-La.[202]

While Bhutanese citizens are free to travel abroad, Bhutan is viewed as inaccessible by many foreigners. Another reason for it being an unpopular destination is the cost, which is high for tourists on tighter budgets. Entry is free for citizens of India, Bangladesh, and the Maldives, but all other foreigners are required to sign up with a Bhutanese tour operator and pay around US$250 per day that they stay in the country, though this fee covers most travel, lodging and meal expenses.[203] Bhutan received 37,482 visitor arrivals in 2011, of which 25% were for meetings, incentives, conferencing, and exhibitions.[204]

Bhutan was the first nation in the world to ban tobacco. It was illegal to smoke in public or sell tobacco, according to Tobacco Control Act of Bhutan 2010. Violators are fined the equivalent of $232—a month's salary in Bhutan. In 2021, this was reversed with the new Tobacco Control Act 2021 to allow for the import and sale of tobacco products to stamp out cross-border smuggling of tobacco products during the pandemic.[205]

Dress

[edit]The national dress for Bhutanese men is the gho, a knee-length robe tied at the waist by a cloth belt known as the kera. Women wear an ankle-length dress, the kira, which is clipped at the shoulders with two identical brooches called the koma and tied at the waist with kera. An accompaniment to the kira is a long-sleeved blouse, the "wonju", which is worn underneath the kira. A long-sleeved, jacket-like garment called the "toego" is worn over the kira. The sleeves of the wonju and the tego are folded together at the cuffs, inside out. Social status and class determine the textures, colours, and decorations that embellish the garments.[206]

Jewellery is commonly worn by women, especially during religious festivals ("tsechus") and public gatherings. To strengthen Bhutan's identity as an independent country, Bhutanese law requires all Bhutanese government employees to wear the national dress at work and all citizens to wear the national dress while visiting schools and other government offices, though many citizens, particularly adults, choose to wear the customary dress as formal attire.

Varicolored scarves, known as rachu for women and kabney for men, are important indicators of social standing, as Bhutan has traditionally been a feudal society; in particular, red is the most common colour worn by women. The "Bura Maap" (Red Scarf) is one of highest honours a Bhutanese civilian can receive. It, as well as the title of Dasho, comes from the throne in recognition of an individual's outstanding service to the nation.[207] On previous occasions, the King himself conferred Bura Maaps to outstanding individuals such as the Director General of Department Hydropower and Power System, Yeshi Wangdi, the Deputy Chairperson of National Council, Dasho Dr. Sonam Kinga, and former National Assembly Speaker, Dasho Ugyen Dorji.[208]

Architecture

[edit]

Bhutanese architecture remains distinctively traditional, employing rammed earth and wattle and daub construction methods, stone masonry, and intricate woodwork around windows and roofs. Traditional architecture uses no nails or iron bars in construction.[44][209][210] Characteristic of the region is a type of castle fortress known as the dzong. Since ancient times, the dzongs have served as the religious and secular administrative centers for their respective districts.[211] The University of Texas at El Paso in the United States has adopted Bhutanese architecture for its buildings on campus, as have the nearby Hilton Garden Inn and other buildings in the city of El Paso.[212]

Public holidays

[edit]Bhutan has numerous public holidays, most of which coincide with traditional, seasonal, secular or religious festivals. They include the winter solstice (around 1 January, depending on the lunar calendar),[213] Lunar New Year (February or March),[214] the King's birthday and the anniversary of his coronation, the official end of monsoon season (22 September),[215] National Day (17 December),[216] and various Buddhist and Hindu celebrations.

Media

[edit]Film industry

[edit]Music and dance

[edit]

Dance dramas and masked dances such as the Cham dance are common traditional features at festivals, usually accompanied by traditional music. At these events, dancers depict heroes, demons, dæmons, death heads, animals, gods, and caricatures of common people by wearing colourful wooden or composition face masks and stylised costumes. The dancers enjoy royal patronage, and preserve ancient folk and religious customs and perpetuate the ancient lore and art of mask-making.

The music of Bhutan can generally be divided into traditional and modern varieties; traditional music comprises religious and folk genres, the latter including zhungdra and boedra.[217] The modern rigsar is played on a mix of traditional instruments and electronic keyboards, and dates back to the early 1990s; it shows the influence of Indian popular music, a hybrid form of traditional and Western popular influences.[218][219]

Family structure

[edit]In Bhutanese families, inheritance generally passes matrilineally through the female rather than the male line. Daughters will inherit their parents' house. A man is expected to make his own way in the world and often moves to his wife's home. Love marriages are more common in urban areas, but the tradition of arranged marriages among acquainted families is still prevalent in most of the rural areas. Although uncommon, polygamy is accepted, often being a device to keep property in a contained family unit rather than dispersing it.[220] The previous king, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, who abdicated in 2006, had four queens, all of whom are sisters. The current king, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, wed Jetsun Pema, then 21, a commoner and daughter of a pilot, on 13 October 2011.

Cuisine

[edit]

Rice (red rice), buckwheat, and increasingly maize, are the staples of Bhutanese cuisine. The local diet also includes pork, beef, yak meat, chicken, and lamb. Soups and stews of meat and dried vegetables spiced with chilies and cheese are prepared. Ema datshi, made very spicy with cheese and chilies, might be called the national dish for its ubiquity and the pride that Bhutanese have for it. Dairy foods, particularly butter and cheese from yaks and cows, are also popular, and indeed almost all milk is turned into butter and cheese. Popular beverages include butter tea, black tea, locally brewed ara (rice wine), and beer.[44]

Sports

[edit]

Bhutan's national and most popular sport is archery.[221] Competitions are held regularly in most villages. It differs from Olympic standards in technical details such as the placement of the targets and atmosphere. Two targets are placed over 100 metres (330 ft) apart, and teams shoot from one end of the field to the other. Each member of the team shoots two arrows per round. Traditional Bhutanese archery is a social event, and competitions are organised between villages, towns, and amateur teams. There is usually plenty of food and drink complete with singing and dancing. Attempts to distract an opponent include standing around the target and making fun of the shooter's ability. Darts (khuru) is an equally popular outdoor team sport, in which heavy wooden darts pointed with a 10 cm (3.9 in) nail are thrown at a paperback-sized target 10 to 20 metres (33 to 66 ft) away.

Another traditional sport is the Digor, which resembles the shot put and horseshoe throwing.

Another popular sport is football.[221] In 2002, Bhutan's national football team played Montserrat, in what was billed as The Other Final; the match took place on the same day Brazil played Germany in the World Cup final, but at the time Bhutan and Montserrat were the world's two lowest ranked teams. The match was held in Thimphu's Changlimithang National Stadium, and Bhutan won 4–0. A documentary of the match was made by the Dutch filmmaker Johan Kramer. In 2015, Bhutan won its first two FIFA World Cup Qualifying matches, beating Sri Lanka 1–0 in Sri Lanka and 2–1 in Bhutan.[222] Cricket has also gained popularity in Bhutan, particularly since the introduction of television channels from India. The Bhutan national cricket team is one of the most successful affiliate nations in the region.[citation needed]

Women in the workforce

[edit]Women have begun to participate more in the work force and their participation is one of the highest in the region.[113] However, the unemployment rates among women are still higher than those of men and women are in more unsecure work fields, such as agriculture.[223] Most of the work that women do outside of the home is in family-based agriculture which is insecure and is one of the reasons why women are falling behind men when it comes to income.[113] Women also, in general, work lower-quality jobs than men and only earn 75% of men's earnings.[224]

Women in the household

[edit]Rooted deep in Bhutan culture is the idea of selflessness and the women of Bhutan take on this role in the context of the household.[225] Nearly 1/4 of all women have reported experiencing some form of violence from their husband or partner.[223] Some Bhutanese communities have what is referred to as matrilineal communities, where the eldest daughter receives the largest share of the land.[224] This is due to the belief that she will stay and take care of her parents while the son will move out and work to get his own land and for his own family.[224] Importantly, land ownership does not necessarily equate to economic benefits – despite the eldest daughter having control of the house, it is the husband that is in charge of making decisions.[224] However, the younger generation has stepped away from this belief, in splitting the land evenly between the children instead of the eldest daughter inheriting the most land.[224]

Women's health

[edit]Throughout Bhutan, there has been an improvement in reproductive health services that has led to a drastic drop in maternal mortality rate, dropping from 1,000 in 1990 to 180 in 2010.[224][clarification needed] There has also been an increase in contraceptive use from less than 1/3 in 2003 to 2/3 in 2010.[224]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Pew Research Center – Global Religious Landscape 2010 – religious composition by country" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2016.

- ^ "Bhutan, Religion And Social Profile | National Profiles | International Data". Thearda.com. Archived from the original on 17 July 2022. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "9th Five Year Plan (2002–2007)" (PDF). Royal Government of Bhutan. 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- ^ a b "National Portal of Bhutan". Department of Information Technology, Bhutan. Archived from the original on 23 April 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- ^ a b "World Population Prospects 2022". United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ a b "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100" (XSLX) ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "Bhutan". City Population. Archived from the original on 5 October 2003. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Bhutan)". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Archived from the original on 30 October 2023. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ^ "Gini Index". World Bank. Archived from the original on 9 February 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/2024" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2024. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ "List of left- & right-driving countries". WorldStandards. Archived from the original on 10 November 2022. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ "Treaty Bodies Database – Document – Summary Record – Bhutan". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR). 5 June 2001. Archived from the original on 10 January 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2009.

- ^ "World Population Prospects". United Nations. 2008. Archived from the original on 7 January 2010. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- ^ Driem, George van (1998). Dzongkha = Rdoṅ-kha. Leiden: Research School, CNWS. p. 478. ISBN 978-90-5789-002-4.