Domingo Cavallo

Domingo Cavallo | |

|---|---|

Cavallo in 2001 | |

| Minister of Economy | |

| In office 20 March 2001 – 20 December 2001 | |

| President | Fernando de la Rúa |

| Preceded by | Ricardo López Murphy |

| Succeeded by | Jorge Capitanich |

| In office 1 February 1991 – 6 August 1996 | |

| President | Carlos Menem |

| Preceded by | Antonio Erman González |

| Succeeded by | Roque Fernández |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office July 8, 1989 – January 31, 1991 | |

| President | Carlos Menem |

| Preceded by | Susana Ruiz Cerruti |

| Succeeded by | Guido di Tella |

| President of the Central Bank of Argentina | |

| In office July 2, 1982 – August 26, 1982 | |

| President | Reynaldo Bignone |

| Preceded by | Egidio Iannella |

| Succeeded by | Julio González del Solar |

| National Deputy | |

| In office December 10, 1997 – March 20, 2001 | |

| Constituency | City of Buenos Aires |

| In office December 10, 1987 – December 10, 1989 | |

| Constituency | Cordoba |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Domingo Felipe Cavallo July 21, 1946 San Francisco, Córdoba, Argentina |

| Political party | Justicialist Party (1983–1996) Action for the Republic (1996–2005) Is Possible Party (2013) |

| Spouse | Sonia Abrazián |

| Alma mater | National University of Córdoba Harvard University |

| Website | Official website |

Domingo Felipe Cavallo (born July 21, 1946) is an Argentine economist and politician. Between 1991 and 1996, he was the Minister of Economy during Carlos Menem's presidency. He is known for implementing the convertibility plan, which established a pseudo-currency board with the United States dollar and allowed the dollar to be used for legal contracts. This brought the inflation rate down from over 1,300% in 1990 to less than 20% in 1992 and nearly to zero during the rest of the 1990s.[1] He implemented pro-market reforms which included privatizations of state enterprises. Productivity per hour worked during his five-years as minister of Menem increased by more than 100%.[2] In 2001, he was the economy minister for nine months during the 1998–2002 Argentine great depression. During a bank run, he implemented a restriction on cash withdrawing, known as corralito. This was followed by the December 2001 riots in Argentina and the fall of Fernando de la Rúa as president.[3]

Cavallo is a Doctor in Economic Sciences from the National University of Córdoba and obtained his PhD in Economics from Harvard University. He received five Honoris Causa doctorates from Genoa, Turin, Bologna, Ben-Gurion and Paris Pantheon-Sorbonne universities. He was professor at the National and Catholic Universities of Córdoba, and at New York, Harvard, and Yale universities.[4]

Early years

[edit]Cavallo was born in San Francisco, Córdoba Province to Florencia and Felipe Cavallo, Italian Argentine immigrants from the Piedmont Region. He graduated with honors in Accounting (1967) and Economics (1968) at the National University of Córdoba, where he earned his doctorate in economics in 1970. He married the former Sonia Abrazián in 1968, and had three children. He would later enroll at Harvard University, where he earned a second doctorate in Economics in 1977.[5]

Cavallo taught at the National University of Córdoba (1969–84), the Catholic University of Córdoba (1970–74), and New York University (1996–97). He wrote a number of books and was publisher of Forbes in 1998–99.

Central Bank

[edit]In July 1982, after the Falklands War fiasco brought more moderate leadership to the military dictatorship, Cavallo was appointed president of the Central Bank. He inherited the country's most acute financial and economic crisis since 1930, and a particularly heinous Central Bank regulation painfully remembered as the Central Bank Circular 1050.

Implemented in 1980 at the behest of conservative Minister of Economy, José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz, policy tied adjustable loan installments (nearly all lending in Argentina is on an adjustable interest basis) to the value of the US dollar locally. Exchange rates were controlled at the time and therefore raised little concern. The next February, however, the peso was sharply devalued and continued to plummet for the rest of 1981 and into 1982. Mortgage and business borrowers saw their monthly installments increase over tenfold in just a year and many, including homeowners just months away from paying off their loans, unable to keep up, either lost their entire equity or everything outright.[6]

Cavallo immediately rescinded the hated Circular 1050 and as a result, saved millions of homeowners and small-business owners from financial ruin (as well as millions more, indirectly). What followed, however, remained the subject of great controversy.[7]

Though nothing new to the economic history of Argentina, he is often accused of implementing financial policies that may have allowed Argentina's main private enterprises to transfer their debts to the state, transforming their private debt into public obligations. During 1982 and 1983, more than 200 firms (30 economic groups and 106 transnational enterprises) transferred a great part of their 17 billion dollar debt to the federal government, thanks to secured exchange rates on loan installments. This fraud took place both before and after his very brief turn at the Central Bank, but not while he was in charge. In a speech in September 1982 he was forced renounce and express his opposition to the transfer of debt to the state. He inherited this practice from Martínez de Hoz himself (whose chief interest, steelmaker Acindar, had unloaded US$700 million of its debts in this way). Moreover, Cavallo subjected payments covered by these exchange rate guarantees to indexation; this latter stipulation was dropped by his successor, Julio González del Solar.[8][9]

Beginnings in politics

[edit]

His involvement in politics began when he was elected as a student representative to the highest government body of the Economics School (1965–1966). He acted as Undersecretary of Development of the provincial government (1969–1970), director (1971–1972) and vice chairman of the board (1972–1973) of the Provincial Bank and Undersecretary of Interior of the national government.

This controversy notwithstanding, upon Argentina's return to democracy in December 1983, he became a close economic advisor to Peronist politician José Manuel de la Sota and was elected as a Peronist deputy for Córdoba Province in the 1987 mid-term polls.

Drawing from his Fundación Mediterránea think-tank, he prepared an academic team for taking over the management of the economy, and to that end he participated actively in Carlos Menem's bid for the presidency in 1989. President Alfonsín's efforts to control hyperinflation (which reached 200% a month in July 1989) failed, and led to food riots and Alfonsín's resignation.

Minister of Foreign relations

[edit]

As Foreign Minister, in 1989 he met with British Foreign Secretary John Major, this being the first such meeting since the end of the Falklands War seven years earlier.[10]

As Menem initially chose to deliver the Economy Ministry to senior executives of the firm Bunge y Born, Cavallo had to wait a few more years to put his economic theories into practice. He served as Menem's foreign minister, and was instrumental in the realignment of Argentina with the Washington Consensus advanced by U.S. President George H. W. Bush. Finally, after several false starts, and two further peaks of hyperinflation, Menem put Cavallo at the helm of the Argentine Economy Ministry in February, 1991.

Minister of Economy at the Menem administration

[edit]

In May 1989, amid the worst economic crisis in the country's history, Carlos Menem was elected President of Argentina.[11]

Hyperinflation forced him to abandon peronist orthodoxy in favour of a fiscally conservative, market-oriented economic policy.[11]

Domingo Cavallo was appointed in 1991, and deepened the liberalization of the economy. He liberalized trade (by removing export taxes and reducing import duties, removing non-tariff barriers to imports, and removing restrictions on foreign investment).[12]

He reformed the State and recreated a market economy based on a reduction in public spending and the fiscal deficit (through the privatization of state companies; the elimination of price controls, wage controls and currency controls; and the elimination of trade subsidies).[13]

He reformed the tax policy to simplify taxes and reduce non-social government spending, and reached an agreement with the International Monetary Fund to achieve the path towards adherence to a Brady Plan a plan about the debt restructuring.

These reforms were a success: the capital flights ended, interest rates were lowered, inflation fell to single digits, and economic activity increased; in that year alone, the gross domestic product grew at a rate of 10,5%.[14][15]

He was the ideologist behind the Convertibility Plan, which created a currency board that fixed the dollar-peso exchange rate at 1 peso per US dollar; he signed his plan into law on April 1, 1991. Cavallo thus succeeded in defeating inflation, which had averaged over 220% (1975–1988), had leapt to 5000% (1989) and remained at 1300% (1990).[16]

President Menem had already privatized the state telecom concern and national airlines (the once-premier airline in Latin America, Aerolíneas Argentinas, which was later almost run into the ground). The stability Cavallo's plan helped bring about, however, opened prospects for more privatizations than ever. Going on to total over 200 state enterprises, these included: the costly state railroads concern, the state oil monopoly Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales, several public utilities, two government television stations, 10,000 km (6000 mi) of roads, steel and petrochemical firms, grain elevators, hotels, subways and even racetracks. A panoply of provincial and municipal banks were sold to financial giants abroad (sometimes over the opposition of their respective governors and mayors) and, taking a page from the Chile pension system privatization, the mandatory National Pension System was opened to choice through the authorization of private pension schemes.[17]

GDP, long stuck at its 1973 level even with a growing population, grew by about a third from early 1991 to late 1994. Fixed investment, depressed since the 1981–82 crisis, more than doubled during this period.

Consumers also benefited: income poverty fell by about half (to under 20%) and new auto sales (likewise depressed since 1982) jumped fivefold, to about 500,000 units. This boom, however, had its problems early on. Tight federal budgets kept the budget deficits of the provinces from improving and, though many benefited from Cavallo's insistence that large employers translate higher productivity into higher pay, this same productivity boom (as well as the nearly 200,000 layoffs the privatizations caused) helped unemployment jump from about 7% in 1991–92 to over 12%, by 1994.

The 1995 Mexican Crisis shocked consumer and business confidence and ratcheted joblessness to 18% (the highest since the 1930s). Confidence and the economy recovered relatively quickly; but, the consequences of double-digit unemployment soon created a crime wave that to some extent continues to this day. Unemployment and poverty eased only very slowly after the return to growth in early 1996.

Independent

[edit]

In mid-1995, Cavallo denounced the existence of presumed "mafias" entrenched within the circles of power. After his first public accusations, relations between Cavallo, President Menem and his colleagues became progressively strained.

In 1996, shortly after Menem's reelection, the flux of money from privatisation ceased, and Cavallo was ousted from the cabinet, due to his volatile personality and fights with other cabinet members, coupled with staggering unemployment and social unrest caused by his economic policies and the Mexican crisis. Following months of speculation, Menem asked for his resignation on July 26, 1996.[18]

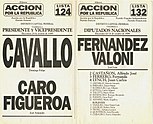

Cavallo founded a political party, Action for the Republic, which allowed him to return to Congress since 1997, this time as a National Deputy for the City of Buenos Aires.

Cavallo ran for president in 1999, but was defeated by Fernando de la Rúa. Cavallo came in third place and received 11% of the vote, far behind both de la Rúa and the other main candidate, Peronist Eduardo Duhalde.

He also ran for Mayor of Buenos Aires in 2000, got second place and lost to Aníbal Ibarra.

Minister of Economy with de la Rúa and during the crisis

[edit]

Cavallo was called by President de la Rúa in March 2001 to lead the economy once again, in the face of a weakened coalition government and two years of recession.[19]

He attempted to restore business confidence by renegotiating the external debt with the International Monetary Fund and with bondholders, but the growing country risk and spiraling put options by large investors and foreign holdings led to a bank run and a massive capital flight. In late November 2001, Cavallo introduced a set of measures that blocked the usage of cash, informally known as the corralito ("financial corral"). The anger of those Argentines with the means to invest abroad created a framework for the popular middle-class protest termed the cacerolazo.

Political pressure by the Peronist opposition and other organized economic interests coincided with the December 2001 riots. This critical situation finally forced Cavallo, and then de la Rúa, to resign.[20]

A series of Peronist presidents came and left in the next few days, until Eduardo Duhalde, the opponent of De la Rua and Cavallo in the 1999 presidential election, took power on January 2, 2002. Soon afterwards the government decreed the end of peso-dollar convertibility, devalued the peso and soon afterwards let it float, which led to a swift depreciation (the exchange rate briefly reached 4 pesos per dollar in July 2002) and inflation (about 40% in 2002).

Cavallo's policies are viewed by opponents as major causes of the deindustrialization and the rise of unemployment, poverty and crime endured by Argentina in the late 1990s, as well as the collapse of 2001, the ensuing default of the Argentine public debt.

After the crisis

[edit]

Between April and June 2002, Cavallo was jailed for alleged participation in illegal weapons sales during the Menem administration. He was exonerated of all charges related to this scandal in 2005.[21]

Cavallo served as the Robert Kennedy Visiting Professor in Latin American Studies in the department of economics at Harvard University from 2003 to 2004.

He has also continued to serve as a member of the influential Washington-based financial advisory body, the Group of Thirty.

As of January 2012, Cavallo is a senior fellow at the Jackson Institute for Global Affairs at Yale University as well as a visiting lecturer at Yale's economics department.

Cavallo returned to Córdoba Province in 2013 to run for Chamber of Deputies under the Es Posible ticket, led by center-right Peronist Alberto Rodríguez Saá.[22] Winning only 1.28% of the provincial vote, Cavallo failed to reach the required 1.5% threshold in the primaries elections, and was disqualified from the running for the general election in what the local press described as "an emphatic defeat."[23]

Criminal sentence

[edit]On December 1, 2015, Cavallo, ex president Carlos Saul Menem, and ex justice minister Raúl Granillo Ocampo, were found guilty of embezzlement by the court Tribunal Oral Federal 4.[24][25]

Honour

[edit]Foreign honour

[edit] Malaysia : Honorary Commander of the Order of the Defender of the Realm (P.M.N.) (1994)[26]

Malaysia : Honorary Commander of the Order of the Defender of the Realm (P.M.N.) (1994)[26]

References

[edit]- ^ Graciela Kaminsky; Amine Mati; Nada Choueiri (November 2009). "Thirty Years of Currency Crises in Argentina External Shocks or Domestic Fragility?" (PDF). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- ^ a b Our World in Data based on Feenstra, Robert C., Robert Inklaar and Marcel P. Timmer (2015), "The Next Generation of the Penn World Table" American Economic Review, 105(10), 3150-3182, available for download at www.ggdc.net/pwt. PWT v9.1

- ^ "Argentina's collapse - A decline without parallel". The Economist. February 28, 2002.

- ^ "Domingo Cavallo: biography". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Noticias. 12 September 1991.

- ^ "El recuerdo de la Circular 1050". Clarín. April 14, 2002.

- ^ "Ordenan investigar si Cavallo debe devolver 17.000 millones de dólares". La Nación. September 16, 2011.

- ^ Cavallo, Domingo. Economía en Tiempos de Crisis. p. 25.

- ^ Argentina: From Insolvency to Growth. World Bank, 1993.

- ^ John Major (1999). John Major: The Autobiography. Harper Collins. p. 123.

- ^ a b "Carlos Menem | Biography & Facts".

- ^ Starr, Pamela K. (1997). "Government Coalitions and the Viability of Currency Boards: Argentina under the Cavallo Plan". Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs. 39 (2): 83–133. doi:10.2307/166512. JSTOR 166512.

- ^ "Server Error" (PDF).

- ^ "Finance and Development".

- ^ Saxton, Jim (June 2003). "ARGENTINA'S ECONOMIC CRISIS: CAUSES AND CURES" (PDF). United States Congressional Joint Economic Committee.

- ^ "INDEC: consumer prices". Archived from the original on June 19, 2009. Retrieved June 12, 2009.

- ^ Cavallo, Domingo; Runde, Sonia Cavallo (2017). Argentina's Economic Reforms of the 1990s in Contemporary and Historical Perspective. Routledge. ISBN 978-1857438048.

- ^ Clarín. 27 July 1996 (in Spanish)

- ^ La Nación. 20 March 2001 Archived 25 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish)

- ^ La Nación. 20 December 2001 Archived 5 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish)

- ^ "Alivio para Menem y Cavallo en causa por contrabando de armas". La Crónica de Hoy. April 13, 2005. Archived from the original on August 6, 2016. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ^ "Unos regresaron con gloria; otros fracasaron". La Nación. August 13, 2013.

- ^ "Cavallo no llega a octubre en una elección cordobesa dominada por Schiaretti". La Prensa.

- ^ "Condenaron a Menem y Cavallo por el pago de sobresueldos".

- ^ "Condenan a prisión a Menem y a Cavallo por pagar sobresueldos, pero seguirán libres". Archived from the original on December 3, 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ^ "Semakan Penerima Darjah Kebesaran, Bintang dan Pingat". Archived from the original on July 19, 2019. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

External links

[edit]- Personal homepage (in Spanish and English)

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- 1946 births

- Living people

- Group of Thirty

- Argentine people of Italian descent

- People from Córdoba Province, Argentina

- National University of Córdoba alumni

- Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences alumni

- Members of the Argentine Chamber of Deputies elected in Buenos Aires

- Members of the Argentine Chamber of Deputies elected in Córdoba

- Presidents of the Central Bank of Argentina

- Foreign ministers of Argentina

- Argentine economists

- Ministers of economy of Argentina

- Argentine anti-communists

- Candidates for President of Argentina

- Justicialist Party politicians

- Action for the Republic politicians

- Argentine politicians convicted of corruption