Barry Sheene

| Barry Sheene MBE | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

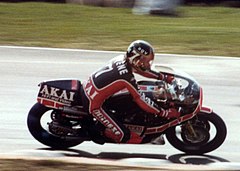

Sheene in 1975 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | British | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 11 September 1950 London, England | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 10 March 2003 (aged 52) Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Barry Steven Frank Sheene MBE (11 September 1950 – 10 March 2003) was a British professional motorcycle racer and television sports presenter. He competed in Grand Prix motorcycle racing between 1971 and 1984, most prominently as a member of the Suzuki factory racing team where he won two consecutive FIM World Championships in 1976 and 1977.[1] Sheene remains the last British competitor to win the premier class of FIM road racing competitions.[2]

Good looking, articulate and charismatic, Sheene was able to harness the power of mass media to transcend the sport and become the best-known face of British motorcycle racing during the 1970s.[3] He was the first motorcycle racer to gain commercial endorsements from outside the sport, including television advertisements for Brut cologne.[3][4] As well as being fluent in several languages, he had a cheeky, cockney persona that endeared him to thousands of race fans.[3]

Sheene was also a strong proponent of race track safety, and was one of the first competitors to object to racing at the notoriously dangerous Isle of Man TT street circuit.[4][5] He recognized his value to race promoters as a gate attraction and used his influence to force race promoters to increase rider safety.[3][5]

After a racing career stretching from 1968 to 1984 he retired from competition and relocated to Australia, working as a motorsport commentator and property developer.[3][5] In 2011, the FIM inducted Sheene into the MotoGP Hall of Fame.[6]

Early life

[edit]Barry Steven Frank Sheene was born on September 11, 1950, off the Gray's Inn Road, Bloomsbury, London, where his father, Frank Sheene, worked as the resident engineer at the Royal College of Surgeons.[7][8][9][10][11] His father was a former competitive motorcyclist and an experienced motorcycle mechanic.[7][9][8] He grew up in Queen Square, Holborn, London, where he learned to ride a motorcycle at the age of 5 aboard a homemade minibike built by his father.[11] Before he raced motorcycles competitively, Sheene found work as a motorcycle courier and delivery driver.[3][5]

Career

[edit]First foray into racing

[edit]Sheene's father had developed a close, personal relationship with Don Paco Bultó, the owner of Bultaco motorcycles, after meeting him in 1959 while attending the Montjuïc 24 Hour endurance race in Barcelona.[12] Frank Sheene was one of the first proponents of the two-stroke engine that began to dominate the smaller engine classes of motorcycle racing in the mid-1960s.[12] Bultó began to supply the Sheene family with his latest motorcycles.[12]

As a young boy, Sheene first interest in competitive motorcycling was in off-road motorcycle trials however, he soon found that he enjoyed speeding between trials sections rather than the trial itself, and decided that he would be better at road circuits.[13] Sheene had no plans to become a motorcycle racer, instead he focused on learning the art of tuning two-stroke engines, which were difficult to master unless a person was prepared to dedicate considerable time in a workshop learning the intricacies of the engines.[11][12] However his father noticed that he was a naturally talented rider and he was entered into his first road race in 1968 at the age of 17 riding a Bultaco motorcycle.[11]

In his first race at the Brands Hatch Circuit, he suffered a crash when the engine on his 125cc Bultaco seized (The cc initials refer to the engine displacement in cubic centimeters).[11] Undaunted by the experience, he mounted his 250cc Bultaco a few minutes later and finished in third place in the 250 class.[11] Returning to Brands Hatch the following weekend, he would score his first victory.[7] Sheene then stopped racing to become the race mechanic for British privateer Lewis Young, who had entered his Bultacos in several European Grands Prix races.[12] His experiences from attending the European races seemed to ignite Sheene's interest in becoming a motorcycle racer.[12][13]

Sheene was not a keen school student and had an aversion to authority figures, so he began to see motorcycle racing as a possible career path.[3][11] He sometimes would skip school and attend practice sessions at nearby Brands Hatch circuit.[14] In 1969, Sheene began wearing a crash helmet with an image of Donald Duck on the front of his helmet to stand out from the crowd.[11] The helmet design would remain his trademark throughout his racing career, as well as his racing number 7.[11] He drilled a hole in the chin piece of his crash helmet so he could smoke a cigarette while waiting on the starting grid for a race to begin.[3][11] A cigarette smoker since the age of nine, he favoured Gitanes cigarettes with a heavy tar content, which would later contribute to his death from cancer in 2003.[15]

Sheene made a big impression as an eighteen-year-old in 1969 when he rode a Bultaco to place second behind Chas Mortimer in the 1969 125cc British Championship, and then dominated the 1970 125cc British Championship.[12] He also placed third in the 1970 250cc Championship aboard a Bultaco.[11] His father Frank served as his mechanic, a position he would hold throughout Sheene's racing career.

In 1970, Sheene and his father borrowed £2,000 (£36,720 in 2023), to purchase a twin-cylinder 125cc Suzuki RT67, a former factory racing team motorcycle campaigned by Stuart Graham in the 1968 World Championships and in selected 1969 events.[3][16] Although it was an expensive purchase, the ex-factory race bike helped to launch Sheene's international racing career.[11]

Sheene first met two-time American champion, Gary Nixon, in 1971 when Nixon was a member of the American team competing in that year's Transatlantic Trophy match races.[17] The Transatlantic Trophy match races pitted the best British riders against the top American road racers on 750cc motorcycles in a six-race series during Easter weekend in England. The two racers bonded and developed a lifelong friendship.[18] Sheene began wearing his Gary Nixon t-shirt beneath his leather riding suit as a good luck charm every time he raced.[11][19][20]

Grand Prix racing

[edit]In 1971 Sheene entered the 125cc World Championship aboard the same Suzuki.[3] He provoked a controversy at the 1971 Isle of Man TT races when he crashed out of the event while lying in second place, and then outraged traditionalists when he criticised the event as unworthy of Grand Prix status.[3] He loudly announced that it would be the last time he ever competed at the Isle of Man TT at a time when the race was considered the most prestigious event on the world championship calendar.[21][22][23] As a young boy, Sheene had attended the TT races with his father and appreciated the history of the event however, he felt that racing against the clock on a street circuit for world championship points was too dangerous.[3][4][24]

Sheene scored his maiden Grand Prix victory with a win at the 125cc Belgian Grand Prix held at the challenging Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps.[11] The championship battle in the 50cc World Championship between Derbi's Ángel Nieto and Kreidler's Jan de Vries was so heated, that the Kreidler team hired Sheene and Jarno Saarinen to race in support of de Vries, while the Derbi factory hired rider Gilberto Parlotti in support of Nieto.[21] After de Vries retired with engine problems, Sheene went on to win the 50cc Czechoslovakian Grand Prix held at the Masaryk Circuit, where he finished over two and a half minutes ahead of the competition.[1] By denying points to the opposition, Sheene helped de Vries secure the 1971 50cc World Championship.[1][25]

The 125cc championship then moved to the Scandinavian countries where Sheene won the Swedish and Finnish Grands Prix races to take the lead in the 125cc World Championship going into the final round at the Spanish Grand Prix held at the Jarama Circuit.[11] At the prestigious, non-championship Mallory Park Race of the Year, Sheene won the Lightweight Support Class ahead of Saarinen and Rod Gould, however he suffered a broken rib while competing in the Race of the Year.[26] The following weekend, while riding with the broken rib, he finished in third while his principle rival, Ángel Nieto won the race to clinch the 125cc World Championship. Nieto's victory relegated Sheene to second place in the World Championship, a respectable result considering it was his rookie season.[11][27] Sheene had immense respect for Nieto, calling him one of his greatest rivals.[21]

For the 1972 season, Sheene was signed by Yamaha factory to ride a specially made Yamaha YZ635 in the 250cc World Championship under the French Yamaha importer Sonauto's sponsorship. There was no Yamaha factory racing team at the time, but Sheene was one of six riders receiving support from the factory.[28] However, at the third round in Austria, after losing a sprint to the finish line to the Australian John Dodds for third place, he voiced his displeasure to team management about the performance of the motorcycle. The next Grand Prix was the Grand Prix of Nations at Imola at the end of May, but Sheene crashed in practice and broke his collarbone, preventing him from taking part in the race, and in the subsequent Isle of Man TT race as well.[29] The next seven races of the world championship all took place in close succession in June and July and Sheene was not fit to take part in them.

After the Yugoslavian Grand Prix, Sheene's factory-supported Yamaha YZ635 was given to Jarno Saarinen, already a Yamaha factory rider in the 350cc class, who went on to win four races and the 250cc World Championship that year.[30] Once back to fitness, Sheene would get factory-supported Yamahas back for British races over the summer (Silverstone, Scarborough, Mallory Park) and for the last Grand Prix of the season, at the Montjuïc circuit in Spain on 23 September, where he scored a third place in the 250cc class.[1]

1973 Suzuki team leader

[edit]Sheene was signed by the Suzuki factory racing team along with teammates Jack Findlay and Paul Smart during the off season 1972–1973. He began the 1973 season as a member of the British team riding a Suzuki TR750 in the 1973 Transatlantic Trophy match races where his best result came at the third round at Oulton Park, placing third behind Peter Williams on a John Player Norton and Yvon Duhamel on a Kawasaki H2R.[17]

Sheene then contested the British 500cc Championships riding a Suzuki TR500, but when he found that the motorcycle handled poorly, he replaced Suzuki's chassis with a frame designed by British constructor Colin Seeley.[3][24] He also rode the TR750 to contest the British 750cc Championship and won the newly formed Formula 750 European championship in 1973.[31][32] He was the first as well as the only non-Yamaha rider to win a Formula 750 championship.[32] As a Suzuki factory rider Sheene had two contracts, with the World Championship events taking precedence over his Suzuki GB contract for home and international events, if any race dates clashed.[33] At the end of the year, Sheene was voted "Man of the Year" by the readers of Motor Cycle News.[11]

Prior to the beginning of the 1974 season, the dominant MV Agusta factory racing team offered Sheene a position on their team, however Sheene refused their offer, knowing that Suzuki was developing a new motorcycle to compete in the 500cc class.[11] At the time, the 500cc class was considered to be the premier division in Motorcycle Grand Prix racing. It was not an easy decision for Sheene as the powerful MV Agusta team had won the previous 16 500cc World Championships.

Sheene was again named to the British team for the 1974 Transatlantic Trophy match races where he first encountered American racer, Kenny Roberts, who would become his arch-rival. Roberts twice relegated Sheene to second place in two heat races at Mallory Park before Sheene was able to win over Roberts in the first race at Oulton Park.[17] Roberts then reversed the results in the final event of the series.[17] Sheene's TR750 motorcycle was no match for Robert's water-cooled Yamaha TZ750 which, would dominate the 750cc class throughout the 1970s.[34]

1974: Development of the RG500

[edit]

Suzuki introduced the new RG500 motorcycle for the 1974 season and Sheene secured its first podium results when he rode the raw, unrefined machine to a second place in France and a third place in Austria to start the season. However, Sheene suffered a broken leg in a crash at the Nations Grand Prix held at the Imola Circuit forcing him to miss the next six rounds of the World Championship.[35][36] Upon recovering from his injury, he placed fourth at the Czechoslovakian Grand Prix, and finished the season ranked sixth in the 1974 500cc World Championship.[1] Also in 1974, he won the prestigious Mallory Park Race of the Year.[37]

At the end of the 1974 season, the Suzuki factory was left disappointed by their efforts on the RG500 project and seemed to be losing their motivation to continue.[38] However, Sheene had become vested in the project and took pride in seeing his suggested modifications being implemented and improving the motorcycle's performance.[38] He urged the factory to continue their efforts, offering to stay in Japan to help them develop the motorcycle until it performed to his satisfaction.[38] Suzuki agreed and he spent five weeks in Japan during the offseason, helping engineers on the development work for the RG500.[38]

Daytona crash

[edit]By the mid-1970s the Daytona 200 motorcycle race had become one of the most important motorcycle races for manufacturers, as they fought for shares of the burgeoning American motorcycle market fueled by the baby boomer generation.[39] The 1974 victory by 15-time world champion Giacomo Agostini helped cement the Daytona 200's reputation as one of the most prestigious motorcycle races in the world.[39]

Sheene arrived for the 1975 Daytona 200 with a BBC documentary team following him to record his experiences.[20][40] The BBC crew was filming Sheene during practice for the race when the tyre on Sheene's motorcycle delaminated at approximately 180 mph.[40] The motorcycle pitched sideways, sending Sheene tumbling down the track. He suffered severe injuries including; a broken left femur, right arm, collarbone and two ribs. The BBC coverage of his accident and subsequent recovery made Sheene a household name in Britain.[3][4][24]

The Jet-Set lifestyle

[edit]As Sheene's racing career flourished, so did his fame and fortune. He enjoyed a lavish lifestyle, driving a Rolls-Royce and buying a helicopter which he learned to fly.[20][41] He was often seen in the company of fashion models and musicians and was personal friends with James Hunt, Ringo Starr and George Harrison.[10][41][42]

In 1975 while on crutches from his Daytona accident, Sheene met fashion-model-turned-glamour-model Stephanie McLean, who was Penthouse Pet of the Month for April 1970 and Pet of the Year in 1971, while they were working together on a photoshoot for Chrysler. He made tabloid news in Britain when McLean left her first husband for Sheene.[5] They would marry in 1984 and had two children, Sidonie and Freddie.[11][41][43]

He became the motorcycling racing's first multi-millionaire, purchasing homes in Putney, in south-west London, and in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, and in 1977 he purchased a 700-year-old manor house in Charlwood, Surrey once owned by the actress Gladys Cooper.[10] A shrewd businessman with a penchant for self-promotion, he attracted sponsors from outside the motorcycle industry from clothing, electronics and tobacco companies.[10] He was also contracted by Faberge to promote their Brut aftershave lotion alongside boxer Henry Cooper.[5]

1975: Return to form

[edit]Despite his serious injuries, Sheene recovered and was racing again seven weeks afterwards. On June 28, only three months after his horrific crash at Daytona, he returned to the world championship at the Assen TT Circuit for the 1975 Dutch TT. Sheene surprised observers who may have expected a gradual return to health by claiming the pole position over second-placed, Giacomo Agostini, now riding for the Yamaha factory racing team. Agostini was nearing the end of his career while the twenty-five-year-old Sheene was approaching his prime.[44] Sheene then claimed a dramatic victory in the race with a well-planned, last corner pass around the outside of Agostini. Both competitors received the same race time.[7][44][45]

At the 1975 Swedish Grand Prix, Sheene set the lap record while winning the Formula 750 round on Saturday, then set the 500cc lap record while winning the 500cc Grand Prix race on Sunday.[46] He started the 500cc race slowly, but worked his way through the field to catch and pass both Agostini and Phil Read, who were the championship points leaders.[46] Sheene took the victory ahead of Read while Agostini crashed out of the race.[46] He placed sixth in the 1975 500cc World Championship, but his late season victory showed that Suzuki was becoming a serious challenger.[1] Sheene won three rounds of the 1975 Formula 750 championship, but finished one point behind the eventual champion, Jack Findlay aboard a Yamaha TZ750, who was able to score consistently in six rounds.[47] Sheene once again won the Mallory Park Race of the Year.[37]

Sheene returned to Daytona in 1976, where he flamboyantly drove around the town in a Rolls-Royce on loan to him from the local dealer.[48] However, by 1976 the 750cc class was becoming dominated by the powerful Yamaha TZ750.[34] Agostini's 1974 Daytona 200 victory on a Yamaha TZ750 marked the first of ten consecutive Daytona victories for the TZ750.[34] Sheene circulated as high as third place on his under-powered Suzuki until he was forced to retire with engine problems.[20][49]

Back in Europe, Sheene was the top British points scorer and the only British rider to score a win with a victory at Mallory Park, as Great Britain defeated the United States in the 1976 Transatlantic Trophy match races. However, Yamaha's Steve Baker was the dominant rider with four victories in the six race series.[50][51]

1976 World Champion

[edit]In the 500cc World Championships, Sheene worked hard to develop the RG500 race bike with his Suzuki team engineers, and by the 1976 season, his Suzuki was at the cutting edge of motorcycle racing technology.[3][11] However, Yamaha had withdrawn their factory team from the World Championships and the Suzuki factory wanted to do the same in order to concentrate their funding on development of the company's first range of four-stroke production motorcycles known as the Suzuki GS series.[52] The factory also began to produce customer versions of the RG500 and made them available to the public in 1976.

Suzuki's British importer intervened and convinced the Suzuki factory to allow the importer to continue as Suzuki's representative in the World Championships. Riders John Newbold and John Williams joined Sheene on the British Suzuki team that became known as the Heron-Suzuki team after their principle sponsor, Heron International.[42] Without Japanese mechanics to support him, Sheene put together a team consisting of his father Frank and Don Mackay, an electrician by trade.[52][42] The customer version of the RG500 was immediately competitive and became the motorcycle of choice for privateer racers including; Phil Read, Teuvo Länsivuori and newcomers Marco Lucchinelli and Pat Hennen.[3]

With Sheene fully recovered from his Daytona injuries, he took control of the championship from the start of the season by winning the first three races, including a dramatic race-long battle with Read at the Nations Grand Prix where Sheene won by 0.1 seconds.[1][53] After sitting out the 1976 Isle of Man TT (then in its final season on the World Championship calendar), he won the Dutch TT by 45 seconds over Hennen before his motorcycle experienced mechanical trouble at the Belgian Grand Prix and he placed second to his Suzuki GB teammate John Williams.[1]

The loss of Japanese technical support became apparent at a British championship race at the Snetterton Circuit when someone had forgotten to insert his motorcycle's brake pins, causing Sheene to crash when the brakes failed.[52] The damage required a complete rebuild of the motorcycle, and when they arrived at the next World Championship round in Sweden, they discovered that the wrong triple clamps were installed on his number one motorcycle, while the wrong gearbox had been installed in his number two motorcycle.[52] Sheene then discovered that one brake pad had been inserted backwards, a potentially fatal error. Although suspicion fell on his elderly father, who was his lead mechanic, Sheene never publicly blamed anyone for mistakes.[52] The team recovered from their self-inflicted errors with Sheene qualifying second-fastest in Sweden behind pole-sitter Länsivuori.[52]

Sheene experienced more drama during qualifying for the Swedish Grand Prix when his teammate, John Williams was knocked unconscious after a hard crash. Sheene stopped his motorcycle on the racetrack and rushed to Williams' aide, removing his teammate's helmet and clearing his airway after he had swallowed his tongue, thus preventing further injury.[54]

Sheene then clinched the World Championship by winning the Swedish Grand Prix with three races left in the championship.[1] He claimed the title with an impressive 136 points, 81 points more than second-placed Länsivuori.[1] Sheene was the first 500cc champion from the Japanese marque, and remains the only person to win more than one World Championship on a Suzuki motorcycle. Without any major factory teams in the championship, the customer version of the RG500 dominated the standings.

Sheene liked to win races off the track as well as on the track, often using psychological games to distract or upset his rivals.[18] He used his status with the Suzuki factory to ensure that he received the best RG500 engines over his teammates.[18] Sheene's elevated status within the team eventually led to the departure of John Williams after the 1976 season, feeling that Sheene was receiving preferential treatment.[18]

1977: Repeat champion

[edit]Williams was replaced on the Suzuki team by rising talent, 23-year-old Pat Hennen, the first American rider to win a 500cc Grand Prix. Recognizing the threat that Hennen posed to his position at the top of the team's hierarchy, Sheene would employ the same psychological tactics on Hennen that he had used on Williams, publicly disparaging his new American teammate by telling journalists, “If you pay peanuts, you get a monkey.”[18][55] Hennen was joined on the Suzuki team by Steve Parrish, who rode Sheene's 1976 Suzuki 500cc machine.[56]

Sheene was once again the top British points scorer at the 1977 Transatlantic Match races, however Suzuki lacked a 750cc motorcycle to compete with the dominant Yamaha TZ750 and Roberts won the first four races of the series before his motorcycle failed during the first race at Oulton Park allowing Sheene to claim the victory.[57] The top American points scorer at the Match races was Sheene's Suzuki teammate, Hennen, serving notice that he would be a contender in the coming 500cc World Championship.[57]

Sheene was even more dominant in the 1977 facing off against a revived Yamaha factory effort supporting Giacomo Agostini, Johnny Cecotto and Steve Baker. He claimed the World Championship with six Grand Prix victories, finishing well clear of second placed Baker.[1] His victory in the 1977 Belgian Grand Prix marked the fastest Grand Prix in history with an average race speed of 135.067 mph (217.369 kph).[58] The following year, the Spa-Francorchamps road course was replaced by a shorter, safer track, meaning that Sheene's record could never be broken.[58]

Sheene's campaign for increased rider safety was galvanized at the second round of the 1977 season held at the Salzburgring circuit, when a significant accident during the 350cc race killed Hans Stadelmann and left Johnny Cecotto, Dieter Braun and Patrick Fernandez with serious injuries.[58] The lack of onsite medical facilities exasperated situation and exposed the race organizers' callousness and indifference regarding the safety of competitors.[58] Sheene and most other 500 class riders refused to race, despite the race organizers offering riders double the usual start money.[58] For his efforts, the FIM race jury issued official warnings to Sheene and other riders.[58]

Although Sheene sought a psychological advantage over his rivals, he could also be generous as he was with Steve Baker who had been released by Yamaha after placing second to Sheene in the 1977 500cc World Championship. Baker was determined to stay and compete in Europe, and with the help of Sheene, he was able to secure a motorcycle and sponsorship from the Suzuki of Italy racing team operated by former Grand Prix competitor, Roberto Gallina.[18]

1978: The American wave

[edit]A sense of excitement had built up at the beginning of the 1978.[21] The popularity of motorcycle racing had waned after years of stagnation under the domination of the MV Agusta factory racing team led by multi-time world champion, Agostini, however, the Japanese manufacturers were showing a renewed vigor to compete.[59] Sheene's popularity had injected some much-needed interest back into the sport along with the arrival of American champion Kenny Roberts.[59] Sheene's influence and the arriving American riders boosted attendance at the tracks and spurred the growth in television coverage.[59]

Roberts considered himself primarily a dirt track racer and only participated in American road racing events because they were on the AMA Grand National Championship schedule. He had only transferred to competing in the World Championships because Yamaha lacked a competitive dirt track motorcycle to challenge the dominant Harley-Davidson dirt track team.[60] Roberts said that he was initially indifferent about competing in Europe however, after reading a guest column written by Sheene in the Motor-Cycle News, in which he dismissed Roberts as being, "No threat", citing the Yamaha rider's lack of familiarity with most of the European race circuits, the American rider made up his mind to compete.[60] Sheene and Roberts had a fierce rivalry on and off the track, but they also respected each other as competitors.[61][62]

Roberts brought a new style of riding, forged on the dirt track ovals of America that would revolutionize road racing.[21][63] His riding style was reminiscent of dirt track riding, where sliding the rear tire to one side is used as a method to steer the motorcycle around a corner.[21] Sheene was the last exponent of the smooth, European riding style which emphasized maintaining as much corner speed as possible without sliding the rear tire.[21] After Roberts, the world championships became dominated by a string of American and Australian riders bred on dirt track racing.[42][64]

At the pre-season 1978 Transatlantic Trophy match races, Sheene won the first of two races at Brands Hatch, but in the second race, Hennen was able to pass Sheene on the inside of the final corner to win the race.[10] Sheene was angered by what he perceived as a dangerous pass and publicly berated his Suzuki teammate.[10] Hennen was the top points scorer at the 1978 Transatlantic Match races, winning three races as well as two second places and one third place.[65] Later in the week, Sheene continued the psychological warfare on his teammate when he repeated the accusation of dangerous riding in his guest column in Motor-Cycle News.[10]

Suzuki produced a new version of the RG500 with a shortened frame for the1978, and although Sheene began the year on a positive note with a victory at the 1978 Venezuelan Grand Prix, the new version proved to be a setback for the RG500's development.[4] Hennen won the Spanish Grand Prix then Roberts won three races in succession.[1] After the first five races, Sheene trailed Roberts by eight points and his Suzuki teammate, Hennen, by five points.[55] During a mid-season break in the Grand Prix schedule, Hennen suffered career-ending injuries while competing in the 1978 Isle of Man TT races.[55]

The Suzuki factory contracted Dutch rider Wil Hartog to replace Hennen on the team, ostensibly to help Sheene fend off the Yamahas of Roberts and Cecotto, however Sheene was unhappy when his new teammate won the 1978 Belgian Grand Prix ahead of Roberts and Sheene in second and third places.[66] Hartog had made the correct tire choice for the deteriorating weather conditions and was able to win by a 16-second margin.[66] Sheene fought back with a string of podium finishes and with a victory at the Swedish Grand Prix, he had cut Roberts' points lead to three points with three rounds left in the championship.[1]

It was at this crucial point in the championship that Sheene's relationship with Suzuki began to sour.[21] At the Finnish Grand Prix, Sheene had an opportunity to overtake Roberts in the points lead when the Yamaha rider failed to finish the race due to a mechanical failure, however Sheene's Suzuki also failed allowing his teammate Hartog to win his second race of the year.[1] During a pre-race practice session, Sheene's well-trained ear thought he heard a failing crankshaft bearing in his engine.[21] He requested that it be replaced, but his Suzuki mechanics disagreed with his assessment and refused his request.[21] When the crankshaft failed during the race, the outspoken Sheene publicly criticised his team's decision.[21]

The 1978 British Grand Prix ended in controversy when torrential rains during the race, along with pit stops for tire changes by both Roberts and Sheene, created confusion among official scorers.[22][67] Sheene took to the public address system during the confusion to declare that he had won the race however, an FIM Jury eventually declared that Roberts was the winner with Sheene being awarded third place behind privateer Steve Manship, who did not stop for a tire change.[68][69] At the final round in Germany, Roberts finished third ahead of Sheene in fourth place to claim the 500cc title, dropping Sheene to second place in the world rankings.[1] Sheene blamed the loss of the 1978 World Championship on his team's sluggish response to his request in Finland.[21] He won his third Mallory Park Race of the Year in 1978.[37]

1979: Final year with Heron-Suzuki

[edit]Sheene's relationship with Suzuki was further soured before the 1979 season when, the Suzuki factory asked its three top riders, Sheene, Virginio Ferrari and Wil Hartog to choose the new factory race bike by comparing two versions.[70] Sheene, used to receiving preferential treatment from Suzuki, was outvoted when Ferrari and Hartog chose the motorcycle that he had rejected and, he was forced to ride their choice rather than his preferred choice.[70]

The 1979 Transatlantic Trophy match races saw Sheene claim the first four races of the series against a depleted American team that was missing Roberts and Hennen due to injuries.[71] Sheene's motorcycle suffered engine problems at Oulton Park allowing Gene Romero to win the final two races of the series.[71]

Sheene began the 1979 season with a victory over teammate Ferrari at the Venezuelan Grand Prix, while Roberts was recovering from career-threatening back injuries suffered during a pre-season testing crash in Japan.[21] Roberts returned to win the second round in Austria despite still recovering from his injuries, while Sheene suffered from a mechanic's mistake when installing his brake pads, causing him to finish in 12th place.[21] He then failed to finish in three of the next four races as Roberts won three consecutive races in Italy, Spain and Yugoslavia to take the championship points lead.[1] Sheene placed second to Ferrari at the Dutch TT before all the factory teams boycotted the Belgian Grand Prix due to the dangerous track conditions.[1] He then won the Swedish Grand Prix followed by a third place in Finland.[1]

Sheene's battle with Kenny Roberts at the 1979 British Grand Prix at Silverstone has been cited as one of the greatest motorcycle Grand Prix races of the 1970s.[72][73][74] The race began with Roberts, Sheene and Wil Hartog breaking away from the rest of the field of riders. Hartog eventually fell behind as Roberts and Sheene continued to battle for the lead.[72] The event featured numerous lead changes throughout the 28 lap race.[72] Heading into the final lap of the race, the two leaders came upon lapped riders. Roberts was unhindered as he passed the slower riders however, Sheene was momentarily held up, allowing Roberts to increase his lead.[72] An undeterred Sheene put in an impressive lap time to catch Roberts as they entered the final corner.[72] With momentum on his side, Sheene attempted a last second pass, but Roberts was able to prevail over Sheene by a narrow margin of just three-tenths of a second.[72] The hard-fought race, which was broadcast live by the BBC, cemented the fierce rivalry between the two competitors in the annals of motorcycle Grand Prix racing history.[61][72][74] Years later, when informed of Sheene's death from cancer in 2003, Roberts simply stated, "I wouldn't be Kenny Roberts without Barry Sheene".[61][62]

Sheene recovered to win the final race of the season at the French Grand Prix, but Roberts placed third to secure his second consecutive 500cc World Championship.[1] Despite winning more races than any other Suzuki rider in 1979, Sheene finished the season in third place, two points behind Ferrari on the Gallina-Suzuki.[1]

Riders revolt

[edit]During the 1979 season, the riders boycott of the 1979 Belgian Grand Prix highlighted the increasing animosity between motorcycle racers and the FIM concerning rider safety. The Belgian circuit had been paved just days before the race, creating a track that many of the racers felt was unsafe due to diesel fuel seeping to the surface.[75] Roberts began talking to journalists about forming a rival racing series to compete against the FIM's monopoly.[21] At the end of the 1979 season, Sheene joined Roberts and British motorsports journalist, Barry Coleman, in announcing their intention to break away from the FIM and create a rival race series called the World Series, with most of the top Grand Prix racers joining the revolt.[76][77]

The death of Gilberto Parlotti at the 1972 Isle of Man TT along with the deaths of Jarno Saarinen and Renzo Pasolini in 1973 highlighted the need for improved safety standards for motorcycle racers.[78] At the time, many motorcycle Grand Prix races were still being held on street circuits with hazards such as telephone poles and railroad crossings.[21] Dedicated race tracks of the time were also dangerous for motorcycle racers due to the steel Armco trackside barriers preferred by car racers.[78] Tensions over safety issues continued to simmer throughout the 1970s between the Grand Prix racers, race organizers and the FIM, as riders showed their increasing dissatisfaction with the safety standards and the way races were organized by boycotting several Grand Prix races.[21][79]

Although the competing series was not successful due to difficulties in securing enough venues, it forced the FIM to take the riders' demands seriously and make changes regarding their safety.[21][59] During the 1979 FIM Congress, new rules were passed substantially increasing prize money and in subsequent years, stricter safety regulations were imposed on race organizers.[21]

Move to Yamaha

[edit]

Believing that he was receiving inferior equipment to his Suzuki teammates, Sheene made the decision to switch manufacturers for the 1980 season. He campaigned on a privateer Yamaha YZR500, but Yamaha remembered his outspoken criticism of their motorcycle in 1972 and withheld their best machinery for Kenny Roberts who captured his third consecutive 500cc World Championship in 1980.[14]

With the help of the British Yamaha importer, Mitsui-Yamaha, Sheene began receiving more favorable treatment from the Yamaha factory.[24] In 1981, Sheene retained the services of the recently retired Gary Nixon's former mechanic, Erv Kanemoto, who helped Sheene score two podium results before winning the final round of the series at the Anderstorp Raceway in Sweden, taking fourth overall in the 1981 500cc World Championship.[1][24] Gallina-Suzuki's Marco Lucchinelli took command of the season with four victories in five races to claim the world championship ahead of Sheene's replacement on the Heron-Suzuki team, Randy Mamola. Sheene's victory at the 1981 Swedish Grand Prix would be the last Grand Prix victory by a British competitor for 35 years, until Cal Crutchlow ended the streak by winning the 2016 Czech Republic Grand Prix.[24]

If Barry had stayed with Suzuki, he would definitely have won more championships.

Sheene received the latest Yamaha OW60 TZ500 motorcycle before the 1982 season, on par with Roberts machinery and showed he was back on form by claiming five out of six races at the 1982 Transatlantic Trophy match races, although the American team had been depleted by the absence of Roberts and Randy Mamola due to testing commitments.[80] Then American newcomer, Freddie Spencer crashed and damaged his Honda so badly in the first race, that he had to abandon the remainder of the series.[80] Only a low-speed crash on the last lap at the Mallory Park hairpin turn allowed Roger Marshall to pass and deprive Sheene of a $40,0000 bonus for being the first competitor to win all six races in one year.[80]

Silverstone accident

[edit]With Yamaha's top machinery for the 1982 season, Sheene was immediately competitive, finishing just 0.670 seconds behind Roberts at the Argentine Grand Prix followed by a second place behind Franco Uncini on the Gallina-Suzuki RG500 at the Austrian Grand Prix. After the top riders boycotted the French Grand Prix, he produced a string of podium positions and was in contention for the world championship once again, when he suffered the second serious accident of his career during practice for the 1982 British Grand Prix.[3][11] During unofficial practice on Thursday at the Silverstone Circuit, Sheene came over a blind rise and collided with Patrick Igoa's motorcycle at over 160 mph, shattering both legs and breaking an arm.[7][41]

His injured legs were saved by orthopaedic surgeon Mr Nigel John Cobb FRCS at the nearby Northampton General Hospital.[81] Although he would return to the world championships in 1983 racing a privateer Suzuki RG500, he never regained his old form and he retired in 1984.[3][11] Fittingly for a rider whose name had become synonymous with the Suzuki RG500, after having scored the motorcycle's first podium position in 1974, he was also the rider who secured its final podium with a third-place result at the 1984 South African motorcycle Grand Prix.[36] He remains the only rider to win Grand Prix races in the 50 cc and 500 cc categories.[82]

The final major victory of Sheene's motorcycle racing career came at the 1984 Scarborough Gold Cup held at the Oliver's Mount circuit, one of his favorite venues.[24] He took the victory over his old foe, Mick Grant marking the fourth time he had won the Scarborough Gold Cup race.[24]

Television career

[edit]Sheene worked as a Television presenter, including the ITV series Just Amazing!, where he interviewed people who had, through accident or design, achieved feats of daring and survival (including the former RAF air gunner, Nicholas Alkemade, who survived a fall of 18,000 feet without a parachute from a blazing Avro Lancaster bomber over Germany in March 1944). He was the subject of This Is Your Life in 1978 when he was surprised by Eamonn Andrews at a motor racing cycle exhibition in London's Victoria. Sheene and his wife, Stephanie McLean, also starred in the low-budget film Space Riders.[11]

Later life and death in Australia

[edit]The Sheene family moved to Australia in the late 1980s, in the hope that the warmer climate would help relieve some of the pain of Sheene's injury-induced arthritis, settling in a property near the Gold Coast.[11] He combined a property development business with a role as a commentator on motor sport. He began on SBS TV then moved to the Nine Network with Darrell Eastlake, and finally followed the TV broadcast rights of the Grand Prix motorcycle series to Network Ten.[3][11] Further to this, on Network Ten Sheene co-hosted the weekly motor sport television show RPM from 1997 to 2002 with journalists Bill Woods and Greg Rust and was involved in Ten's coverage of other motor sport including V8 Supercars for several years. In the 1990s, Sheene appeared in a series of well-known and popular television advertisements for Shell, with Australian motor sport icon Dick Johnson.

With his personal connections in the motorcycle industry, Sheene helped boost the racing careers of young Australian motorcycle racers such as five-time 500cc World Champion, Mick Doohan, two-time Superbike World Champion, Troy Corser and MotoGP Grand Prix winner, Chris Vermeulen.[61][83][84] In later years, Sheene became involved in historic motorcycle racing,[5] often returning to England to race at Donington Park. Sheene competed in his last race in Britain at the Goodwood Revival in 2002. He was also chosen to run with the Queen's Baton in the run-up to the 2002 Commonwealth Games held in Manchester, England.

In July 2002, at the age of 51, Sheene was diagnosed with cancer of the oesophagus and stomach.[41] Refusing conventional treatments involving chemotherapy, Sheene instead opted for a holistic approach involving a strict diet devised by Austrian healer Rudolf Breuss, intended to starve the cancer of nourishment.[5][41]

He died at a hospital on Queensland's Gold Coast in March 2003, aged 52, having suffered from the condition for eight months.[41]

Honours and awards

[edit]In 1978, Sheene was appointed MBE for services to motorcycle sport.[11] He was a two-time Segrave Trophy recipient in 1977 and 1984 for his career in motorcycle Grand Prix racing.[85] Following reconstruction of the Brands Hatch Circuit in England for safety concerns after requests by the FIM, the Dingle Dell section was changed for safety, and shortly after Sheene's death the new section was renamed Sheene's Corner in his honour.[86] The FIM named him a Grand Prix "Legend" in 2001.[6] For the 2003 season, V8 Supercars introduced a medal in honour of Sheene, the Barry Sheene Medal, for the 'best and fairest' driver of the season. A memorial ride from Bairnsdale to Phillip Island, Victoria is held by Australian motorcyclists annually, before the MotoGP held at the island.[87]

In popular culture

[edit]A song titled "Mr. Sheene" that describes "Mr. Sheene's riding machine" was recorded by comedians Eric Idle and Rikki Fataar and released in 1978 as the B-side of the single "Ging Gang Goolie" under the names Dirk and Stig, their characters in Beatles-parody band The Rutles.[9]

In the UK television series Queer as Folk, the main characters Stuart and Vince reminisce about their teenage attraction to a photo of Sheene "On his motorbike! In his leathers..."[88]

In a Sleaford Mods song Dirty Den the character is mentioned "falling off the wagon like Barry Sheen".

Career statistics

[edit]The following is a list of results achieved by Sheene.

Motorcycle Grand Prix results

[edit]| Position | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Points | 15 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

(key) (Races in bold indicate pole position; races in italics indicate fastest lap)

| Year | Class | Team | Machine | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | Points | Rank | Wins |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 125cc | Sheene | Suzuki RT67 | GER - |

FRA - |

YUG - |

IOM - |

NED - |

BEL - |

DDR - |

CZE - |

FIN - |

ULS - |

NAT - |

ESP 2 |

12 | 13th | 0 | |

| 1971 | 50cc | Kreidler | Kreidler 50 | AUT - |

GER - |

NED - |

BEL - |

DDR - |

CZE 1 |

SWE 4 |

NAT - |

ESP - |

23 | 6th | 1 | ||||

| 125cc | Sheene | Suzuki RT67 | AUT 3 |

GER - |

IOM DNF |

NED 2 |

BEL 1 |

DDR 2 |

CZE 3 |

SWE 1 |

FIN 1 |

NAT 3 |

ESP 3 |

79 | 2nd | 3 | |||

| 250cc | Derbi | Derbi 250 | AUT - |

GER - |

IOM - |

NED - |

BEL - |

DDR 6 |

CZE - |

SWE - |

FIN - |

ULS - |

NAT - |

ESP - |

5 | 33rd | 0 | ||

| 1972 | 250cc | Sheene | Yamaha TD-3 (YZ635) | GER - |

FRA - |

AUT 4 |

NAT - |

IOM - |

YUG - |

NED - |

BEL - |

DDR - |

CZE - |

SWE - |

FIN - |

ESP 3 |

18 | 13th | 0 |

| 1973 | Formula 750 | Suzuki | TR750 | ITA - |

FRA 1 |

SWE 3 |

FIN 2 |

GBR DSQ |

GER 2 |

ESP 2 |

61 | 1st | 1 | ||||||

| 1974 | 500cc | Suzuki | RG500 | FRA 2 |

GER - |

AUT 3 |

NAT - |

IOM - |

NED - |

BEL - |

SWE - |

FIN - |

CZE 4 |

30 | 6th | 0 | |||

| 1975 | 500cc | Suzuki | RG500 | FRA - |

AUT - |

GER - |

NAT - |

IOM - |

NED 1 |

BEL DNF |

SWE 1 |

FIN - |

CZE DNF |

30 | 6th | 2 | |||

| Formula 750 | Suzuki | TR750 | USA - |

ITA - |

BEL - |

FRA 1 |

SWE 1 |

FIN - |

UK 1 |

NED - |

GER - |

45 | 2nd | 3 | |||||

| 1976 | 500cc | Heron-Suzuki | RG500 | FRA 1 |

AUT 1 |

NAT 1 |

IOM - |

NED 1 |

BEL 2 |

SWE 1 |

FIN - |

CZE - |

GER - |

72 | 1st | 5 | |||

| 1977 | 500cc | Heron-Suzuki | RG500 | VEN 1 |

AUT - |

GER 1 |

NAT 1 |

FRA 1 |

NED 2 |

BEL 1 |

SWE 1 |

FIN 6 |

CZE - |

GBR NC |

107 | 1st | 6 | ||

| 1978 | 500cc | Heron-Suzuki | RG500 | VEN 1 |

ESP 5 |

AUT 3 |

FRA 3 |

NAT 5 |

NED 3 |

BEL 3 |

SWE 1 |

FIN NC |

GBR 3 |

GER 4 |

100 | 2nd | 2 | ||

| 1979 | 500cc | Heron-Suzuki | RG500 | VEN 1 |

AUT 12 |

GER NC |

NAT 4 |

ESP NC |

YUG NC |

NED 2 |

BEL DNS |

SWE 1 |

FIN 3 |

GBR 2 |

FRA 1 |

87 | 3rd | 3 | |

| 1980 | 500cc | Akai-Yamaha | YZR500 (OW48) | NAT 7 |

ESP 5 |

FRA NC |

NED NC |

BEL - |

FIN - |

GBR NC |

GER - |

10 | 15th | 0 | |||||

| 1981 | 500cc | Akai-Yamaha | YZR500 (OW54) | AUT 4 |

GER 6 |

NAT 3 |

FRA 4 |

YUG 5 |

NED NC |

BEL 4 |

RSM 2 |

GBR NC |

FIN NC |

SWE 1 |

72 | 4th | 1 | ||

| 1982 | 500cc | JPS-Yamaha | YZR500 (OW60) | ARG 2 |

AUT 2 |

FRA - |

ESP 2 |

NAT - |

NED 3 |

BEL 2 |

YUG 3 |

GBR DNS |

SWE DNS |

RSM DNS |

GER DNS |

68 | 5th | 0 | |

| 1983 | 500cc | HB-Suzuki | RG500 | RSA 10 |

FRA 7 |

NAT 9 |

GER NC |

ESP - |

AUT 13 |

YUG 13 |

NED NC |

BEL - |

GBR 9 |

SWE NC |

RSM NC |

9 | 14th | 0 | |

| 1984 | 500cc | HB-Suzuki | RG500 | RSA 3 |

NAT NC |

ESP 7 |

AUT 10 |

GER 10 |

FRA 5 |

YUG 7 |

NED NC |

BEL 9 |

GBR 5 |

SWE NC |

RSM NC |

34 | 6th | 0 | |

| Sources:[1][23][31] | |||||||||||||||||||

Complete British Saloon Car Championship results

[edit](key) (Races in bold indicate pole position; races in italics indicate fastest lap.)

| Year | Team | Car | Class | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | DC | Pts | Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1981 | Mazda Motorsport / TWR | Mazda RX-7 | C | MAL Ret† |

SIL | OUL | THR | BRH | SIL | SIL | DON | BRH | THR | SIL | NC | 0 | NC | |

| 1985 | Team Toyota GB / Hughes of Beaconsfield | Toyota Celica Supra | A | SIL 5 |

OUL Ret |

THR 3 |

DON Ret |

THR DNS |

SIL 3 |

DON 5 |

SIL Ret |

SNE Ret |

BRH 4 |

BRH DNS |

SIL 6 |

16th | 18 | 6th |

| 1986 | Team Toyota GB / Duckhams | Toyota Corolla GT | C | SIL | THR | SIL | DON | BRH | SNE | BRH | DON | SIL 11 |

NC | 0 | NC | |||

Source:[89]

| ||||||||||||||||||

† Events with 2 races staged for the different classes.

Complete European Touring Car Championship results

[edit](key) (Races in bold indicate pole position) (Races in italics indicate fastest lap)

| Year | Team | Car | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | DC | Pts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | Volkswagen Golf GTI | MNZ | VAL | MUG | BRH | JAR | ZEL | BRN | NUR | ZAN | SAL | PER | SIL Ret |

ZOL | NC | 0 | ||

| 1985 | Toyota Celica Supra | MNZ | VAL | DON | AND | BRN | ZEL | SAL | NUR | SPA Ret |

SIL | NOG | ZOL | EST | JAR | NC | 0 | |

| 1986 | Mitsubishi Starion Turbo | MNZ | DON | HOC | MIS | AND | BRN | ZEL | NÜR | SPA | SIL Ret |

NOG | ZOL | JAR | EST | NC | 0 | |

Source:[90]

| ||||||||||||||||||

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v "Rider Statistics - Barry Sheene". MotoGP.com. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ^ "motogp.com · STATISTICS - wc-winners - All-seasons MotoGP All-countries". motogp.com. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "Barry Sheene". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Sheene: Cockney Rebel". motorsportmagazine.com. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Barry Sheene". The Telegraph. 11 March 2003.

- ^ a b "MotoGP Legends". motogp.com. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Barry Sheene - An Amazing Life". MCN.com. 4 March 2003.

- ^ a b Motorcyclist Illustrated, May 1968. p.35/37 "Joe Dunphy's Diary (all about Dave Croxford)" "Do you like two-strokes? I don't mind Frank Sheene's, they don't seize" Accessed 26 February 2014

- ^ a b c redbull.com "Remembering Barry Sheene". Retrieved 3 January 2014

- ^ a b c d e f g Clive Gammon (June 1978). "Making A Bloody Good Go Of It". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 12 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Mac McDiarmid (11 March 2003). "Barry Sheene obituary at The Independent". independent.co.uk. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The name Sheene meant nothing". motorsportmagazine.com. 21 April 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ a b Peck, Alan (1973). "Profile: Barry Sheene". Cycle World. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ a b Scott, Michael (1985). "Farewell to Barry Sheene: Britain's Ambassador to Racing". Cycle World. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ Frank Thorne (13 April 2013). "Barry Sheene dies of cancer". standard.co.uk. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ Barry: The Story of Motorcycling Legend, Barry Sheene - Steve Parrish, Nick Harris - Hachette UK, 2015 ISBN 0751560499, 9780751560497 - page 1850

- ^ a b c d "Transatlantic Trophy Match Races". Racingmemo.free.fr. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f DeWitt, Norm (16 September 2010). Grand Prix Motorcycle Racers: The American Heroes. MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 9781610600453.

- ^ Broadbent, Rick (2017), Barry Sheene: The Official Photographic Celebration of the Legendary Motorcycle Champion, Bloomsbury Publishing, ISBN 978-0747545118

- ^ a b c d Scalzo, Joe (1976). "High Flyin' Barry Sheene". Cycle World. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Dennis, Noyes; Scott, Michael (1999), Motocourse: 50 Years Of Moto Grand Prix, Hazleton Publishing Ltd, ISBN 1-874557-83-7

- ^ a b "Patriot Games: The British Grand Prix". visordown.com. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Barry Sheene Isle of Man TT results". iomtt.com. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Barry Sheene's 10 career defining moments". devittinsurance.com. 18 October 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ The Classic Motor Cycle July 1996, p.43 "25 Years Ago" Accessed and added 2014

- ^ "Mallory Park Celebrates 50th Anniversary Of The Race Of The Century". cartersport.com. 8 December 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ Barry: The Story of Motorcycling Legend, Barry Sheene - Steve Parrish, Nick Harris - Hachette UK, 2015 ISBN 0751560499, 9780751560497 - page 1853

- ^ ISBN 97890-816172-2-2 "That boy" by Natasha Kayser, pp.91-92

- ^ Barry: The Story of Motorcycling Legend, Barry Sheene - Steve Parrish, Nick Harris - Hachette UK, 2015 ISBN 0751560499, 9780751560497

- ^ "Ikuisesti nuori" by Arto Teronen - ISBN 978-952-6644-00-4, p.145

- ^ a b "1973 Formula 750 final classifications". Racingmemo.free.fr. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ^ a b "Formula 750 world champions". Racing Memory II.

- ^ Motorcyclist Illustrated October 1974 p.39 "Barry Sheene incidentally has two contracts. The first and most important with Suzuki Japan for Grands Prix ... and the second with Suzuki GB for British events. In the case of two clashing, Japan gets priority." Accessed 27 February 2014

- ^ a b c Kel Carruthers. "Yamaha's TZ750: Where Legends Began". superbikeplanet.com. Archived from the original on 21 December 2010.

- ^ Weeink, Frank; Burgers, Jan (2013), Continental Circus: The Races and the Places, the People and the Faces : Pictures and Stories from the Early Seventies, Mastix Press, ISBN 978-90-818639-5-7

- ^ a b "SUZUKI RG500: RG BARGY". amcn.com. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ a b c "Race of the Year". Archived from the original on 3 August 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ a b c d Barker, Stuart (2019), "Sheene and the Suzuki RG500", Classic Racer, Mortons Media Group Ltd, ISSN 1470-4463

- ^ a b Schelzig, Erik. "Daytona 200 celebrates 75th running of once-prestigious race". seattletimes.com. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ^ a b "Sheene's Horrific Daytona Fling". motorsportmagazine.com. 28 August 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gary Rose (30 August 2013). "Barry Sheene: Motorcycling's first superstar remembered". BBC Sport. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Racing Legend Barry Sheene". amcn.com.au. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ "Barry Sheene". The Times. 11 March 2003. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ a b Burgers, Jan (2018), "1975 Dutch TT", Classic Racer, Mortons Media Group Ltd, ISSN 1470-4463

- ^ "1975 Dutch TT results". motogp.com. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ a b c Burgers, Jan (2018), "Sheene Does It Again!", Classic Racer, Mortons Media Group Ltd, ISSN 1470-4463

- ^ "1975 Formula 750 final standings". Racingmemo.free.fr. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ Moses, Sam (15 March 1976). "Two flats that led to a flat-out finish". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ Assoc, American Motorcyclist (May 1976). 1976 Daytona 200, American Motorcyclist, May 1976, Vol. 30, No. 5, ISSN 0277-9358. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ^ "Teamwork's The Key" (PDF). Motor Cycle News. 2 April 1980. p. 36. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ "John Player Transatlantic Trophy". January 1979. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "Sheene conquers the world – 40 years ago today". motorsportmagazine.com. Retrieved 14 December 2023.

- ^ "1976 Nations Grand Prix results". MotoGP.com. Retrieved 14 December 2023.

- ^ Wain, Philip (2019), "John Williams: Part 2", Classic Racer, Mortons Media Group Ltd, ISSN 1470-4463

- ^ a b c "The Teammates From Hell". cyclenews.com. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ "Steve Parrish interview on Sheene". Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ^ a b Assoc, American Motorcyclist (June 1977). "Roberts, Hennen lead U.S. team past British in Match Races". American Motorcyclist. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f "135.067mph: the fastest GP of all time". motorsportmagazine.com. 20 March 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d "The Best Ever--Super Seventies". superbikeplanet.com. Archived from the original on 21 December 2010. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ a b Moses, Sam (March 1979). "The daring young man whips the heroes with ease". American Motorcyclist. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Tributes roll in for Barry Sheene". motorcyclenews.com. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ a b "Roberts: Sheene Was My Rival And Inspiration". crash.net. 13 March 2003. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ "Kenny Roberts at the Motorcycle Hall of Fame". motorcyclemuseum.org. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ Oxley, Mat (2010), An Age Of Superheroes, Haynes Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84425-583-2

- ^ Amick, Bill (1978). "Match Races: Far From Perfect But Still Neat". American Motorcyclist. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Wil Hartog Hammers Form Book". classicracer.com. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ Assoc, American Motorcyclist (November 1978). "Roberts: A Champ With Class". American Motorcyclist. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ "Roberts Declared Official Winner". The Modesto Bee. Bee News Services. 8 August 1978. p. 6. Retrieved 20 December 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Time to Fix 'Flag-to-Flag' Pit Stops Before Luck Runs Out". moto-racing.speedtv.com. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ a b Carter, Tony (2019), "Sheene Unseen", Classic Racer, Mortons Media Group Ltd, ISSN 1470-4463

- ^ a b Assoc, American Motorcyclist (July 1979). "Underdog Yanks Blitz British". Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g "An All-Time Classic: Sheene vs Roberts 40 Years On". motogp.com. 21 August 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ Sam Moses (20 August 1979). "A Thriller At Silverstone". sportsillustrated.com. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ a b "Sheene versus Roberts at Silverstone: 40 years on". motorsportmagazine.com. 20 August 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ Assoc, American Motorcyclist (September 1979). "Roberts' Suspension Lifted by the FIM". American Motorcyclist. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ Garnett, Walt (1979). "Race Watch". Cycle World. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ "Roberts Reveals Revolution Then Wins Race". motogp.com. 8 August 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ a b "The darkest day". motorsportmagazine.com. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^ "Roberts Suspended For Boycott". Modesto Bee. Modesto Bee. 2 July 1979. p. 1. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ a b c "Match Races: Part 4". Classic Racer. 18 April 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2021 – via PressReader.

- ^ "Injured Motorcyclist Leaves Intensive Care". The New York Times. August 1982.

- ^ Barker, Stuart (2003). Barry Sheene 1950–2003: The Biography. UK: CollinsWillow. p. 148. ISBN 0-00-716181-6.

- ^ "Troy Corser: One and Done". motoamerica.com. 15 July 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ "MotoGP: Seven up for Chris Vermeulen". motorcyclenews.com. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ "Barry Sheene Segrave Trophy". royalautomobileclub.co.uk. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "Brands Hatch renames curve after Sheene". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 18 March 2003.

- ^ "2016 Barry Sheene tribute ride". motogp.com. 4 September 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ Billingham, Peter (2003). Sensing the City Through Television. Intellect Books. ISBN 9781841508429. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ de Jong, Frank. "British Saloon Car Championship". History of Touring Car Racing 1952-1993. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ^ de Jong, Frank. "The European Touring Car Championship". History of Touring Car Racing 1952-1993. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- The Story so Far.

- Marriott, Andrew. The Sheene Machine.

- Scott, Michael (1983). Barry Sheene: A Will to Win. UK: Comet Books (softcover edition). p. 223. ISBN 0-86379-095-X.

- Sheene, Barry; Beacham, Ian (1983). Leader of the Pack. Queen Anne Press. p. 188. ISBN 0-356-09412-X.

- Barker, Stuart (2003). Barry Sheene 1950–2003: The Biography. UK: CollinsWillow. p. 335. ISBN 0-00-716181-6.

- Scott, Michael (2006). Barry Sheene.

- Parrish, Steve; Harris, Nick (2007). Barry.

External links

[edit]- Barry Sheene on MotoGP.com (archive)

- Barry Sheene at IMDb

- Barry Sheene profile at iomtt.com

- Interview with Stephanie McLean on her husband, Barry Sheene

- Barry Sheene's Penultimate Race article at visordown.com

- 1950 births

- 2003 deaths

- 50cc World Championship riders

- 125cc World Championship riders

- 500cc World Championship riders

- British Touring Car Championship drivers

- English motorcycle racers

- English sports broadcasters

- Deaths from cancer in Queensland

- Deaths from esophageal cancer

- Deaths from stomach cancer in Australia

- English emigrants to Australia

- Members of the Order of the British Empire

- Motorsport announcers

- People from Holborn

- Sportspeople from the London Borough of Camden

- Segrave Trophy recipients

- People from Bloomsbury

- 500cc World Riders' Champions