Judeo-Arabic dialects

A request that this article title be changed to Judeo-Arabic is under discussion. Please do not move this article until the discussion is closed. |

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (January 2024) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| Judeo-Arabic | |

|---|---|

| ערבית יהודית | |

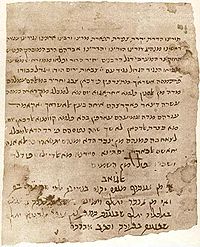

A page from the Cairo Geniza, part of which is written in the Judeo-Arabic language | |

| Ethnicity | Jews from North Africa and the Fertile Crescent |

Native speakers | 240,000 (2022)[1] |

Afro-Asiatic

| |

Early forms | |

| Hebrew alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | jrb |

| ISO 639-3 | jrb – inclusive codeIndividual codes: yhd – Judeo-Egyptian Arabicaju – Judeo-Moroccan Arabicyud – Judeo-Tripolitanian Arabicjye – Judeo-Yemeni Arabic |

| Glottolog | None |

Judeo-Arabic (Judeo-Arabic: ערביה יהודיה, romanized: ‘Arabiya Yahūdiya; Arabic: عربية يهودية, romanized: ʿArabiya Yahūdiya ; Hebrew: ערבית יהודית, romanized: ‘Aravít Yehudít ) is Arabic, in its formal and vernacular varieties, as it has been used by Jews, and refers to both written forms and spoken dialects.[2][3][4] Although Jewish use of Arabic, which predates Islam, has been in some ways distinct from its use by other religious communities, it is not a uniform linguistic entity.[2]

Varieties of Arabic formerly spoken by Jews throughout the Arab world have been, in modern times, classified as distinct ethnolects.[4] Under the ISO 639 international standard for language codes, Judeo-Arabic is classified as a macrolanguage under the code jrb, encompassing four languages: Judeo-Moroccan Arabic (aju), Judeo-Yemeni Arabic (jye), Judeo-Egyptian Arabic (yhd), and Judeo-Tripolitanian Arabic (yud).[5][4]

Many significant Jewish works, including a number of religious writings by Saadia Gaon, Maimonides and Judah Halevi, were originally written in Judeo-Arabic, as this was the primary vernacular language of their authors.

History

[edit]Jewish use of Arabic in Arabia predates Islam.[2] There were Jewish Pre-Islamic Arabic poets, such as al-Samawʾal ibn ʿĀdiyā, though surviving written records of such Jewish poets do not indicate anything that distinguishes their use of Arabic from non-Jewish use of it, and their work is thus typically excluded from considerations of Judeo-Arabic.[2] Scholars assume that Jewish communities in Arabia spoke Arabic as their vernacular language, and some claim that there is indirect evidence of the presence of Hebrew and Aramaic words in their speech, as such words appear in the Quran and might have come from contact with these Arabic-speaking Jewish communities.[2]

Before the spread of Islam, Jewish communities in Mesopotamia and Syria spoke Aramaic, while those to the West spoke Romance and Berber.[2] With the Early Muslim conquests, areas including Mesopotamia and the eastern and southern Mediterranean underwent Arabization, most rapidly in urban centers.[2] Some isolated Jewish communities continued to speak Aramaic until the 10th century, and some communities never adopted Arabic as a vernacular language at all.[2] Although urban Jewish communities were using Arabic as their spoken language, Jews kept Hebrew and Aramaic, traditional rabbinic languages, as their languages of writing during the first three centuries of Muslim rule, perhaps due to the presence of the Sura and Pumbedita yeshivas in rural areas where people spoke Aramaic.[2]

Jews in Arabic, Muslim majority countries wrote—sometimes in their dialects, sometimes in a more classical style—in a mildly adapted Hebrew alphabet rather than using the Arabic script, often including consonant dots from the Arabic alphabet to accommodate phonemes that did not exist in the Hebrew alphabet.

By around 800 CE, most Jews within the Islamic Empire (90% of the world's Jews at the time) were native speakers of Arabic like the populations around them. This led to the development of early Judeo-Arabic.[6] The language quickly became the central language of Jewish scholarship and communication, enabling Jews to participate in the greater epicenter of learning at the time, which meant that they could be active participants in secular scholarship and civilization. The widespread usage of Arabic not only unified the Jewish community located throughout the Islamic Empire but also facilitated greater communication with other ethnic and religious groups, which led to important manuscripts of polemic, like the Toledot Yeshu, being written or published in Arabic or Judeo-Arabic.[7] By the 10th century Judeo-Arabic would transition from Early to Classical Judeo-Arabic.

During the 15th century, as Jews, especially in North Africa, gradually began to identify less with Arabs, Judeo-Arabic would undergo significant changes and become Later Judeo-Arabic.[6]

Some of the most important books of medieval Jewish thought were originally written in medieval Judeo-Arabic, as were certain halakhic works and biblical commentaries. Later they were translated into medieval Hebrew so that they could be read by contemporaries elsewhere in the Jewish world, and by others who were literate in Hebrew. These include:

- Saadia Gaon's Emunoth ve-Deoth (originally كتاب الأمانات والاعتقادات), his tafsir (biblical commentary and translation) and siddur (explanatory content, not the prayers themselves)

- David ibn Merwan al-Mukkamas

- Solomon ibn Gabirol's Tikkun Middot ha-Nefesh

- Bahya ibn Paquda's Kitab al-Hidāya ilā Fara'id al-Qulūb, translated by Judah ben Saul ibn Tibbon as Chovot HaLevavot

- Judah Halevi's Kuzari

- Maimonides' Commentary on the Mishnah, Sefer Hamitzvot, The Guide for the Perplexed, and many of his letters and shorter essays.

Most communities also had a traditional translation of the Bible into Judeo-Arabic, known as a sharḥ ("explanation"): for more detail, see Bible translations into Arabic. The term sharḥ sometimes came to mean "Judeo-Arabic" in the same way that "Targum" was sometimes used to mean the Aramaic language.

Present day

[edit]In the years following the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the end of the Algerian War, and Moroccan and Tunisian independence, most Mizrahi and Sephardi Jews in Arab countries were expelled or fled, without their property, mainly for mainland France and for Israel. Judeo-Arabic was viewed negatively in Israel as all Arabic was viewed as an "enemy language".[8] Their distinct Arabic dialects in turn did not thrive in either country, and most of their descendants now speak French or Modern Hebrew almost exclusively; thus resulting in the entire group of Judeo-Arabic dialects being considered endangered languages.[citation needed] This stands in stark contrast with the historical status of Judeo-Arabic: in the early Middle Ages, speakers of Judeo-Arabic far outnumbered the speakers of Yiddish.[citation needed] There remain small populations of speakers in Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, Lebanon, Yemen, Israel and the United States.

Characteristics

[edit]The Arabic spoken by Jewish communities in the Arab world differed slightly from the Arabic of their non-Jewish neighbours. These differences were partly due to the incorporation of some words from Hebrew and other languages and partly geographical, in a way that may reflect a history of migration. For example, the Judeo-Arabic of Egypt, including in the Cairo community, resembled the dialect of Alexandria rather than that of Cairo (Blau). Similarly, Baghdad Jewish Arabic is reminiscent of the dialect of Mosul.[9] Many Jews in Arab countries were bilingual in Judeo-Arabic and the local dialect of the Muslim majority.

Like other Jewish languages and dialects, Judeo-Arabic languages contain borrowings from Hebrew and Aramaic. This feature is less marked in translations of the Bible, as the authors clearly took the view that the business of a translator is to translate.[10]

Dialects

[edit]- Judeo-Algerian

- Judeo-Egyptian

- Judeo-Moroccan

- Judeo-Tripolitanian

- Judeo-Tunisian

- Judeo-Yemeni

- Judeo-Syrian

- Judeo-Lebanese

- Modern Palestinian Judeo-Arabic

- Judeo-Iraqi

Media

[edit]Most literature in Judeo-Arabic is of a Jewish nature and is intended for readership by Jewish audiences. There was also widespread translation of Jewish texts from languages like Yiddish and Ladino into Judeo-Arabic, and translation of liturgical texts from Aramaic and Hebrew into Judeo-Arabic.[6] There is also Judeo-Arabic videos on YouTube.[6]

A collection of over 400,000 of Judeo-Arabic documents from the 6th-19th centuries was found in the Cairo Geniza.[11]

The movie Farewell Baghdad would be released in 2013 entirely in Judeo-Iraqi Arabic[12]

Orthography

[edit]Judeo-Arabic orthography uses a modified version of the Hebrew alphabet called the Judeo-Arabic script. It is written from right to left horizontally like the Hebrew script and also like the Hebrew script some letters contain final versions, used only when that letter is at the end of a word.[13] It also uses the letters alef and waw or yodh to mark long or short vowels respectively.[13] The order of the letters varies between alphabets.

| Judeo- Arabic |

Arabic | Semitic name | Transliteration |

|---|---|---|---|

| א | ا | Alef | /ʔ/ ā and sometimes ʾI |

| ב | ب | Beth | b |

| ג | ج | Gimel | g or ǧ: hard G, or J, as in get, or Jack: /ɡ/, or /dʒ/ or si in vision /ʒ/ depending on the dialect |

| גׄ, עׄ or רׄ | غ | Ghayn | ġ /ɣ/, a guttural gh sound |

| ד | د | Daleth | d |

| דׄ | ذ | Dhaleth | ḏ, an English th as in "that" /ð/ |

| ה | ه | He | h |

| ו or וו | و | Waw | w and sometimes ū |

| ז | ز | Zayn | z |

| ח | ح | Heth | ḥ /ħ/ |

| ט | ط | Teth | ṭ /tˤ/ |

| טׄ or זׄ | ظ | Theth | ẓ /ðˤ/, a retracted form of the th sound as in "that" |

| י or יי | ي | Yodh | y or ī |

| כ, ך | ك | Kaph | k |

| כׄ, ךׄ or חׄ | خ | Kheth | ḫ, a kh sound like "Bach" /x/ |

| ל | ل | Lamedh | l |

| מ | م | Mem | m |

| נ | ن | Nun | n |

| ס | س | Samekh | s |

| ע | ع | Ayn | /ʕ/ ʿa , ʿ and sometimes ʿi |

| פ, ף or פׄ, ףׄ | ف | Fe | f |

| צ, ץ | ص | Sadhe | ṣ /sˤ/, a hard s sound |

| צׄ, ץׄ | ض | Dhadhe | ḍ /dˤ/, a retracted d sound |

| ק | ق | Qof | q |

| ר | ر | Resh | r |

| ש or ש֒ | ش | Shin | š, an English sh sound /ʃ/ |

| ת | ت | Taw | t |

| תׄ or ת֒ | ث | Thaw | ṯ, an English th as in "thank" /θ/ |

| Additional letters | |||

| ﭏ | الـ | - | Definite Article "al-". Ligature of the letters א and ל |

Sample Text

[edit]| Judeo-Arabic, Iraqi variant[13] | Transliteration[13] | English[13] |

|---|---|---|

יא אבאנא אלדי פי אלסמואת, יתׄקדס אסמך, תׄאתׄי מלכותׄך, תׄכון משיתך כסא פי אלסמא ועלי אלארץ, חבזנא אלדי ללעד אעטנא אליום, ואעפר לנא מא עלינו כמא נעפר נחן לםן לנא עליה, ולא תׄדחלנא אלתׄגארב, לכן נגנא מן אלשריר, לאן לך למלך ואלקות ואלמגד אלי אלאבד

|

Yā abānā illedī fī al-samwāti, yaṯaqaddasu asmuka, ṯāṯī malakūṯuka, ṯakūnu mašyatuka kamā fī al-samā waʕalay al-ārṣi, ḥubzanāʔ al-ladī liluʕadi aʕṭinā al-yawma. Wāǧfir lanā mā ʕalaynū kamā naǧfiru naḥnu liman lanā ʕalayhi, walā ṯudḥilnāʔ al-ṯṯagāriba, lakin nagginā mina al-šširīri, lanna laka lamluka wālquqata wālmagida alay al-abdi. | Our father, which art in heaven, hallowed be thy name, thy kingdom come, thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven, give us this day our daily bread, and forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors, and lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil, for thine is the kingdom and the power and the glory for ever and ever. |

See also

[edit]- Arabic language in Israel

- Judeo-Berber language

- Judeo-Iraqi Arabic

- Baghdad Jewish Arabic

- Judeo-Moroccan Arabic

- Judeo-Tunisian Arabic

- Judeo-Yemeni Arabic

- Judeo-Syrian Arabic

- Judeo-Algerian Arabic

- Letter of the Karaite elders of Ascalon

- Arab Jews

- Haketia

- Garshuni

Endnotes

[edit]- ^ Judeo-Arabic dialects at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kahn, Geoffrey (2017-09-01). "Judeo-Arabic". In Kahn; Rubin, Aaron (eds.). Handbook of Jewish Languages (Lily ed.). BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-35954-3.

- ^ Stillman, Norman A. "Judeo-Arabic - History and Linguistic Description". Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World Online. doi:10.1163/1878-9781_ejiw_com_0012320. Retrieved 2024-10-23.

- ^ a b c Shohat, Ella (2017-02-17). "The Invention of Judeo-Arabic". Interventions. 19 (2): 153–200. doi:10.1080/1369801X.2016.1218785. ISSN 1369-801X. S2CID 151728939.

- ^ "jrb | ISO 639-3". iso639-3.sil.org. Retrieved 2022-11-13.

- ^ a b c d "Judeo-Arabic". Jewish Languages. Retrieved 2024-01-25.

- ^ Goldstein, Miriam (2021). "Jesus in Arabic, Jesus in Judeo-Arabic: The Origins of the Helene Version of the Jewish "Life of Jesus" (Toledot Yeshu)". Jewish Quarterly Review. 111 (1): 83–104. doi:10.1353/jqr.2021.0004. ISSN 1553-0604. S2CID 234166481.

- ^ Yudelson, Larry (2016-10-22). "Recovering Judeo-Arabic". jewishstandard.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved 2024-01-28.

- ^ For example, "I said" is qeltu in the speech of Baghdadi Jews and Christians, as well as in Mosul and Syria, as against Muslim Baghdadi gilit (Haim Blanc, Communal Dialects in Baghdad). This however may reflect not southward migration from Mosul on the part of the Jews, but rather the influence of Gulf Arabic on the dialect of the Muslims.

- ^ Avishur, Studies in Judaeo-Arabic Translations of the Bible.

- ^ Rustow, Marina (2020). The Lost Archive Traces of a Caliphate in a Cairo Synagogue. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 451. ISBN 978-0-691-18952-9.

- ^ "ראיון: כשבמאי ישראלי עושה סרט עיראקי". הארץ (in Hebrew). Retrieved 2024-01-25.

- ^ a b c d e "Judeo-Arabic script". www.omniglot.com. Retrieved 2024-01-28.

Bibliography

[edit]- Blanc, Haim, Communal Dialects in Baghdad: Harvard 1964

- Blau, Joshua, The Emergence and Linguistic Background of Judaeo-Arabic: OUP, last edition 1999

- Blau, Joshua, A Grammar of Mediaeval Judaeo-Arabic: Jerusalem 1980 (in Hebrew)

- Blau, Joshua, Studies in Middle Arabic and its Judaeo-Arabic variety: Jerusalem 1988 (in English)

- Blau, Joshua, Dictionary of Mediaeval Judaeo-Arabic Texts: Jerusalem 2006

- Mansour, Jacob, The Jewish Baghdadi Dialect: Studies and Texts in the Judaeo-Arabic Dialect of Baghdad: Or Yehuda 1991

- Heath, Jeffrey, Jewish and Muslim dialects of Moroccan Arabic (Routledge Curzon Arabic linguistics series): London, New York, 2002.

External links

[edit]- Alan Corré's Judeo-Arabic Literature site, via the Internet Archive

- Judeo-Arabic Literature

- Reka Kol Yisrael, a radio station broadcasting a daily program in Judeo-Moroccan Arabic

- Jewish Language Research Website Archived 2017-07-24 at the Wayback Machine (description and bibliography)

- Tafsir Rasag, a translation of the Torah into literary Judeo-Arabic, at Sefaria