Cicero, Illinois

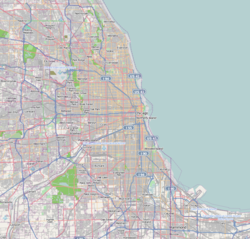

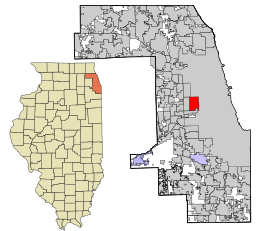

Cicero, Illinois | |

|---|---|

| |

Location of Cicero in Cook County, Illinois | |

| Coordinates: 41°50′40″N 87°45′33″W / 41.84444°N 87.75917°W[1] | |

| Country | |

| State | Illinois |

| County | Cook |

| Township | Cicero |

| Incorporated | February 28, 1867 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager |

| • President | Larry Dominick |

| Area | |

| • Total | 5.87 sq mi (15.19 km2) |

| • Land | 5.87 sq mi (15.19 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) 0% |

| Elevation | 607 ft (185 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 85,268 |

| • Density | 14,538.45/sq mi (5,613.28/km2) |

| Standard of living (2011) | |

| • Per capita income | $14,539 |

| • Median home value | $157,500 |

| ZIP Code | 60804 |

| Area code(s) | 708/464 |

| Geocode | 17-14351 |

| FIPS code | 17-14351 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2584746[1] |

| Website | www |

| [3] | |

Cicero is a town in Cook County, Illinois, United States, and a suburb of Chicago. As of the 2020 census, the population was 85,268, making it the 11th-most populous municipality in Illinois.[4] The town is named after Marcus Tullius Cicero, a Roman statesman and orator. With over 89% of the town being of Hispanic descent, the town is the most Hispanic in the state of Illinois.[5]

History

[edit]

Originally, Cicero Township occupied an area six times the size of its current territory. The cities of Oak Park and Berwyn were incorporated from portions of Cicero Township, and other portions, such as Austin, were annexed into the city of Chicago.[6]

By 1911, an aerodrome called the Cicero Flying Field had been established as the town's first aircraft facility of any type,[7] located on a roughly square plot of land about 800 meters (1/2-mile) per side, on then-open ground at 41°51′19″N 87°44′56″W / 41.85528°N 87.74889°W by the Aero Club of Illinois, founded on February 10, 1910.[8] Famous pilots like Hans-Joachim Buddecke, Lincoln Beachey, Chance M. Vought and others flew from there at various times during the "pioneer era" of aviation in the United States shortly before the nation's involvement in World War I; the field closed in mid-April 1916.[9]

After building his criminal empire in Chicago, Al Capone moved to Cicero to escape the reach of Chicago police.[10] The 1924 Cicero municipal elections were particularly violent due to gang-related efforts to secure a favorable election result.

On July 11–12, 1951, a race riot erupted in Cicero when a white mob of around 4,000 attacked and burned an apartment building at 6139 W. 19th Street that housed the African-American family of Harvey Clark Jr., a Chicago Transit Authority bus driver who had relocated to the all-white city. Governor Adlai E. Stevenson was forced to call out the Illinois National Guard. The Clarks moved away and the building had to be boarded up.[11] The Cicero riot received worldwide condemnation.[12]

Cicero was taken up and abandoned several times as site for a civil rights march in the mid-1960s. Cicero had a sundown town policy prohibiting African Americans from living in the city.[13] The American Friends Service Committee, Martin Luther King Jr., and many affiliated organizations, including churches, were conducting marches against housing and school de facto segregation and inequality in Chicago and several suburbs, but the leaders feared too violent a response in Chicago Lawn and Cicero.[14] Eventually, a substantial march (met by catcalls, flying bottles and bricks) was conducted in Chicago Lawn, but only a splinter group, led by Jesse Jackson, marched in Cicero.[15] The marches in the Chicago suburbs helped galvanize support for the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, extending federal prohibitions against discrimination to private housing. The act also created the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development's Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity, which enforces the law.

The 1980s and 1990s saw a heavy influx of Hispanic (mostly Mexican and Central American) residents to Cicero. Once considered mainly a Czech or Bohemian town, most of the European-style restaurants and shops on 22nd Street (now Cermak Road) have been replaced by Spanish-titled businesses. In addition, Cicero has a small black community.

Cicero has seen a revival in its commercial sector, with many new mini-malls and large retail stores. New condominiums are also being built in the city.

Cicero has long had a reputation of government scandal. In 2002, Republican Town President Betty Loren-Maltese was sent to federal prison in California for misappropriating $12 million in funds.[16][17] Due to this corruption, Cicero is frequently overlooked as candidate for annexation with Chicago.[18]

Geography

[edit]According to the 2021 census gazetteer files, Cicero has a total area of 5.87 square miles (15.20 km2), all land.[19] Cicero formerly ran from Harlem Avenue to Western Avenue and Pershing Road to North Avenue; however, much of this area was annexed by Chicago.

Climate

[edit]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 1,272 | — | |

| 1870 | 1,545 | 21.5% | |

| 1880 | 5,182 | 235.4% | |

| 1890 | 10,204 | 96.9% | |

| 1900 | 16,310 | 59.8% | |

| 1910 | 14,557 | −10.7% | |

| 1920 | 44,995 | 209.1% | |

| 1930 | 66,602 | 48.0% | |

| 1940 | 64,712 | −2.8% | |

| 1950 | 67,544 | 4.4% | |

| 1960 | 69,130 | 2.3% | |

| 1970 | 67,058 | −3.0% | |

| 1980 | 61,232 | −8.7% | |

| 1990 | 67,436 | 10.1% | |

| 2000 | 85,616 | 27.0% | |

| 2010 | 83,895 | −2.0% | |

| 2020 | 85,268 | 1.6% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[21] 2010[22] 2020[23] | |||

As of the 2020 census[24] there were 85,268 people, 22,698 households, and 17,508 families residing in the town. The population density was 14,538.45 inhabitants per square mile (5,613.33/km2). There were 25,836 housing units at an average density of 4,405.12 per square mile (1,700.83/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 19.22% White, 3.72% African American, 4.26% Native American, 0.59% Asian, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 46.86% from other races, and 25.30% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 89.00% of the population.

There were 22,698 households, out of which 45.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 47.83% were married couples living together, 19.60% had a female householder with no husband present, and 22.87% were non-families. 18.99% of all households were made up of individuals, and 5.63% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 4.06 and the average family size was 3.55.

The town's age distribution consisted of 28.0% under the age of 18, 12.3% from 18 to 24, 28.2% from 25 to 44, 23.2% from 45 to 64, and 8.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31.7 years. For every 100 females, there were 96.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 98.9 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $53,726, and the median income for a family was $56,632. Males had a median income of $33,835 versus $26,101 for females. The per capita income for the town was $20,040. About 11.4% of families and 13.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 18.3% of those under age 18 and 15.3% of those age 65 or over.

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[25] | Pop 2010[22] | Pop 2020[23] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 16,787 | 7,696 | 5,332 | 19.61% | 9.17% | 6.25% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 674 | 2,690 | 2,870 | 0.79% | 3.21% | 3.37% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 139 | 56 | 71 | 0.16% | 0.07% | 0.08% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 771 | 467 | 456 | 0.90% | 0.56% | 0.53% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 13 | 26 | 14 | 0.02% | 0.03% | 0.02% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 64 | 90 | 162 | 0.07% | 0.11% | 0.19% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 869 | 257 | 473 | 1.01% | 0.31% | 0.55% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 66,299 | 72,609 | 75,890 | 77.44% | 86.55% | 89.00% |

| Total | 85,616 | 83,891 | 85,268 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of 2011, 52.5% of occupied housing units were owned properties, and 47.5% were rentals. There were 4,667 vacant housing units. The average age of home properties was greater than 66 years.[26]

Cicero is a factory town. As of 1999, about a quarter of the city contained one of the greatest industrial concentrations in the world. There were more than 150 factories in 1.7 mi (2.8 km), producing communications and electronic equipment, sugar, printing presses, steel castings, tool and die makers' supplies, forging and rubber goods.[citation needed]

Arts and culture

[edit]

- St. Mary of Czestochowa, a Neo-Gothic church built in the Polish Cathedral style along with the sculpture of Christ the King by famed sculptor Professor Czesław Dźwigaj, who also cast the monumental bronze doors at St. Hyacinth's Basilica in Chicago. The church's other claim to fame is as the site of Al Capone's sister Mafalda's wedding in 1930.

- J. Sterling Morton High School, East Campus, also known as Morton East High School, was built in 1894. The original school was destroyed by fire in 1924, and the current building was constructed. Located at 2423 S. Austin Blvd, Morton East serves residents of Cicero.

- Chodl Auditorium, located inside Morton East High School, was built in 1924 (completed 1927) to replace the 1,200-seat auditorium which was destroyed by fire. The auditorium was originally a dual-purpose room, serving as a gymnasium for students, and was originally built for this purpose. In 1967 the school stopped using the auditorium as a gymnasium. Chodl Auditorium is among the largest non-commercial proscenium theatres in the Chicago Metropolitan Area and is listed with the National Register of Historic Places.

- Hawthorne Works Tower, one of the original towers of the enormous Western Electric manufacturing plant that once stood east of Cicero Avenue, is still located behind the Hawthorne Works Shopping Center near the corner of Cermak Road (22nd Street) and Cicero Avenue.

- Chicagoland Sports Hall of Fame.

On the south side of Cicero, there were two racetracks. Hawthorne Race Course, located in Cicero and Stickney, is a horse racing track still in operation. Just north of it was Chicago Motor Speedway at Sportsman's Park, which was formerly Sportsman's Park Racetrack (for horse racing) for many years. This Sportsman's Park facility is now closed, acquired by the Town of Cicero, and has since been demolished. Facilities of the Wirtz Beverage Group have been built on the west half and a Walmart built on the east half.

Government

[edit]

Most of Cicero is in Illinois's 4th congressional district; the area south of the railroad at approximately 33rd Street is in the 3rd district.[27]

The United States Postal Service operates the Cicero Post Office at 2440 South Laramie Avenue.[28]

Education

[edit]Cicero is served by Cicero Elementary School District 99 and comprises 16 schools, making it one of the largest public school districts outside of Chicago. Elementary students attend the following schools, depending on residency: Burnham (K-6), Cicero East (4-6), Cicero West (PK-4), Columbus East (4-6), Columbus West (PK-4), Drexel (K-6), Early Childhood Center (PK), Goodwin (PK-6), Liberty (K-3), Lincoln (PK-6), Roosevelt (5-6), Sherlock (PK-6), Warren Park (PK-6), Wilson (K-6), and Unity Junior High (7-8), which is separated into East/West sections. East side being held for eighth graders & seventh graders on the West side. Unity is the second largest middle school in the country. High school students entering their freshman year attend the Freshman Center and then continue high school at Morton East of the J. Sterling Morton High School District 201. The McKinley Educational Center serves as an alternative school for 5th-8th graders and the Morton Alternative School serves as an alternative school for 9th-12th graders

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago operates one PK-8 school in Cicero, Our Lady of Charity School.[29] St. Frances of Rome School closed in 2024.[30]

From 1927 until 1972, Cicero was the home of Timothy Christian School.

Cicero is also home to Morton College.

Infrastructure

[edit]

Transportation

[edit]Cicero is served by two major railroad lines, the BNSF Railway and the Belt Line Railroad. Public Transportation is provided by Metra's BNSF Line between Aurora and Chicago's Union Station with a stop at the Cicero station near Cicero Avenue and 26th Street. Currently, this station is undergoing a much needed reconstruction and expansion by Metra. Also, the CTA Pink Line provides daily service from the 54th/Cermak terminal to the Loop. Its Cicero station is also located in Cicero. Multiple Pace and CTA bus routes cover portions of Cicero.

Fire department

[edit]The Cicero Fire Department (CFD) has a staff of 97 professional full time firefighters. The CFD operates out of three fire stations.[31]

Notable people

[edit]- Felix Biestek (1912–1994), American priest and professor

- Al Capone (1899–1947), American gangster and businessman and the co-founder and boss of the Chicago Outfit.

- JoBe Cerny (born 1947), an actor from Cicero, is the voice of the Pillsbury Doughboy.

- Joe Mantegna (born 1947), Tony award-winning actor, also writer and director.

- Erika Sánchez (born 1983/1984), American poet and writer

- Lee Corso (born 1935), Former football coach and media personality.

- Donald F. White (1908–2002), Canadian-born American architect and engineer, of African descent[32]

In popular culture

[edit]- In the HBO series Boardwalk Empire, Cicero is the home of Al Capone. Many of the episode plots are based in Cicero.

- Cicero is mentioned as the hometown of Jimmy McGill/Saul Goodman and his brother Chuck McGill in Better Call Saul.

- In the musical Chicago, Velma Kelly mentions Cicero in the number "Cell Block Tango" as the location of the hotel where she murdered her husband Charlie and sister Veronica.

- In Walker Percy's novel Love in the Ruins, the schismatic American Catholic church establishes Cicero, Illinois as its "new Rome."

- In Bertolt Brecht's The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, Cicero is annexed by Chicago as a satirical allegory for the Nazi annexation of Austria.

- In Guys and Dolls, the Chicago-area gangster "Big Julie" claims to be from "East Cicero, Illinois" (and pronounces the final "s" on Illinois).

- In the 1948 film noir Sorry, Wrong Number, the story takes place in New York City but in flash-backs recounted by several characters we learn that the story actually begins in Chicago and Cicero. The female character Leona Cotterel (Barbara Stanwyck) is the rich, spoiled daughter of the owner of a pharmaceutical company located in Cicero. She lives with her father in a Chicago mansion. A few years later, after she marries, the story moves to Bayonne, New Jersey, and ends in Manhattan and Staten Island.

- Al Bundy from the show Married... with Children mentions that he gets his hair cut in Cicero.

- In the song "Guns Under the Counter" by The Fiery Furnaces (from their album Rehearsing My Choir), Cicero is mentioned in the line "In Cicero, Never stand at a window".

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Cicero, Illinois

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 15, 2022. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ Illinois Regional Archives Depository System. "Name Index to Illinois Local Governments". Illinois State Archives. Illinois Secretary of State. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ "Cicero town, Illinois". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 14, 2022. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ^ "State's Hispanic population now fifth in nation | Journal-Courier".

- ^ "Cicero, IL". Encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org. Archived from the original on November 27, 2012. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

- ^ Gray, Carroll (2005). "CICERO FLYING FIELD - Origin, Operation, Obscurity and Legacy - 1891 to 1916 - OPERATION, 1911 - THE ESTABLISHMENT OF CICERO FLYING FIELD". lincolnbeachey.com. Carroll F. Gray. Archived from the original on May 9, 2017. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

The second great aeronautical event of 1911 around Chicago was the establishment by the A.C.I. of a top-notch flying field named 'Cicero Flying Field' (or simply 'Cicero') within the township limits of Cicero (bounded by 16th St., 52nd Ave., 22nd St. and 48th Avenue. At some point during May, the A.C.I. was given a five year lease on the Cicero property by the Grant Land Association, Harold F. McCormick's property holding company. At the conclusion of the 1911 Aviation Meet, the hangars in Grant Park were moved to the southern edge of the 2-1/2 sq. mi. lot in Cicero.

- ^ Gray, Carroll (2005). "CICERO FLYING FIELD - Origin, Operation, Obscurity and Legacy - 1891 to 1916 - 1909 & 1910 - GLENN H. CURTISS & THE AERO CLUB OF ILLINOIS". lincolnbeachey.com. Carroll F. Gray. Archived from the original on May 9, 2017. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

The day before his two-day exhibition flights at the Hawthorne Race Track in Cicero, Illinois, on October 16 and 17, 1909, Glenn Curtiss spoke to the Chicago Automobile Club and suggested that an aero club be formed in Chicago. In response to his remarks, the Aero Club of Illinois ('A.C.I.') was incorporated on February 10, 1910, with Octave Chanute as its first president—a perfect choice, to be sure... The second great aeronautical event of 1911 around Chicago was the establishment by the A.C.I. of a top-notch flying field named 'Cicero Flying Field' (or simply 'Cicero') within the township limits of Cicero (bounded by [West] 16th St., 52nd Ave [S. Laramie Avenue]., 22nd St [West Cermak Road]. and 48th Ave.), conveniently located adjacent to interurban rail service—just a 15 min. 5¢ trip on the Douglas Park 'L' from downtown Chicago, and also was served by two streetcar lines.

- ^ Gray, Carroll (2005). "CICERO FLYING FIELD - Origin, Operation, Obscurity and Legacy - 1891 to 1916 - 1916 - THE FINAL FLIGHT & A NEW FIELD". lincolnbeachey.com. Carroll F. Gray. Archived from the original on May 9, 2017. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

On April 16, 1916, when 'Matty' Laird took off from Cicero Flying Field, at the controls of his self-designed and self-built Boneshaker biplane and flew to the new Partridge & Keller aviation field at 87th St. and Pulaski Road, in Chicago, Cicero Flying Field ceased to be. The next day, the Aero Club of Illinois (A.C.I.) officially opened its new 640 acre Ashburn Field on land purchased by A.C.I. President 'Pop' Dickinson for the A.C.I. Ashburn was located at 83rd St. and Cicero Avenue, about 7-1/2 miles almost due south of Cicero. All of the hangars and buildings at Cicero had been moved to Ashburn Field some months earlier.

- ^ Duechler, Doug (September 5, 2006). "Part II: From Capone to 'Bohemian Wall Street' to, of course, Betty". News. Wednesday Journal of Oak Park and River Forest. Colorful Cicero. Oak Park, Illinois: Wednesday Journal. LCCN sn91055447. OCLC 24273230. Archived from the original on January 19, 2021. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ^ "1951 Race Riots Then & Now - Cicero, IL". Archived from the original on November 28, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- ^ Wilkerson, Isabel (2020). The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great Migration. New York: Random House. p. 375. ISBN 978-0-679-44432-9.

- ^ Nolte, Robert (September 8, 1966). "'Victory' Means Little to Cicero". Billings Gazette. Billings, Montana. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

Although he says the Cicero march was a victory, residents of Cicero probably feel no different about Negroes than they did one week ago. (Negroes are not allowed to live in Cicero, but ironically, 15,000 of them work in the suburb's factories and stores five days a week.)

- ^ "Chicago Lawn". Encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org. Archived from the original on August 10, 2012. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

- ^ "American Experience.Eyes on the Prize.The Story of the Movement". PBS. Archived from the original on January 31, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

- ^ Engel, Matthew (August 31, 2002). "Spirit of Capone lives on in Mobtown, Illinois". The Guardian. Cicero, Illinois. Retrieved April 10, 2011.

- ^ "Betty Loren-Maltese and fellow perps". Ipsn.org. June 16, 2001. Archived from the original on August 22, 2012. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

- ^ McClelland, Edward. "Won't You Be My (Annexed) Neighbor?". Chicago Magazine. Retrieved November 9, 2024.

- ^ "Gazetteer Files". Census.gov. Archived from the original on August 24, 2019. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- ^ "NASA Earth Observations Data Set Index". NASA. Archived from the original on May 10, 2020. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ "Decennial Census of Population and Housing by Decades". US Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022.

- ^ a b "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Cicero town, Illinois". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on October 12, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ a b "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Cicero town, Illinois". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on October 12, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Cicero city, Illinois". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "Selected Housing Characteristics: 2011 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates (DP03): Cicero town, Illinois". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ "Welcome to The Town of Cicero". Thetownofcicero.com. Archived from the original on November 25, 2012. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

- ^ "Post Office Location - CICERO Archived 2012-07-20 at archive.today." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on April 17, 2009.

- ^ "Welcome To Our Lady of Charity School in Cicero, Illinois". Olc-school.org. November 13, 2012. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

- ^ ""Archdiocese of Chicago announces closure of two west suburban Catholic schools" Archived February 8, 2024, at the Wayback Machine." WGN News. Retrieved on February 8, 2024.

- ^ Fire Department Archived February 6, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Thetownofcicero.com. Retrieved on July 21, 2013.

- ^ Wilson, Dreck Spurlock (March 2004). "Donald Frank White (1908–2002)". African American Architects: A Biographical Dictionary, 1865-1945. Routledge. pp. 600–604. ISBN 978-1-135-95629-5.